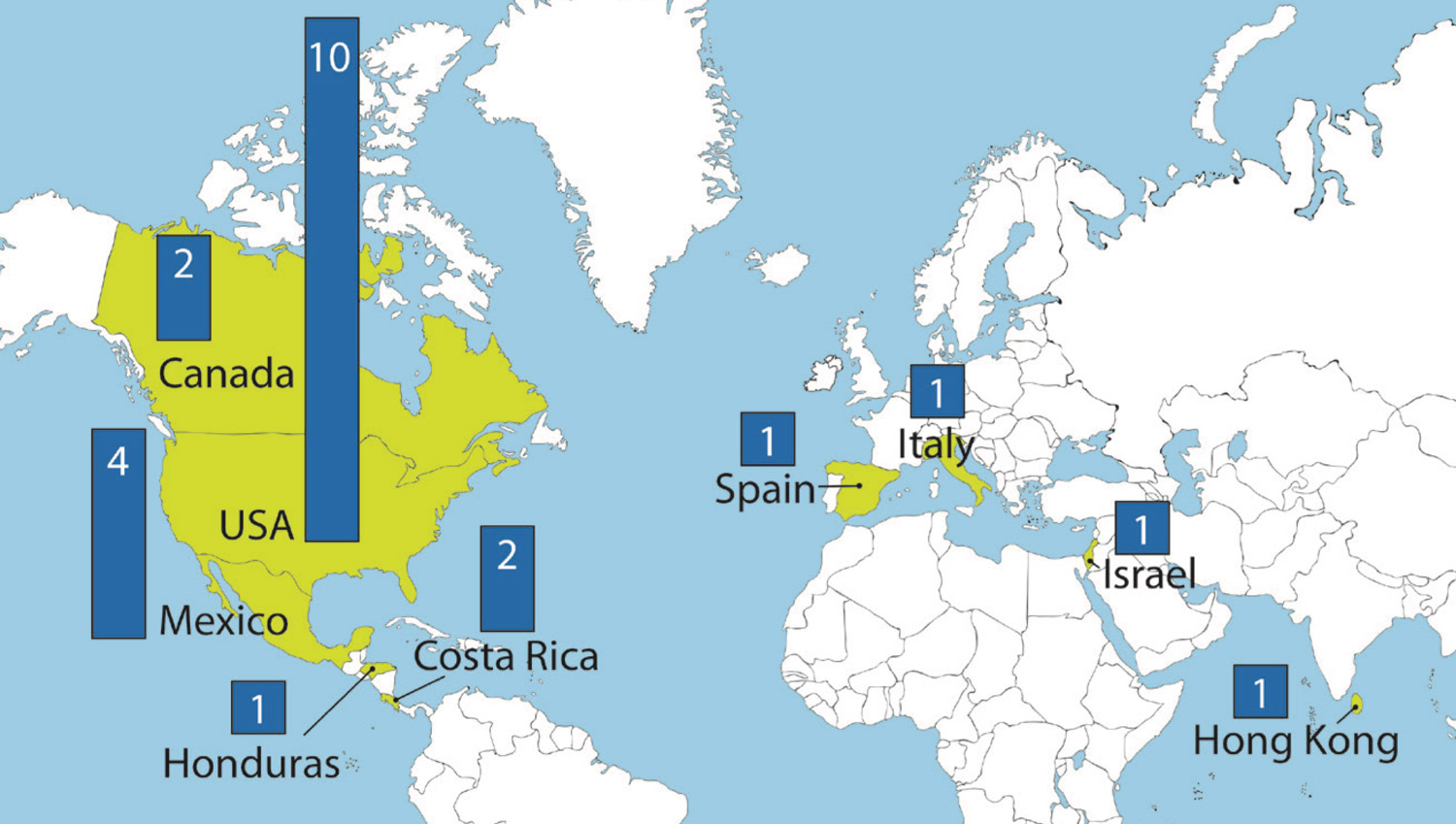

Author: Julián Monge Nájera, Ecologist and Photographer

The cloud forest of Costa Rica is home to an extraordinary snail, with a behavior sometimes reminiscent of bats, sometimes of domestic cats. Its survival seems likely thanks to the hydroelectric production program of Costa Rica, one of the world’s most advanced countries in carbon neutrality.

Snails do not have dry skin to protect them from dehydration, and they need abundant water to produce the jelly-like substance on which they glide. They do everything to conserve humidity: their shells are usually light-colored and therefore reflect more heat; in addition, shells prevent the passage of water; snails prefer to be active at night or when the humidity is high after rain, and if necessary, they seal their shell, either with a calcareous lid (operculum) or with a temporary membrane (epiphragm). Their relatives, slugs, can even produce a mucous cocoon that they reinforce with moss and dirt.

The snail Tikoconus costarricanus has an additional technique to conserve valuable moisture. Costa Rican biologist Zaidett Barrientos studied it in the Río Macho Forest Reserve (maintained as aquifer security by the Costa Rican Electricity Institute) and observed something that no one had seen: the snail was hanging like a bat¹.

After years of work, she was able to understand what was happening: when the humidity drops at a certain time of day, the snail begins to contract, covers its tentacles in “raises” the front of its foot from the ground (in this case, the «ground» is the lower part of the leaf to which it is attached). Barely hanging from the back of the foot, the snails wraps itself in its mantle as a person would with a blanket on a cold night. Then, it enters a state of inactivity in which only its breath is noticed, and it remains immobile until humidity increases, generally a few hours later¹.

To become active again, it follows the opposite sequence, I suppose because snails do not tend to complicate themselves unnecessarily: after all, they have always been seen by humans as an example of patience and tranquility.

If you want to see this incredible behavior, the article includes several videos! https://revistas.uned.ac.cr/index.php/cuadernos/article/view/2802

From the point of view of these snails, their enemies can be huge, small like themselves, or invisible. We know almost nothing about the enemies of Tikoconus costarricanus, but they probably include large species, like birds and lizards, which eat them; small ones, such as parasitoid flies and planarians, which could also eat them; and invisible enemies, like flukes, nematodes, and parasitic protozoa, which could make them sick. All this remains to be studied.

How sad would it would be to see an enemy approach you and not be able to escape quickly! And this should be the case for snails, but not for Tikoconus costarricanus, this species can disappear at spectacular speed!

As Barrientos discovered, in the event of danger, the snail contorts violently, detaching itself from the leaf and instantly falling to the forest floor, where it is hidden somewhere in the dense litter where it is almost impossible to find it¹.

And why did I say that it reminds us of cats, too?

Because Tikoconus costarricanus cleans itself with its tongue, just like cats do. This surely protects it from fungi and bacteria, just as showers protects us from many skin pathogens1. Maybe other snails do it too, but, until the present, no one cared to study and publish it, so we must thank this Costa Rican biologist for reporting this grooming behavior. How many more surprising secrets does this little tropical mollusk keep?

*Edited by Katherine Bonilla y Carolina Seas.

Originally published in Blog Biología Tropical: 20 august 2020

REFERENCES

¹ Barrientos, Z. (2020). A new aestivation strategy for land molluscs: hanging upside down like bats. UNED Research Journal, 12(1), e2802-e2802.

788 ideas sobre “The surprising “bat snail” of Costa Rica”

Hello there! This article couldnít be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my previous roommate! He continually kept preaching about this. I will send this information to him. Fairly certain he’ll have a great read. Many thanks for sharing!

http://amoxil.icu/# over the counter amoxicillin

where can i buy generic clomid without dr prescription cost cheap clomid no prescription – get cheap clomid

http://zithromaxbestprice.icu/# zithromax 250 mg australia

tamoxifen hormone therapy: tamoxifen adverse effects – tamoxifen for sale

http://canadianpharm.store/# canada discount pharmacy canadianpharm.store

top 10 online pharmacy in india: Indian pharmacy to USA – best india pharmacy indianpharm.store

mexican rx online Online Pharmacies in Mexico mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexicanpharm.shop

https://canadianpharm.store/# northern pharmacy canada canadianpharm.store

purple pharmacy mexico price list: Certified Pharmacy from Mexico – purple pharmacy mexico price list mexicanpharm.shop

http://indianpharm.store/# indianpharmacy com indianpharm.store

purple pharmacy mexico price list: Certified Pharmacy from Mexico – buying prescription drugs in mexico mexicanpharm.shop

http://canadianpharm.store/# ed drugs online from canada canadianpharm.store

Online medicine order: Indian pharmacy to USA – buy medicines online in india indianpharm.store

india online pharmacy international medicine delivery from india indian pharmacy paypal indianpharm.store

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexico drug stores pharmacies – buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

https://mexicanpharm.shop/# reputable mexican pharmacies online mexicanpharm.shop

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs Certified Pharmacy from Mexico mexican drugstore online mexicanpharm.shop

world pharmacy india: order medicine from india to usa – indian pharmacy paypal indianpharm.store

https://canadianpharm.store/# best canadian online pharmacy canadianpharm.store

mexico drug stores pharmacies Online Pharmacies in Mexico buying prescription drugs in mexico mexicanpharm.shop

top online pharmacy india: india pharmacy – Online medicine home delivery indianpharm.store

http://canadianpharm.store/# canadian neighbor pharmacy canadianpharm.store

purple pharmacy mexico price list: Online Pharmacies in Mexico – mexican mail order pharmacies mexicanpharm.shop

canadian pharmacy online store Canadian Pharmacy canadian mail order pharmacy canadianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm.shop/# mexican drugstore online mexicanpharm.shop

pharmacies in canada that ship to the us: Canadian International Pharmacy – recommended canadian pharmacies canadianpharm.store

Online medicine home delivery order medicine from india to usa buy prescription drugs from india indianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm.shop/# buying prescription drugs in mexico mexicanpharm.shop

https://canadadrugs.pro/# non prescription

largest canadian pharmacy buying prescription drugs canada canadian prescription drugstore

prescription drug prices comparison: canadian drug store – best canadian online pharmacy reviews

https://canadadrugs.pro/# canadian pharmacies without prescriptions

trustworthy canadian pharmacy canadian prescriptions cheap canadian pharmacy

best online canadian pharmacy: canadian prescriptions – discount prescription drugs

https://canadadrugs.pro/# no prescription needed canadian pharmacy

canadian mail order pharmacy northwest canadian pharmacy cheapest canadian pharmacy

canadian pharmacy rx: discount online canadian pharmacy – trusted canadian pharmacy

http://canadadrugs.pro/# canadian drug mart pharmacy

canadian family pharmacy online pharmacies no prescription required pain medication mail order pharmacy

trusted online pharmacy: drugs online – canadian pharmacy 365

https://canadadrugs.pro/# viagra mexican pharmacy

pharcharmy online no script: canadian pharmacy canada – mexican pharmacies online cheap

list of aarp approved pharmacies cheap prescription drugs canada drug store

https://canadadrugs.pro/# canadian pharmacy no rx

northwest canadian pharmacy: overseas pharmacies – online medication

https://canadadrugs.pro/# buy prescription drugs canada

best online canadian pharcharmy: buy prescription drugs without doctor – best canadian drugstore

canadian drugs: mexican pharmacies online – drugs without a prescription

https://canadadrugs.pro/# world pharmacy

mail order drugs without a prescription: mexican pharmacy online – prescription drugs canada

http://canadadrugs.pro/# canada pharmacy no prescription

northwestpharmacy: medications canada – drugs canada

https://canadadrugs.pro/# legitimate canadian pharmacy online

http://canadadrugs.pro/# meds canadian compounding pharmacy

medicin without prescription: canada pharmacy online – non prescription canadian pharmacy

cheap canadian drugs pain meds online without doctor prescription canadian drug companies

https://edpill.cheap/# ed drugs list

canadianpharmacyworld canadian medications canadian pharmacies

canadian pharmacy uk delivery: legit canadian online pharmacy – canadian pharmacy phone number

http://edpill.cheap/# best ed pills non prescription

top 10 pharmacies in india online pharmacy india top 10 online pharmacy in india

canadian pharmacy online reviews: cross border pharmacy canada – canadian pharmacy meds review

http://canadianinternationalpharmacy.pro/# ordering drugs from canada

https://canadianinternationalpharmacy.pro/# canadian pharmacy no scripts

online shopping pharmacy india india pharmacy buy prescription drugs from india

http://edpill.cheap/# how to cure ed

best medication for ed otc ed pills cheapest ed pills online

my canadian pharmacy review: canadian drug – trusted canadian pharmacy

https://medicinefromindia.store/# indianpharmacy com

cheap ed drugs treatments for ed best ed pills

http://medicinefromindia.store/# Online medicine order

viagra without doctor prescription: cheap cialis – how to get prescription drugs without doctor

mexican drugstore online buying prescription drugs in mexico mexican mail order pharmacies

https://medicinefromindia.store/# top online pharmacy india

http://edpill.cheap/# best ed treatment

mexican pharmacy mexico drug stores pharmacies best online pharmacies in mexico

http://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# non prescription ed pills

prescription drugs generic cialis without a doctor prescription viagra without doctor prescription

http://canadianinternationalpharmacy.pro/# canadian online pharmacy

tadalafil without a doctor’s prescription generic cialis without a doctor prescription viagra without doctor prescription

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa medication from mexico pharmacy

http://medicinefromindia.store/# indian pharmacies safe

https://canadianinternationalpharmacy.pro/# canadian pharmacy sarasota

gnc ed pills best ed medications ed medications online

https://canadianinternationalpharmacy.pro/# canadapharmacyonline legit

prescription drugs cialis without a doctor prescription online prescription for ed meds

http://medicinefromindia.store/# best india pharmacy

http://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# best non prescription ed pills

best non prescription ed pills otc ed pills ed pills gnc

http://canadianinternationalpharmacy.pro/# canadian pharmacy online store

mexican drugstore online best online pharmacies in mexico п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# mexican rx online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexican mail order pharmacies

https://medicinefromindia.store/# online pharmacy india

https://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# prescription drugs

https://edpill.cheap/# otc ed pills

northern pharmacy canada legal to buy prescription drugs from canada www canadianonlinepharmacy

mexican pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican pharmacy medication from mexico pharmacy mexican drugstore online

mexico pharmacy buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs reputable mexican pharmacies online best online pharmacies in mexico

best online pharmacies in mexico buying prescription drugs in mexico online pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

medication from mexico pharmacy mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

best mexican online pharmacies mexican pharmaceuticals online mexican pharmaceuticals online

medicine in mexico pharmacies medicine in mexico pharmacies buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico pharmacy п»їbest mexican online pharmacies buying prescription drugs in mexico online

buying from online mexican pharmacy mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa buying prescription drugs in mexico

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexico pharmacies prescription drugs buying from online mexican pharmacy

medicine in mexico pharmacies best online pharmacies in mexico mexican drugstore online

mexican pharmacy best online pharmacies in mexico mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

reputable mexican pharmacies online mexican pharmacy mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

best online pharmacies in mexico best online pharmacies in mexico mexico pharmacy

mexican drugstore online best online pharmacies in mexico mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

medicine in mexico pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican mail order pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy best online pharmacies in mexico mexico drug stores pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies mexican drugstore online medication from mexico pharmacy

best online pharmacies in mexico mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexico drug stores pharmacies

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies п»їbest mexican online pharmacies medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican pharmaceuticals online mexican drugstore online purple pharmacy mexico price list

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexico drug stores pharmacies mexico pharmacy

mexican rx online best online pharmacies in mexico buying prescription drugs in mexico online

medication from mexico pharmacy mexico drug stores pharmacies medication from mexico pharmacy

medication from mexico pharmacy buying prescription drugs in mexico medicine in mexico pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies mexican drugstore online mexican mail order pharmacies

medication from mexico pharmacy best online pharmacies in mexico mexico drug stores pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online mexican pharmacy mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

buying prescription drugs in mexico online reputable mexican pharmacies online mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico drug stores pharmacies п»їbest mexican online pharmacies buying prescription drugs in mexico online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexico pharmacy best online pharmacies in mexico

medication from mexico pharmacy purple pharmacy mexico price list pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies best online pharmacies in mexico medicine in mexico pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican pharmacy reputable mexican pharmacies online mexican rx online

mexico drug stores pharmacies п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican pharmaceuticals online

purple pharmacy mexico price list п»їbest mexican online pharmacies buying from online mexican pharmacy

best mexican online pharmacies mexican drugstore online purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican mail order pharmacies п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexico pharmacy mexico drug stores pharmacies

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexico drug stores pharmacies medication from mexico pharmacy reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican pharmaceuticals online mexico pharmacy reputable mexican pharmacies online

buying prescription drugs in mexico buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa best online pharmacies in mexico mexico drug stores pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online mexican rx online best mexican online pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online mexican pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexico pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies reputable mexican pharmacies online mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican mail order pharmacies mexican drugstore online

buying prescription drugs in mexico online medication from mexico pharmacy buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican pharmacy mexican rx online best mexican online pharmacies

mexican pharmacy п»їbest mexican online pharmacies medication from mexico pharmacy

buying from online mexican pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy mexico pharmacy

mexican rx online reputable mexican pharmacies online pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

best online pharmacies in mexico purple pharmacy mexico price list medication from mexico pharmacy

reputable mexican pharmacies online mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs purple pharmacy mexico price list

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies medicine in mexico pharmacies reputable mexican pharmacies online

https://amoxil.cheap/# buy amoxicillin online with paypal

lisinopril online purchase lisinopril tabs 40mg zestril 10 mg price

prednisone 50 mg tablet canada: can you buy prednisone over the counter in canada – order prednisone online no prescription

https://amoxil.cheap/# amoxicillin over counter

https://buyprednisone.store/# buy prednisone tablets online

buy amoxicillin online mexico: order amoxicillin 500mg – amoxicillin 500mg capsules

amoxicillin tablet 500mg amoxicillin 500mg pill generic amoxil 500 mg

https://amoxil.cheap/# amoxicillin 750 mg price

stromectol price usa: ivermectin oral solution – ivermectin 50 mg

https://furosemide.guru/# furosemide 100 mg

cost of amoxicillin buy amoxicillin 250mg how much is amoxicillin prescription

furosemide 40mg: Buy Furosemide – furosemida 40 mg

http://amoxil.cheap/# amoxicillin 500mg buy online canada

lisinopril 20 mg tablet price lisinopril 12.5 mg tablets lisinopril drug

http://lisinopril.top/# lisinopril 100mcg

zestril online: prinivil 5 mg tablets – lisinopril 2.5 mg coupon

http://amoxil.cheap/# where can i buy amoxicillin online

how to buy amoxycillin: amoxicillin 500 mg – where to buy amoxicillin over the counter

lisinopril cheap brand lisinopril tablets lisinopril 10 mg

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin otc

amoxicillin for sale online: buy amoxicillin 500mg usa – amoxicillin 50 mg tablets

https://furosemide.guru/# furosemide 100mg

ivermectin cream 1 price of ivermectin liquid ivermectin 4

stromectol usa: ivermectin 50ml – ivermectin 4

http://lisinopril.top/# lisinopril 19 mg

http://buyprednisone.store/# can you buy prednisone in canada

lisinopril 40 mg daily: 3 lisinopril – prinivil online

prednisone 40mg prednisone 5 mg cheapest prednisone pills 10 mg

http://stromectol.fun/# cost of ivermectin

amoxicillin online pharmacy: amoxicillin 875 mg tablet – buy amoxicillin from canada

https://buyprednisone.store/# buy prednisone online uk

medication lisinopril 5 mg: lisinopril 20g – 1 lisinopril

lisinopril 60 mg tablet over the counter lisinopril lisinopril 20 mg best price

https://stromectol.fun/# buy liquid ivermectin

lisinopril cost uk: lisinopril 30 mg – order lisinopril online from canada

https://furosemide.guru/# lasix for sale

ivermectin 200mg cost of stromectol medication stromectol tablets

http://furosemide.guru/# lasix generic name

https://lisinopril.top/# medication lisinopril 10 mg

ivermectin price: stromectol tablets 3 mg – ivermectin 400 mg

furosemide Buy Lasix No Prescription buy furosemide online

https://furosemide.guru/# buy lasix online

https://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin lotion for lice

I just wanted to drop by and say how much I enjoy reading your blog. Asheville adores your work!

Your blog is a true masterpiece, crafted with care and passion. We’re proud supporters from Asheville!

prescription drug lisinopril cost of lisinopril 30 mg lisinopril 40 mg tablets

http://amoxil.cheap/# amoxicillin 500 capsule

Your posts always leave me feeling enlightened and inspired. Thank you for sharing your knowledge with us. Asheville sends its love!

Your blog is a sanctuary of wisdom and inspiration. We’re grateful readers from Asheville!

lisinopril uk: can i buy generic lisinopril online – order cheap lisinopril

https://furosemide.guru/# lasix online

Your posts always leave me feeling enlightened and inspired. Thank you for sharing your knowledge with us. Asheville sends its love!

I always look forward to your latest posts. They never fail to impress! Sending love from Asheville.

Your blog is a true reflection of your passion and expertise. Asheville is lucky to have you!

Your blog is a must-read for anyone seeking inspiration and knowledge. Asheville is lucky to have you!

lasix uses Buy Lasix No Prescription lasix 40mg

https://stromectol.fun/# buy ivermectin stromectol

Thank you for being a constant source of inspiration through your blog. Asheville is proud to support you!

Thank you for being a constant source of inspiration through your blog. Asheville is proud to support you!

Your blog is like a breath of fresh air. In Asheville, we’re big fans and can’t wait for more!

Thank you for enriching our lives with your wonderful blog. Asheville is blessed to have you!

Your blog is a sanctuary of wisdom and inspiration. We’re grateful readers from Asheville!

Thank you for being a constant source of inspiration through your blog. Asheville is proud to support you!

Your blog is like a ray of sunshine on a cloudy day – uplifting and inspiring. Sending love from Asheville!

Your blog is a sanctuary of wisdom and inspiration. We’re grateful readers from Asheville!

Your blog is a sanctuary of wisdom and inspiration. We’re grateful readers from Asheville!

Your blog is a testament to your dedication and expertise. We’re proud fans from Asheville!

Your blog is like a good friend – reliable, comforting, and always there when you need it. Sending love from Asheville!

Your writing is like a beacon of light in the darkness, guiding us towards knowledge and understanding. Asheville appreciates your blog!

Your writing is like a breath of fresh air, invigorating and rejuvenating. We’re proud followers from Asheville!

Your blog is a treasure chest of wisdom and insight. We’re grateful to be readers from Asheville!

Your writing has a way of touching hearts and minds. We’re proud supporters of your blog from Asheville!

Your blog is a true gift to the world. We’re big fans from Asheville!

Your blog is a treasure chest of wisdom and insight. We’re grateful to be readers from Asheville!

Thank you for sharing your expertise with the world through your blog. Asheville residents are grateful for your contributions.

lasix 100 mg tablet: Buy Lasix No Prescription – lasix for sale

https://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin generic cream

https://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin 4000

lisinopril 10mg prices compare lisinopril average cost prinivil 10 mg tablet

generic prednisone for sale: prednisone 2.5 mg price – 1 mg prednisone daily

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin buy

buy prednisone online canada: generic prednisone tablets – can i buy prednisone from canada without a script

http://furosemide.guru/# lasix furosemide

order lisinopril online lisinopril 10 mg brand name in india lisinopril generic over the counter

https://lisinopril.top/# lisinopril 40 mg for sale

stromectol cost: stromectol 3 mg – where to buy ivermectin

https://lisinopril.top/# lisinopril 10 mg canada cost

lasix 40 mg Buy Lasix lasix 100 mg

ivermectin brand: buy ivermectin stromectol – ivermectin 3mg price

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin 6

http://lisinopril.top/# lisinopril hct

lasix furosemide 40 mg: Buy Lasix – lasix pills

online shopping pharmacy india indian pharmacy paypal Online medicine order

https://indianph.xyz/# best online pharmacy india

top 10 online pharmacy in india

top online pharmacy india online shopping pharmacy india indian pharmacy

https://indianph.xyz/# top 10 online pharmacy in india

pharmacy website india

https://indianph.xyz/# Online medicine home delivery

world pharmacy india

https://indianph.com/# reputable indian online pharmacy

cheapest online pharmacy india

https://indianph.com/# buy prescription drugs from india

reputable indian pharmacies

https://indianph.com/# india online pharmacy

indian pharmacies safe

india pharmacy mail order mail order pharmacy india Online medicine home delivery

https://indianph.xyz/# buy prescription drugs from india

indian pharmacy paypal

https://indianph.com/# reputable indian pharmacies

best online pharmacy india

indianpharmacy com Online medicine order mail order pharmacy india

http://indianph.com/# top 10 pharmacies in india

indian pharmacy

tamoxifen cost: tamoxifen side effects forum – how does tamoxifen work

http://nolvadex.guru/# tamoxifen hip pain

buy doxycycline online doxycycline 100mg dogs doxycycline 150 mg

cipro pharmacy: buy cipro online canada – ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet price

https://cytotec24.com/# Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

https://cytotec24.com/# buy cytotec online fast delivery

buy cytotec pills online cheap: buy cytotec over the counter – buy cytotec over the counter

doxycycline order online doxycycline 500mg doxycycline 50mg

http://nolvadex.guru/# natural alternatives to tamoxifen

doxycycline mono: where to get doxycycline – buy generic doxycycline

http://diflucan.pro/# diflucan over the counter

diflucan mexico can you buy diflucan over the counter in australia buy diflucan online canada

http://cipro.guru/# cipro ciprofloxacin

order doxycycline online: doxycycline 50 mg – doxycycline 50 mg

http://cytotec24.shop/# buy cytotec online fast delivery

buy misoprostol over the counter: buy cytotec pills online cheap – buy cytotec pills online cheap

diflucan online pharmacy diflucan coupon canada where to buy diflucan 1

https://cytotec24.shop/# Cytotec 200mcg price

https://cipro.guru/# cipro 500mg best prices

diflucan 200 diflucan 100 mg tablet diflucan over the counter nz

http://cytotec24.com/# buy cytotec over the counter

http://doxycycline.auction/# order doxycycline

diflucan 200 mg tablet diflucan buy diflucan 150 mg cost

https://nolvadex.guru/# tamoxifen effectiveness

https://cytotec24.shop/# buy cytotec over the counter

how much is a diflucan pill diflucan online buy cost of diflucan prescription in mexico

https://diflucan.pro/# diflucan prescription australia

http://cipro.guru/# ciprofloxacin generic price

Angela Beyaz modeli: Angela Beyaz modeli – Angela White

http://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades filmleri

https://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox video

eva elfie filmleri: eva elfie – eva elfie filmleri

http://abelladanger.online/# abella danger izle

http://angelawhite.pro/# Angela Beyaz modeli

http://abelladanger.online/# abella danger video

eva elfie video: eva elfie – eva elfie video

https://abelladanger.online/# abella danger video

https://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox izle

lana rhoades video: lana rhoades modeli – lana rhoades izle

https://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie modeli

http://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie izle

http://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox video

lana rhoades filmleri: lana rhoades video – lana rhoades modeli

https://abelladanger.online/# abella danger izle

https://abelladanger.online/# abella danger izle

lana rhoades izle: lana rhoades – lana rhoades filmleri

http://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie izle

http://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox izle

Angela White filmleri: ?????? ???? – Angela White video

http://angelawhite.pro/# Angela Beyaz modeli

http://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie filmleri

eva elfie izle: eva elfie modeli – eva elfie izle

https://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White

http://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox izle

Angela White: Angela White izle – Angela White

https://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades izle

https://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhodes

https://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie filmleri

eva elfie video: eva elfie filmleri – eva elfie modeli

http://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie

http://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie filmleri

eva elfie modeli: eva elfie filmleri – eva elfie modeli

https://angelawhite.pro/# Angela Beyaz modeli

https://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox izle

http://abelladanger.online/# Abella Danger

?????? ????: ?????? ???? – Angela White filmleri

https://abelladanger.online/# abella danger izle

https://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie

eva elfie izle: eva elfie – eva elfie filmleri

https://abelladanger.online/# abella danger izle

http://miamalkova.life/# mia malkova latest

lana rhoades unleashed: lana rhoades full video – lana rhoades hot

http://sweetiefox.pro/# sweetie fox full

lana rhoades pics: lana rhoades boyfriend – lana rhoades hot

http://miamalkova.life/# mia malkova girl

https://evaelfie.site/# eva elfie videos

sweetie fox: sweetie fox video – sweetie fox cosplay

lana rhoades: lana rhoades hot – lana rhoades pics

https://lanarhoades.pro/# lana rhoades full video

lana rhoades unleashed: lana rhoades full video – lana rhoades hot

http://miamalkova.life/# mia malkova

sweetie fox: sweetie fox new – sweetie fox

https://evaelfie.site/# eva elfie photo

eva elfie full videos: eva elfie new video – eva elfie new video

mia malkova photos: mia malkova full video – mia malkova photos

http://miamalkova.life/# mia malkova hd

sweetie fox: fox sweetie – sweetie fox cosplay

http://sweetiefox.pro/# sweetie fox new

mia malkova girl: mia malkova latest – mia malkova latest

https://sweetiefox.pro/# sweetie fox

mia malkova hd: mia malkova latest – mia malkova hd

http://evaelfie.site/# eva elfie hd

lana rhoades pics: lana rhoades full video – lana rhoades videos

http://miamalkova.life/# mia malkova latest

mia malkova full video: mia malkova new video – mia malkova movie

http://evaelfie.site/# eva elfie full videos

https://aviatormocambique.site/# aviator

aviator mz: aviator – aviator moçambique

http://aviatormalawi.online/# aviator

pin-up: pin up cassino online – pin-up cassino

aviator bet: aviator moçambique – como jogar aviator em moçambique

https://aviatormocambique.site/# aviator mz

pin up aviator: pin up – aviator pin up casino

pin-up casino: cassino pin up – aviator pin up casino

http://aviatorghana.pro/# aviator login

aviator jogar: pin up aviator – aviator game

jogo de aposta: aviator jogo de aposta – melhor jogo de aposta para ganhar dinheiro

aviator online: aviator – aviator online

pin up aviator: aviator hilesi – aviator

aviator jogo de aposta: jogos que dão dinheiro – jogos que dão dinheiro

aviator jogar: estrela bet aviator – aviator game

aviator oyna: aviator oyna – aviator oyunu

melhor jogo de aposta: jogo de aposta online – depósito mínimo 1 real

zithromax z-pak price without insurance – https://azithromycin.pro/zithromax-suspension.html zithromax capsules australia

aviator betting game: aviator game online – aviator bet

como jogar aviator em moçambique: aviator online – aviator online

where can i buy zithromax in canada: zithromax generic name where can i get zithromax

pin-up: pin-up casino login – pin-up casino entrar

zithromax for sale 500 mg: does zithromax treat uti zithromax 250mg

india pharmacy: online pharmacy usa – indian pharmacy online indianpharm.store

mexican rx online: medication from mexico pharmacy – purple pharmacy mexico price list mexicanpharm.shop

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: order online from a Mexican pharmacy – mexican pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

http://canadianpharmlk.shop/# canadian pharmacy 365 canadianpharm.store

https://indianpharm24.com/# top online pharmacy india indianpharm.store

http://indianpharm24.shop/# indian pharmacies safe indianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm24.shop/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexicanpharm.shop

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican mail order pharmacies mexicanpharm.shop

https://indianpharm24.shop/# india pharmacy indianpharm.store

canadian pharmacy india: CIPA approved pharmacies – canadian pharmacy prices canadianpharm.store

https://indianpharm24.com/# india pharmacy indianpharm.store

https://canadianpharmlk.com/# reputable canadian online pharmacies canadianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm24.com/# mexican mail order pharmacies mexicanpharm.shop

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: Mexico pharmacy price list – mexican pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

http://mexicanpharm24.shop/# mexico pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

http://canadianpharmlk.com/# canadian drug pharmacy canadianpharm.store

http://canadianpharmlk.com/# online canadian pharmacy reviews canadianpharm.store

Online medicine order: online pharmacy in india – Online medicine home delivery indianpharm.store

https://indianpharm24.com/# world pharmacy india indianpharm.store

https://indianpharm24.com/# buy medicines online in india indianpharm.store

https://canadianpharmlk.shop/# canadian compounding pharmacy canadianpharm.store

Online medicine order: Pharmacies in India that ship to USA – indian pharmacy indianpharm.store

http://canadianpharmlk.shop/# legitimate canadian pharmacy online canadianpharm.store

can i buy generic clomid without prescription: where can i get generic clomid without prescription – buy clomid without prescription

prednisone pill prices: prednisone for gout – prednisone 5mg price

https://amoxilst.pro/# amoxicillin pills 500 mg

amoxicillin over the counter in canada: drinking on amoxicillin – generic amoxicillin cost

amoxicillin pills 500 mg: amoxil generic – buy amoxicillin 500mg canada

https://amoxilst.pro/# amoxicillin 500 capsule

prednisone 10mg tablet cost: what is the lowest dose of prednisone you can take – prednisone 60 mg price

amoxicillin online canada: cephalexin vs amoxicillin – amoxicillin no prescipion

http://prednisonest.pro/# prednisone 10 mg tablets

amoxicillin 500 mg where to buy: amoxicillin brand name – where to buy amoxicillin

order clomid without a prescription: clomid dosage for men – can i get cheap clomid no prescription

clomid sale: can i purchase generic clomid without rx – can i order generic clomid

http://clomidst.pro/# can i buy clomid without prescription

prednisone 10 mg: alcohol and prednisone – buy prednisone 10mg

prednisone 5 mg tablet price: prednisone 54899 – prednisone tablets india

http://amoxilst.pro/# over the counter amoxicillin

buy amoxicillin 500mg canada: what is amoxicillin used for – amoxicillin 500mg pill

pills no prescription: online medicine without prescription – best website to buy prescription drugs

https://pharmnoprescription.pro/# no prescription online pharmacies

edmeds: erection pills online – best ed meds online

canada pharmacy not requiring prescription: Best online pharmacy – canadian prescription pharmacy

https://pharmnoprescription.pro/# no prescription canadian pharmacy

ed pills: boner pills online – ed medications cost

pharmacy discount coupons: mexican pharmacy online – canada pharmacy coupon

http://pharmnoprescription.pro/# buy pain meds online without prescription

cheap ed pills online: online erectile dysfunction – where to buy ed pills

buying prescription medicine online: online pharmacy that does not require a prescription – legitimate online pharmacy no prescription

http://onlinepharmacy.cheap/# cheapest pharmacy to fill prescriptions with insurance

ed online prescription: online ed medicine – pills for erectile dysfunction online

pharmacy no prescription required: mexican online pharmacy – reputable online pharmacy no prescription

ed pills for sale: best ed medication online – how to get ed pills

https://onlinepharmacy.cheap/# online pharmacy no prescription needed

no prescription: canadian pharmacy prescription – buy prescription drugs on line

no prescription pharmacy paypal: Cheapest online pharmacy – rx pharmacy coupons

pharmacy no prescription: canada pharmacies online prescriptions – canadian pharmacy online no prescription needed

https://indianpharm.shop/# buy prescription drugs from india

Online medicine order: online pharmacy india – buy prescription drugs from india

http://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# buying online prescription drugs

mexican pharmacy: buying prescription drugs in mexico – purple pharmacy mexico price list

best online pharmacy india: buy medicines online in india – mail order pharmacy india

https://mexicanpharm.online/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

buy medications online without prescription: online pharmacy canada no prescription – canada mail order prescription

real canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy checker – canada drugs online

http://canadianpharm.guru/# canadianpharmacyworld com

canada pharmacy reviews: recommended canadian pharmacies – canadian pharmacy price checker

medications online without prescription: non prescription pharmacy – buying prescription drugs from canada online

https://indianpharm.shop/# Online medicine order

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

Online medicine order: india online pharmacy – india pharmacy mail order

best canadian pharmacy to order from: canada pharmacy – canada rx pharmacy world

http://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# best online pharmacy no prescription

cheap drugs no prescription: canadian prescription drugstore review – canadian pharmacy online no prescription needed

reputable indian online pharmacy: buy prescription drugs from india – indian pharmacy

http://indianpharm.shop/# buy prescription drugs from india

canadian drugs no prescription: buy medication online without prescription – canada pharmacies online prescriptions

canadian drug pharmacy: canadian pharmacy ltd – canadian pharmacy king reviews

canadian pharmacy india pharmacy – best online pharmacy

http://canadianpharm.guru/# onlinecanadianpharmacy

mexican drugstore online: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican pharmacy

best canadian online pharmacy: canadian online pharmacy reviews – my canadian pharmacy rx

northwest canadian pharmacy: buy drugs from canada – canadian pharmacy phone number

http://canadianpharm.guru/# onlinecanadianpharmacy

indian pharmacy paypal: mail order pharmacy india – buy medicines online in india

world pharmacy india: indian pharmacies safe – indian pharmacy

https://indianpharm.shop/# reputable indian pharmacies

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican rx online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

canadianpharmacymeds: canadian mail order pharmacy – canadian pharmacy online store

canadian rx prescription drugstore: canada mail order prescriptions – online no prescription pharmacy

http://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# buy prescription drugs without a prescription

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexico drug stores pharmacies – purple pharmacy mexico price list

indian pharmacies safe: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – Online medicine home delivery

https://canadianpharm.guru/# canadian pharmacy india

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – buying from online mexican pharmacy

77 canadian pharmacy: best canadian pharmacy – maple leaf pharmacy in canada

https://mexicanpharm.online/# mexico pharmacy

mail order pharmacy india: india pharmacy – reputable indian pharmacies

safe reliable canadian pharmacy: canadian world pharmacy – canada ed drugs

mexican mail order pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

https://mexicanpharm.online/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

no prescription canadian pharmacy: no prescription canadian pharmacy – order prescription drugs online without doctor

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: buying from online mexican pharmacy – purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://mexicanpharm.online/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

vipps canadian pharmacy: canada pharmacy world – best canadian online pharmacy reviews

https://sweetbonanza.bid/# sweet bonanza nasil oynanir

aviator oyunu 50 tl: aviator oyna slot – aviator oyna

https://sweetbonanza.bid/# sweet bonanza bahis

http://gatesofolympus.auction/# pragmatic play gates of olympus

aviator pin up: pin up casino – pin up casino indir

http://sweetbonanza.bid/# sweet bonanza slot

pin up casino giris: aviator pin up – pin-up bonanza

https://aviatoroyna.bid/# aviator oyunu

http://slotsiteleri.guru/# slot siteleri güvenilir

en guvenilir slot siteleri: guvenilir slot siteleri 2024 – casino slot siteleri

pin up indir: pin up 7/24 giris – pin-up casino giris

https://pinupgiris.fun/# pin up casino güncel giris

aviator oyna 20 tl: aviator ucak oyunu – aviator mostbet

http://aviatoroyna.bid/# aviator hilesi ücretsiz

http://aviatoroyna.bid/# aviator casino oyunu

gates of olympus taktik: gates of olympus demo free spin – gates of olympus s?rlar?

http://aviatoroyna.bid/# aviator bahis

http://sweetbonanza.bid/# sweet bonanza kazanma saatleri

gates of olympus demo free spin: gates of olympus s?rlar? – gates of olympus demo turkce oyna

https://gatesofolympus.auction/# gates of olympus nasil para kazanilir

aviator hile: aviator oyna – aviator oyunu 20 tl

https://gatesofolympus.auction/# gates of olympus 1000 demo

slot siteleri bonus veren: en yeni slot siteleri – yasal slot siteleri

http://aviatoroyna.bid/# aviator uçak oyunu

best online pharmacy india indian pharmacy delivery pharmacy website india

best india pharmacy indian pharmacy delivery india pharmacy

mexican drugstore online: Mexican Pharmacy Online – mexican pharmaceuticals online

canadian pharmacy no scripts Certified Canadian Pharmacy best canadian pharmacy

indian pharmacy paypal: indian pharmacies safe – cheapest online pharmacy india

canada pharmacy online: Large Selection of Medications – 77 canadian pharmacy

mexican mail order pharmacies: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico drug stores pharmacies Online Pharmacies in Mexico mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

canadian drug prices: canadian pharmacy online store – canada drugs online review

best online pharmacy india: Healthcare and medicines from India – Online medicine home delivery

trustworthy canadian pharmacy pills now even cheaper onlinecanadianpharmacy

online pharmacy india: indian pharmacy delivery – top 10 online pharmacy in india

indian pharmacy online: indian pharmacy – legitimate online pharmacies india

pharmacy website india Generic Medicine India to USA top 10 online pharmacy in india

mexico drug stores pharmacies: Online Pharmacies in Mexico – buying from online mexican pharmacy

cheapest online pharmacy india: indian pharmacy delivery – world pharmacy india

mexican pharmacy Mexican Pharmacy Online mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

buying from online mexican pharmacy mexico drug stores pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexican pharmacy – mexican rx online

top 10 online pharmacy in india indian pharmacy best online pharmacy india

canadian pharmacies compare: Large Selection of Medications – legitimate canadian pharmacy online

canadian neighbor pharmacy: Certified Canadian Pharmacy – canadian online drugs

where to get zithromax zithromax without prescription zithromax coupon

http://prednisoneall.shop/# prednisone uk price

prednisone 250 mg buy prednisone online without a prescription can i buy prednisone online without prescription

http://prednisoneall.com/# where to buy prednisone uk

https://zithromaxall.com/# zithromax tablets

zithromax for sale online can you buy zithromax over the counter in australia zithromax pill

https://clomidall.com/# generic clomid no prescription

https://prednisoneall.shop/# prednisone tablets

amoxicillin 500mg capsules amoxicillin capsules 250mg where to buy amoxicillin 500mg without prescription

http://clomidall.shop/# can i buy cheap clomid tablets

how to buy clomid without prescription where can i get clomid without prescription order cheap clomid without dr prescription

http://amoxilall.com/# can i buy amoxicillin over the counter

amoxicillin without prescription amoxicillin 500mg buy online canada where can you buy amoxicillin over the counter

http://prednisoneall.shop/# prednisone 5mg price

can you buy generic clomid for sale where to buy generic clomid online cost generic clomid without insurance

http://zithromaxall.com/# zithromax capsules price

http://zithromaxall.shop/# zithromax prescription

how to buy cheap clomid prices clomid sale how to get generic clomid pill

http://zithromaxall.com/# purchase zithromax z-pak

buy amoxicillin without prescription generic amoxicillin amoxicillin over counter

http://prednisoneall.shop/# buy prednisone online usa

http://zithromaxall.com/# how to get zithromax

zithromax capsules australia where to get zithromax over the counter generic zithromax online paypal

buy kamagra online usa: Kamagra Oral Jelly Price – kamagra

cheap viagra Cheap Viagra 100mg Cheap Viagra 100mg

buy cialis pill: cheapest cialis – cialis generic

Order Viagra 50 mg online sildenafil iq buy Viagra over the counter

cheapest viagra: cheapest viagra – Cheapest Sildenafil online

Kamagra 100mg price: Kamagra gel – Kamagra Oral Jelly

Kamagra 100mg price Kamagra gel cheap kamagra

cheapest viagra: cheapest viagra – sildenafil online

Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription cheapest cialis Buy Cialis online

Buy Tadalafil 5mg: cialis without a doctor prescription – Buy Tadalafil 10mg

Cialis 20mg price: Tadalafil Tablet – Cialis without a doctor prescription

https://tadalafiliq.com/# Cialis without a doctor prescription

Tadalafil Tablet: cheapest cialis – Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription

https://sildenafiliq.xyz/# Sildenafil Citrate Tablets 100mg

buy Viagra over the counter: generic ed pills – buy Viagra over the counter

sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra Kamagra gel super kamagra

cheap kamagra: Kamagra gel – Kamagra 100mg

https://sildenafiliq.com/# buy Viagra over the counter

Kamagra 100mg price: Sildenafil Oral Jelly – buy Kamagra

Generic Cialis price tadalafil iq cialis for sale

https://tadalafiliq.shop/# Buy Tadalafil 20mg

buy kamagra online usa: Sildenafil Oral Jelly – sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra

over the counter sildenafil Viagra online price Order Viagra 50 mg online

Generic Tadalafil 20mg price: cheapest cialis – Buy Tadalafil 20mg

https://kamagraiq.shop/# Kamagra 100mg

sildenafil over the counter: cheapest viagra – Cheapest Sildenafil online

Cialis over the counter cheapest cialis Cialis over the counter

http://sildenafiliq.com/# buy Viagra online

generic sildenafil: best price on viagra – Order Viagra 50 mg online

cheap viagra: sildenafil iq – Viagra online price

http://canadianpharmgrx.com/# safe online pharmacies in canada

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs online pharmacy in Mexico mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

http://mexicanpharmgrx.com/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://mexicanpharmgrx.com/# mexican drugstore online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexican pharmacy mexican rx online

https://canadianpharmgrx.com/# canadian pharmacy 365

https://canadianpharmgrx.xyz/# onlinecanadianpharmacy

canada rx pharmacy world Pharmacies in Canada that ship to the US canadian pharmacy india

http://canadianpharmgrx.xyz/# pharmacy canadian

best canadian online pharmacy My Canadian pharmacy best rated canadian pharmacy

https://indianpharmgrx.com/# legitimate online pharmacies india

world pharmacy india indian pharmacy cheapest online pharmacy india

https://mexicanpharmgrx.shop/# best mexican online pharmacies

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs Pills from Mexican Pharmacy mexico pharmacy

http://indianpharmgrx.com/# world pharmacy india

http://canadianpharmgrx.xyz/# reliable canadian pharmacy

top 10 online pharmacy in india indian pharmacy top online pharmacy india

https://canadianpharmgrx.xyz/# canadian pharmacy meds

https://indianpharmgrx.shop/# online pharmacy india

pet meds without vet prescription canada International Pharmacy delivery canadian pharmacy oxycodone

https://mexicanpharmgrx.shop/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://canadianpharmgrx.xyz/# prescription drugs canada buy online

online shopping pharmacy india Healthcare and medicines from India Online medicine home delivery

tamoxifen chemo: tamoxifen for gynecomastia reviews – tamoxifen postmenopausal

nolvadex price tamoxifen 20 mg tablet tamoxifen men

tamoxifen alternatives premenopausal: tamoxifen rash pictures – nolvadex 10mg

buy ciprofloxacin over the counter ciprofloxacin order online ciprofloxacin over the counter

cytotec buy online usa: buy cytotec in usa – buy cytotec over the counter

cipro ciprofloxacin ciprofloxacin generic cipro ciprofloxacin

Misoprostol 200 mg buy online: purchase cytotec – buy misoprostol over the counter

medicine diflucan price: diflucan pill otc – can you buy diflucan over the counter

diflucan 200mg tab ordering diflucan generic diflucan online cheap

price of diflucan in south africa: diflucan oral – can you buy diflucan over the counter in australia

diflucan 300 mg diflucan coupon canada diflucan pill otc

diflucan gel: diflucan 15 mg – diflucan 150 mg tablet price in india

buy doxycycline online how to buy doxycycline online doxycycline 500mg

tamoxifen cancer: effexor and tamoxifen – how to get nolvadex

diflucan tablets price: diflucan where to buy uk – diflucan 150 mg prescription

cipro antibiotics cipro ciprofloxacin generic

buy cytotec: cytotec abortion pill – buy cytotec in usa

cytotec pills buy online: buy cytotec pills – Cytotec 200mcg price

buy doxycycline online without prescription: doxycycline 100mg – buy doxycycline without prescription

buy cipro online without prescription buy generic ciprofloxacin cipro online no prescription in the usa

buy diflucan otc: buy cheap diflucan online – where to get diflucan otc

buy doxycycline for dogs: buy doxycycline – how to buy doxycycline online

diflucan 150 mg fluconazole diflucan cost in india diflucan 150mg

order cytotec online: buy cytotec – buy cytotec pills online cheap

tamoxifen adverse effects: tamoxifen therapy – nolvadex 10mg

zithromax without prescription: how to get zithromax – buy zithromax online fast shipping

prednisone online pharmacy online order prednisone 10mg purchase prednisone canada

cost of amoxicillin 875 mg: buy amoxicillin 250mg – buy amoxicillin 250mg

can i buy amoxicillin over the counter amoxicillin 500 mg for sale amoxicillin pharmacy price

can you buy amoxicillin uk: buying amoxicillin in mexico – amoxicillin 500 mg tablet price

http://stromectola.top/# cost of stromectol

buy cheap clomid no prescription cheap clomid pill where to buy generic clomid now

where buy cheap clomid now: where to buy cheap clomid without prescription – can i get generic clomid without a prescription

ivermectin buy uk: ivermectin lotion price – buy ivermectin uk

http://prednisonea.store/# prednisone online australia

stromectol tablet 3 mg where to buy ivermectin cream ivermectin 3mg for lice

amoxicillin for sale: how to buy amoxycillin – amoxicillin price canada

http://amoxicillina.top/# amoxicillin 500 mg without prescription

50 mg prednisone from canada: prednisone 10 mg tablet cost – online prednisone

ivermectin 50 ivermectin brand stromectol 3 mg tablets price

http://prednisonea.store/# where can i get prednisone over the counter

http://medicationnoprescription.pro/# prescription drugs canada

cheapest online ed treatment order ed pills online ed pills for sale

http://medicationnoprescription.pro/# how to get prescription drugs from canada

buying prescription medicine online: pills no prescription – buy prescription online

https://medicationnoprescription.pro/# buying prescription drugs in india

cheapest pharmacy for prescriptions cheapest pharmacy to fill prescriptions without insurance canadian online pharmacy no prescription

buy ed pills online: buy ed medication – ed pills for sale

http://onlinepharmacyworld.shop/# cheapest pharmacy to fill prescriptions without insurance

online medication without prescription buy prescription drugs online without doctor non prescription online pharmacy india

https://medicationnoprescription.pro/# canada drugs no prescription

erectile dysfunction online prescription: online erectile dysfunction – where to buy erectile dysfunction pills

best no prescription online pharmacy: canada prescription online – online medicine without prescription

non prescription medicine pharmacy canadian prescription pharmacy cheapest pharmacy prescription drugs

http://medicationnoprescription.pro/# pills no prescription

best online ed medication: ed online prescription – best ed medication online

http://onlinepharmacyworld.shop/# canadian pharmacy world coupon code

ed online pharmacy online ed treatments ed treatment online

http://casinvietnam.com/# casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam: choi casino tr?c tuy?n trên di?n tho?i – casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam

game c? b?c online uy tín: dánh bài tr?c tuy?n – casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam

http://casinvietnam.com/# casino tr?c tuy?n

web c? b?c online uy tín: casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam – casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam

http://casinvietnam.com/# web c? b?c online uy tin

dánh bài tr?c tuy?n: dánh bài tr?c tuy?n – casino tr?c tuy?n

http://casinvietnam.com/# casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam

choi casino tr?c tuy?n trên di?n tho?i: casino tr?c tuy?n – casino tr?c tuy?n uy tín

http://casinvietnam.shop/# game c? b?c online uy tin

choi casino tr?c tuy?n trên di?n tho?i: choi casino tr?c tuy?n trên di?n tho?i – web c? b?c online uy tín

choi casino tr?c tuy?n trên di?n tho?i: casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam – web c? b?c online uy tín

https://casinvietnam.shop/# game c? b?c online uy tin

game c? b?c online uy tín: game c? b?c online uy tín – game c? b?c online uy tín

casino tr?c tuy?n uy tin casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam game c? b?c online uy tin

casino tr?c tuy?n web c? b?c online uy tin choi casino tr?c tuy?n tren di?n tho?i

http://casinvietnam.com/# casino tr?c tuy?n

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam: casino tr?c tuy?n – casino tr?c tuy?n uy tín

dánh bài tr?c tuy?n: casino tr?c tuy?n – web c? b?c online uy tín

https://casinvietnam.shop/# choi casino tr?c tuy?n tren di?n tho?i

choi casino tr?c tuy?n tren di?n tho?i casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam casino tr?c tuy?n

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam: casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam – casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam

http://casinvietnam.com/# casino tr?c tuy?n uy tin

choi casino tr?c tuy?n tren di?n tho?i game c? b?c online uy tin casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam

game c? b?c online uy tín: web c? b?c online uy tín – dánh bài tr?c tuy?n

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam

http://casinvietnam.com/# casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam: casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam – casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam

game c? b?c online uy tin danh bai tr?c tuy?n danh bai tr?c tuy?n

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam: casino online uy tín – casino tr?c tuy?n uy tín

http://mexicoph24.life/# mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

online shopping pharmacy india Cheapest online pharmacy best india pharmacy

https://mexicoph24.life/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

top 10 online pharmacy in india buy medicines from India top 10 online pharmacy in india

https://indiaph24.store/# online pharmacy india

mexico drug stores pharmacies: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – mexican mail order pharmacies

online pharmacy india buy medicines from India online shopping pharmacy india

https://mexicoph24.life/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexico drug stores pharmacies Mexican Pharmacy Online purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://mexicoph24.life/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

canadian pharmacy near me Certified Canadian Pharmacies canadianpharmacy com

https://indiaph24.store/# top 10 pharmacies in india

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa medicine in mexico pharmacies mexican pharmacy

https://mexicoph24.life/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

best rated canadian pharmacy Certified Canadian Pharmacies legit canadian pharmacy

https://canadaph24.pro/# canadian discount pharmacy

canadian valley pharmacy Licensed Canadian Pharmacy canadian pharmacy victoza

https://indiaph24.store/# india pharmacy mail order

reputable indian online pharmacy indian pharmacy online shopping pharmacy india

https://canadaph24.pro/# canadian valley pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexican pharmacy best online pharmacies in mexico

http://canadaph24.pro/# rate canadian pharmacies

http://mexicoph24.life/# mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

canadian valley pharmacy Prescription Drugs from Canada canadian pharmacy 24 com

https://canadaph24.pro/# canada pharmacy online legit

canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacies canadian world pharmacy

https://canadaph24.pro/# canadian pharmacy meds

top 10 pharmacies in india indian pharmacy online pharmacy india

https://mexicoph24.life/# best online pharmacies in mexico

my canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacies canadian 24 hour pharmacy

http://canadaph24.pro/# online pharmacy canada

canadian pharmacy victoza Large Selection of Medications from Canada ed meds online canada

https://mexicoph24.life/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

best india pharmacy Cheapest online pharmacy cheapest online pharmacy india

http://mexicoph24.life/# mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican drugstore online mexican pharmacy mexican pharmaceuticals online

http://canadaph24.pro/# canadian pharmacies online

buying from online mexican pharmacy Online Pharmacies in Mexico mexican pharmaceuticals online

http://canadaph24.pro/# canadian discount pharmacy

mexican mail order pharmacies mexico pharmacy buying prescription drugs in mexico

http://mexicoph24.life/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

safe reliable canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacies prescription drugs canada buy online

https://canadaph24.pro/# canada drugs online reviews

canadian pharmacy 24h com safe Prescription Drugs from Canada canadian pharmacy checker

http://indiaph24.store/# Online medicine order

ed drugs online from canada Licensed Canadian Pharmacy reliable canadian online pharmacy

http://mexicoph24.life/# medication from mexico pharmacy

pharmacy website india top online pharmacy india online shopping pharmacy india

https://canadaph24.pro/# canadian pharmacy

https://mexicoph24.life/# mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican pharmaceuticals online Online Pharmacies in Mexico best online pharmacies in mexico

http://canadaph24.pro/# best canadian pharmacy online

canadian compounding pharmacy canadian pharmacies canadian drug pharmacy

http://canadaph24.pro/# canadian online drugs

canadian pharmacy world canadian pharmacies certified canadian international pharmacy

http://mexicoph24.life/# medication from mexico pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies Online Pharmacies in Mexico mexican mail order pharmacies

https://canadaph24.pro/# certified canadian international pharmacy

canadapharmacyonline canadian pharmacy online ship to usa best canadian online pharmacy

http://mexicoph24.life/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

http://mexicoph24.life/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexican mail order pharmacies Mexican Pharmacy Online mexican drugstore online

http://mexicoph24.life/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

canadianpharmacy com Licensed Canadian Pharmacy drugs from canada

https://indiaph24.store/# indian pharmacy online

indian pharmacy online indian pharmacy fast delivery online pharmacy india

https://mexicoph24.life/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

http://indiaph24.store/# top 10 pharmacies in india

https://canadaph24.pro/# canadian world pharmacy

ed meds online canada canada drugstore pharmacy rx legitimate canadian pharmacies

http://indiaph24.store/# world pharmacy india

india online pharmacy buy medicines online in india top 10 online pharmacy in india

http://canadaph24.pro/# trusted canadian pharmacy

https://mexicoph24.life/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

purple pharmacy mexico price list medicine in mexico pharmacies reputable mexican pharmacies online

https://indiaph24.store/# india pharmacy mail order

canadian pharmacy store canadian pharmacy meds certified canadian pharmacy

http://mexicoph24.life/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

top online pharmacy india buy medicines from India mail order pharmacy india

https://indiaph24.store/# india online pharmacy

reputable indian online pharmacy reputable indian online pharmacy buy medicines online in india

http://canadaph24.pro/# canadian pharmacy india

mexican drugstore online: cheapest mexico drugs – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

http://ciprofloxacin.tech/# buy cipro online canada

tamoxifen citrate pct: tamoxifenworld – dcis tamoxifen

tamoxifen blood clots tamoxifen citrate pct tamoxifen generic

https://nolvadex.life/# liquid tamoxifen

cytotec pills buy online: Abortion pills online – cytotec abortion pill