Author: Julián Monge Nájera, Ecologist and Photographer

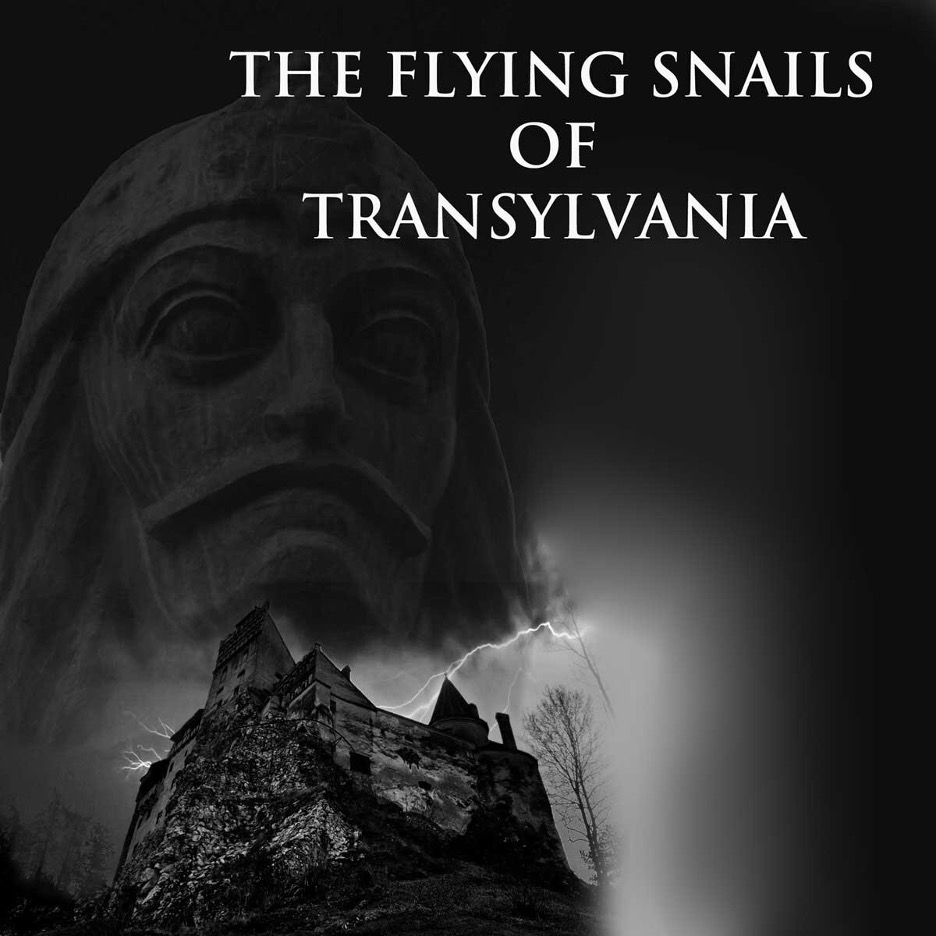

In his 1897 novel Dracula, Bram Stoker used Transylvanian nature as background, but besides the wolves, he did not turn animals into characters for his novel. This led me to inquire about what kind of land snails inhabit the Carpathian forest that so much scared Jonathan Harker in the land of Vlad Dracula.

In Dracula, Bram Stoker commented that the Transylvanian landscape was among the last unknown regions left in Europe; but, luckily, if you want to learn about Transylvanian land snails, there is a recent study about the snails of Cheile Vârghișului, one of the snail rich limestone areas of the Carpathians¹ .

And the report is surprising; I expected some monster snails fit to keep company with vampires, but no, the snails are tiny, many are endangered, and in some cases, we only know that they exist and little else.

The Carpathian forest is abundant in the common beech (Fagus sylvatica); home to wolves, bears, boars and roe deer, and scary at night:

“Then, far off in the distance, from the mountains on each side of us began a louder and a sharper howling—that of wolves—which affected both the horses and myself in the same way—for I was minded to jump from the calèche and run, whilst they reared again and plunged madly, so that the driver had to use all his great strength to keep them from bolting”².

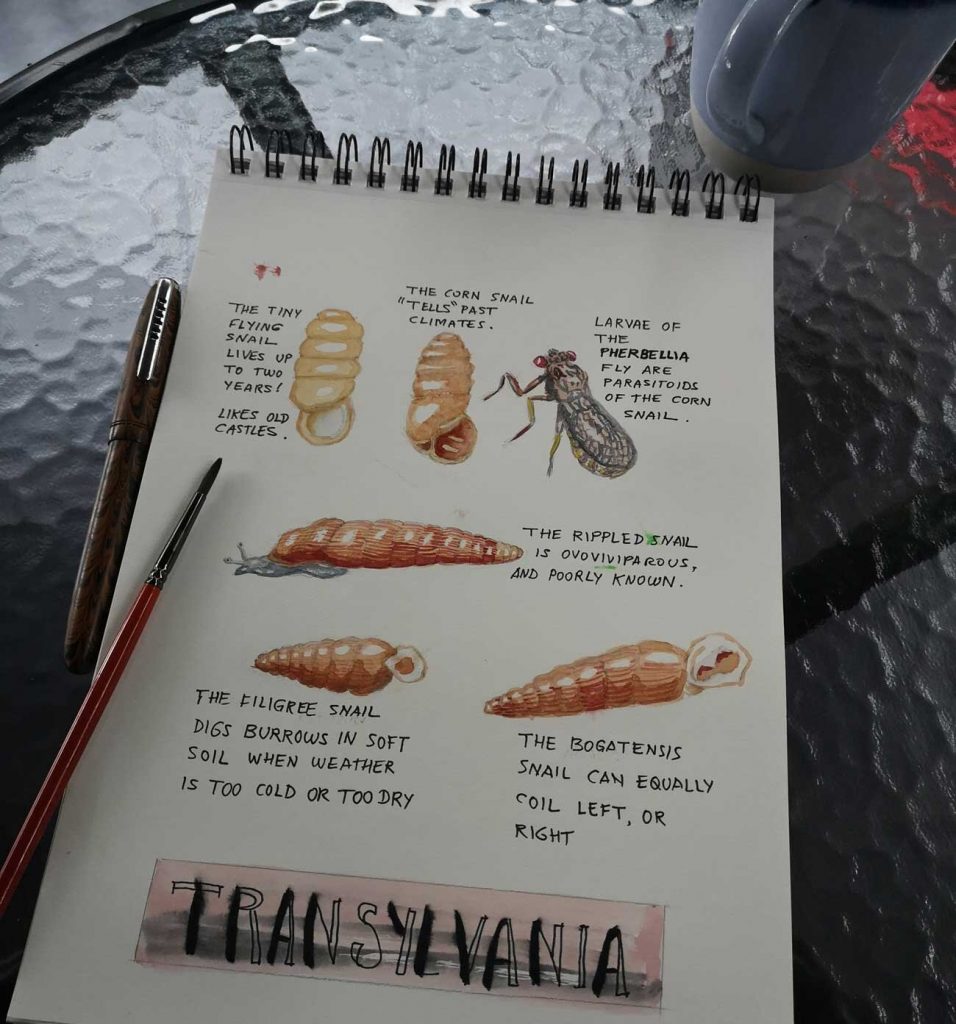

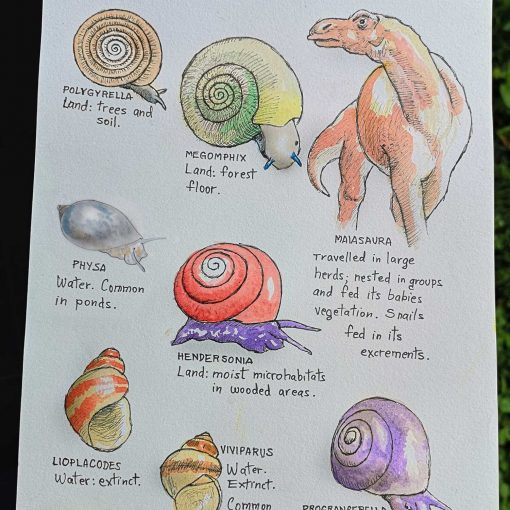

The limestone habitats, which from a distance look like giant skulls, have large populations of tiny snails, like the cylinder snail (Truncatellina cylindrica) and the corn snail (Granaria frumentum). The greener parts are dominated by the so-called door snails or clausiliids, mostly the rippled snail (Laciniaria plicata), the filigree snail (Ruthenica filograna) and the bogatense snail (Alopia bogatensis). Here are some watercolor sketches I made to give you an idea of what these snails look like:

The cylinder snail, Truncatellina cylindrica

Let us start with the cylinder snail (Truncatellina cylindrica); unlike the other species from this forest, we know a bit about this snail, humorously called by Prof. Kirchner and colleagues “the flying snail” for the reason we will soon see.

The 2 mm long shell is a beautiful golden brown, and its growth interruptions are a hint that the animal survives the winter but stops growing during that difficult season.

It is found in sunny areas, and curiously, this snail used the stonecrop plant (Sedum) as a roof, thousands of years before these particular plants became common in our own green roofs (sempergreen.com).

In the second half of the year, the snail lays up to 11 eggs, smaller than a ball-pen dot, which surprisingly is protected by calcium like the eggs of vertebrates. After three weeks, the eggs hatch, and the snails live a maximum of 2 years. Snails of this size are thought to be transported by the wind over long distances, even over the sea, and that is why they have been called “flying snails”³.

The cylinder snail can become common in abandoned castles, but suffer when the castles are restored and they lose their microhabitats⁴.

The corn snail, Granaria frumentum

The second snail in our list, the 8 mm long corn snail, Granaria frumentum, grows better in the northern slope of hills, just like its relatives in the Fortress of Saladin (see the Saladin article from this series here)⁵.

Nobody knows why for this particular species, but it may be that the northern side is moister and thus, richer in food and less demanding physiologically.

The effect of climate on shell size is used to estimate the temperature in archaeological and fossil sites where the snail remains are found⁶.

The poor snail is the sole victim of larvae of the parasitoid fly Pherbellia limbate⁷.

The rippled snail, Laciniaria plicata

At 4 cm long, the rippled snail Laciniaria plicata is a giant among door snails, which are normally under 1 cm long; little is known about its biology, but quite curiously it has been found attached to frogs⁸.

Other than that, I could find almost nothing about the rippled snail of Transylvania.

The filigree snail, Ruthenica filograna

The filigree snail, Ruthenica filograna, is 9 mm long, pale yellowish brown, and curiously the shape of its aperture changes greatly from region to region, but nobody knows if this is an adaptation for local conditions or a random mutation⁹.

Unlike the fictional vampires, it seems to do well in sunny spots and can dig itself into the soil when cool and dry weather make it necessary. Filigree snails become adults in 3-6 months¹⁰.

They like to live in a litter of hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) and ash (Fraxinus excelsior), but avoid the litter of oak (Quercus), sycamore (Acer pseudo-platanus) and aspen (Populus tremula), which may be unedible to them¹¹.

The bogatensis snail, Alopia bogatensis

The bogatensis snail, Alopia bogatensis, is horny yellowish, intermediate in size (19 mm) and seems to prefer humid limestone habitats in mountains. Where it occurs, it dominates other snails and reaches large densities¹.

Unlike most land snails, members of the Clausiliidae family are almost exclusively sinistral. And in the case of the genus Alopia to which bogatensis belongs, both sinistral and dextral species are known, but they seem to appear at random. Again, nobody knows why a direction for growth has not been fixed in these mysterious animals¹².

Will the Carpathian snails disappear soon into the darkness of the Transylvanian night?

The Carpathian snails are threatened by continuous habitat destruction, and in some cases, they represent the last populations of species now extinct in other parts of Europe. Their survival depends on the persistence of limestone habitats with good moisture and vegetation, or, for other species, on the availability of forest with appropriate litter1. Let us hope they stay with us for many years to come.

I can only wonder if, at any time in his life, perhaps as a child, Vlad Dracula took a moment to observe any of these snails that inhabited his beautiful but suffering land.

*Edited by Zaidett Barrientos, Katherine Bonilla y Carolina Seas.

Originally published in Blog Biología Tropical: 21 august 2020

REFERENCES

¹ Gheoca, V. (2016). Land snail communities of Cheile Vârghișului Nature Reserve (the Perșani Mountains, Romania). Studia Universitatis Babeş-Bolyai Biologia, 61(2), 167-176.

² Stoker, B. (1897). Dracula. New York, USA: Grosset and Dunlap.

³ Kirchner, C. H., Krätzner, R., & Welter-Schultes, F. W. (1997). Flying snails—how far can Truncatellina(Pulmonata: Vertiginidae) be blown over the sea? Journal of Molluscan Studies, 63(4), 479-487.

⁴ Alexandrowicz, W. P. (2013). The malacofauna of the castle ruins in Melsztyn near Tarnow (Roznow Foothills, Southern Poland). Folia Malacologica, 21(1), 9-18.

⁵ Gittenberger E. (1973). Beitrage zur Kenntniss der Pupillacea. III. Chondrininae. Leiden, 127, 1-266.

⁶ Sólymos, P., & Sümegi, P. (1997). The shell morpho-thermometer method and its application in palaeoclimatic reconstruction. Annales Universitatis Scientiarum Budapestinensis de Rolando Eotvos Nominatae, Sectio Geologica, 32, 137-148.

⁷ Nerudova-Horsakova, J., et al. (2016). Biology and immature stages of Pherbellia limbata (Diptera: Sciomyzidae), a parasitoid of the terrestrial snail Granaria frumentum. Zootaxa, 4117(1), 048-062.

⁸ Kolenda, K., et al. (2017). A possible phoretic relationship between snails and amphibians. Folia Malacologica, 25(4), 281-285.

⁹ Szybiak, K., & Leśniewska, M. (2008) Variability in the sculpture of the shell aperture of Ruthenica filograna (Rossmässler, 1836) (Gastropoda: Clausiliidae) in specimens from natural populations and from laboratory breeding. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 74 (2), 183-189.

¹⁰ Szybiak, K., et al. (2015). Reproduction and shell growth in two clausillids with different reproductive strategies. Biologia, 70(5), 625-631.

¹¹ Szybiak, K., et al. (2009). Variation in spatial structure and abundance of clausiliids (Mollusca: Clausiliidae) in the nature reserve Debno nad Wartą (W Poland) during wintering. J. Conch, 39(6), 611-620.

¹² Fehér, Z., et al. (2013). Molecular phylogeny of the land snail genus Alopia (Gastropoda: Clausiliidae) reveals multiple inversions of chirality. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 167(2), 259-272.

Una idea sobre “The flying snails of Transylvania that shared the land with the real Dracula”

Hey just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your article seem to be running off the

screen in Internet explorer. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to

do with web browser compatibility but I figured I’d

post to let you know. The design look great though! Hope you get the problem

resolved soon. Cheers