Author: Julián Monge Nájera, Ecologist and Photographer

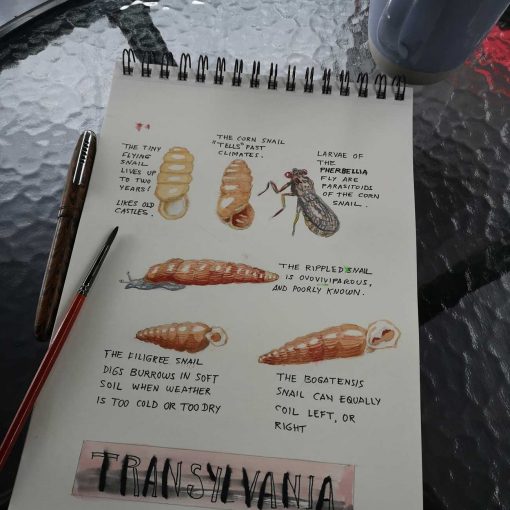

I can imagine how, over 150 years ago, Emma Darwin showed her usual patience and love when her husband Charles began to submerge land snails in seawater. What was Charles trying to do? Actually, he was trying to solve one of the great mysteries of nature, how the slow and fragile land snails appear in the midst of the deadliest deserts, and on distant islands that were never connected to a continent.

Charles Lyell, whose geology book was instrumental in Darwin discovering how species evolve, suggested that land snails could only have reached unexplained places by being carried by sea or by birds. But it was just an idea, there was no evidence to support it. Like any good scientist, Darwin did experiments in which his loving and patient wife helped, just like she played the piano for him to find out if earthworms could hear (Emma studied piano with none other than Frédéric Chopin!).

With the snail experiments, Darwin found that Helix pomatia snails survived 20 days in seawater; thus, they could travel long distances in the floating vegetation that rivers carry to sea during storms, and then start new populations in new lands¹.

But Darwin’s experiment did not prove that snails survived the sea voyage on floating debris, only that it could happen. However, in 2011, Polish scientists collected vegetation brought to the beach by a storm in the Baltic Sea, and they found several safe and healthy Cepaea nemoralis snails; these snails continue to lay fertilized eggs for more than a year after mating, so one is enough to establish an entire new population².

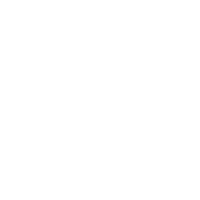

But an even more incredible way that land snails use to travel is flying, attached to insects. Of course, we would not believe this, were it not because there are a dozen cases confirmed by science. For example, tiny Pomatias elegans travels by air attached to bumblebee legs³.

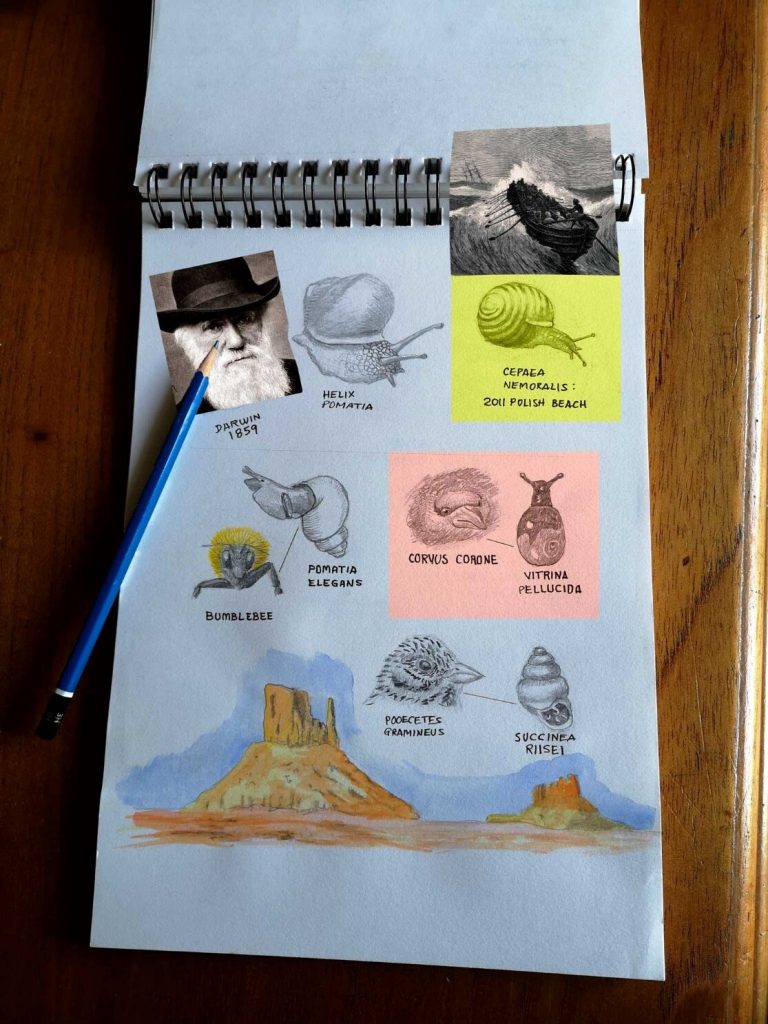

The small snail Vitrina pellucida occasionally appears in the plumage of migratory birds, which carry up to 10 snails each, for example in the carrion crow, Corvus corone, which travels from north to south and vice versa within Eurasia. There are even more spectacular cases, such as the Puerto Rican snail Succinea riiseifound in the Arizona desert traveling over a sparrow (Pooecetes gramineus). An even more spectacular case: eggs of Succinea snails have been found in the middle of the Sahara desert, attached to migratory birds that travel between Africa and Europe³.

In addition to long flights in migratory birds, land snails can be carried short distances by birds that collect vegetation for their nests, for example, caracoles Fruticicola fruticum, and Zonitoides nitidus⁴.

The snail Cochlicopa lubrica has been found in Europe in eagle nests (Aquila pomarina). In nests, snails not only find a new place to colonize, but also a suitable microclimate and abundant food⁵.

Another way to «fly» is being carried away by the stormy wind, and even if the trip is only a few meters long, they can cross, for example, small water causes that would otherwise be a barrier. This was discovered in Hawaii by placing transceptors on two foliage snail species, Achatinella mustelina, and Achatinella sowerbyana⁶.

Experiments made in the 90s showed that snails that are very small, either because they are young or because the species is small, such as Truncatellina rothi, can travel kilometers over land and sea carried by strong storms winds⁷.

Equally surprising is the case of the Vallonia, small land snails that live in vegetation next to the water: their fossils show that at least in the latest 5 million years, their geographic ranges always match those of certain fishes. They are land snails, but it seems that fish accidentally swallow them when they eat vegetation from the shore. Snails survive passage through the digestive system and travel long distances upstream. Fish and snails are closely associated, and with their habitats disappearing, both are becoming extinct⁸.

It is possible that we are the main dispersers of land snails, and we do it by moving soil, plants, fish, and equipment worldwide. I already mentioned in this series how some snails traveled with the Roman army and, more recently, with the US Army. But there are other ways, green roofs are becoming more and more fashionable, and thanks to them, thousands of species find habitat on houses and buildings. Among them, snails that are rare or even extinct in some areas.

Apparently, the first to report this was the Finns, who found four species on green roofs: Cochlicopa lubrica, Oxyloma elegans, Pseudotrichia rubiginosa, and Succinella oblonga⁹. These snails are transported in the vegetation and soil used to build green roofs. Did you notice the cover photo of Darwin, then a child, holding a pot that almost certainly contained many invisible invertebrate eggs?

Wind, water, and other animals, from the “not so surprising” birds to the implausible fish and insects, are the «travel agencies» that explain the incredible ability of one of the slowest animals ever to travel all over the world. And they, in some way, do the same for others: a recent study found that snails are dispersers of many nematodes, which survive the digestive system of these mollusks, just like they survive going through the digestive tracts of fish and birds¹⁰.

*Edited by Zaidett Barrientos, Katherine Bonilla y Carolina Seas.

Originally published in Blog Biología Tropical: 18 august 2020

REFERENCES

¹ Darwin, C. (1859). On the origin of species by means of natural selection. London, England: John Murray.

² Ożgo, M., et al. (2016). Dispersal of land snails by sea storms. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 82(2), 341–343.

³ Rees, W. J. (1965). The aerial dispersal of Mollusca. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 36(5), 269-282.

⁴ Shikov, E. V., & Vinogradov, A. A. (2013). Dispersal of terrestrial gastropods by birds during the nesting period. Folia Malacologica, 21(2), 105-110.

⁵ Maciorowski, G., et al. (2012). An example of passive dispersal of land snails by birds-short note. Folia Malacologica, 20(2), 139-141.

⁶ Hall, K. T., & Hadfield, M. G. (2009). Application of harmonic radar technology to monitor tree snail dispersal. Invertebrate Biology, 128(1), 9-15.

⁷ Kirchner, C. H., et al. (1997). Flying snails—how far can Truncatellina (Pulmonata: Vertiginidae) be blown over the sea?. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 63(4), 479-487.

⁸ Altaba, C. R. (2015). Once a land of big wild rivers: specialism is context-dependent for riparian snails (Pulmonata: Valloniidae) in central Europe. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 115(4), 826-841.

⁹ Páll-Gergely, B., et al. (2014). Green roofs provide habitat for the rare snail (Mollusca, Gastropoda) species Pseudotrichia rubiginosa and Succinella oblonga in Finland. Memoranda Societatis pro Fauna et Flora Fennica, 90, 13–15.

¹⁰ Sudhaus, W. (2018). Dispersion of nematodes (Rhabditida) in the guts of slugs and snails. Soil Organisms, 90(3), 101-114.