Author: Julián Monge Nájera, Ecologist and Photographer

Hidden on top of a hill in Syria, tiny beings have lived for a thousand years, endowed -like the Christian knights who in July 1188 confronted there the troops of Sultan Saladin- with armor, digestive systems, muscles and brains. And their fight against a huge and merciless enemy lasts to this day.

This is how the ruins of the Castle or Fortress of Saladin in Syria now look. But in the 12th century, the fortress looked very different, because there a bloody fight took place between the Christian knights who occupied it, and the troops of Saladin, sultan of Egypt and Syria. After three days of siege, the Christians were defeated on July 30, 1188.

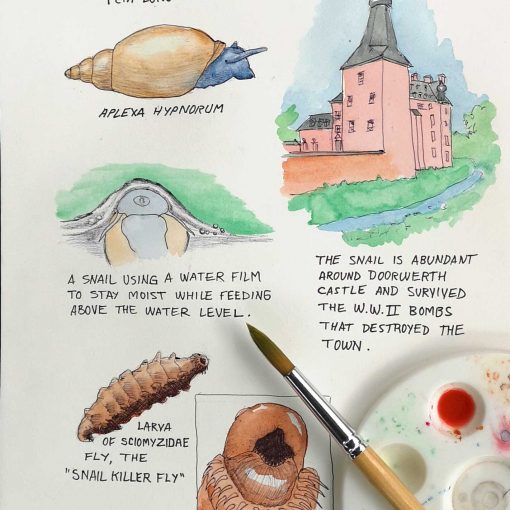

But long before this fight, tiny beings already lived in this impressive fortress, endowed -like the soldiers- with armor, digestive systems, muscles and brains: they were the Buliminus labrosus snails, which would be described by science thanks to specimens collected in the fortress in the 18th century¹.

Little is known about these snails, possibly due to the difficulty of studying a place devastated by war for at least 1000 years, and that today, when I write this (2020), suffers one of the great humanitarian tragedies of the early 21st century. But something is known, thanks to the fact that the snails also occur in Israel, where there is a strong scientific apparatus that has studied them, especially under the direction of the malacologist Joseph Alexander Heller².

How did the snails get in the fortress?

These snails live where the rock is rich in calcium carbonate, the same material found in chalk and our bones. They probably came inside crevices in the rocks used to build the fort; and maybe they also arrived by themselves from fields around the complex.

In the hills, these snails are more numerous on the sunnier southern side, but living there comes at a cost: they must be smaller to cope with desiccation and lack of food characteristic of the south side³.

No one knows if the same thing happens in the fortress’s south walls, but it would not be strange, because these snails are easily isolated and genetically differentiated⁴.

When the October rains arrive, they emerge from their estivation and mate. They deposit eggs in stone crevices, and babies are born in a couple of weeks. hiding during the day and going out at night to look for decomposing vegetation, their main food, which is not scarce in the fortress.

After two years of development, these snails reach maturity and produce the next generation.

During the drier periods, they live in groups of up to 150 animals under rocks and in crevices. But this population of sleepers hides two sad secrets. On the one hand, there is a mouse, of the genus Acomys, that eats them to obtain water and nutrients.

And on the other hand, like so many crusader knights who fell during the taking of the fortress, half of the sleeping snails will never wake up from their summer sleep, victims of heat, hunger and who knows how many invisible enemies that kill them inside their shells.

Originally published in Blog Biología Tropical: 14 july 2020

REFERENCES

¹ Olivier, G.A. (1804). Voyage dans l’Empire Othoman, l’Égypte et la Perse, fait par ordre du gouvernement, pendant les six premières années de la République. Paris, Francia: Agasse.

² Heller, J. (1975). The taxonomy, distribution and faunal succession of Buliminus (Pulmonata: Enidae) in Israel. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 57(1), 1-57.

³ Broza, M., & Nevo, E. (1996). Differentiation of the snail community on the North- and South-facing slopes of lower Nahal Oren (Mount Carmel, Israel). Israel Journal of Ecology and Evolution, 42(4) 411-424

⁴ Nevo, E, et al. (1982). Adaptive microgeographic differentiation of allozyme polymorphism in landsnails. Genetica, 59, 61–67.