Author: Julián Monge Nájera, Ecologist and Photographer

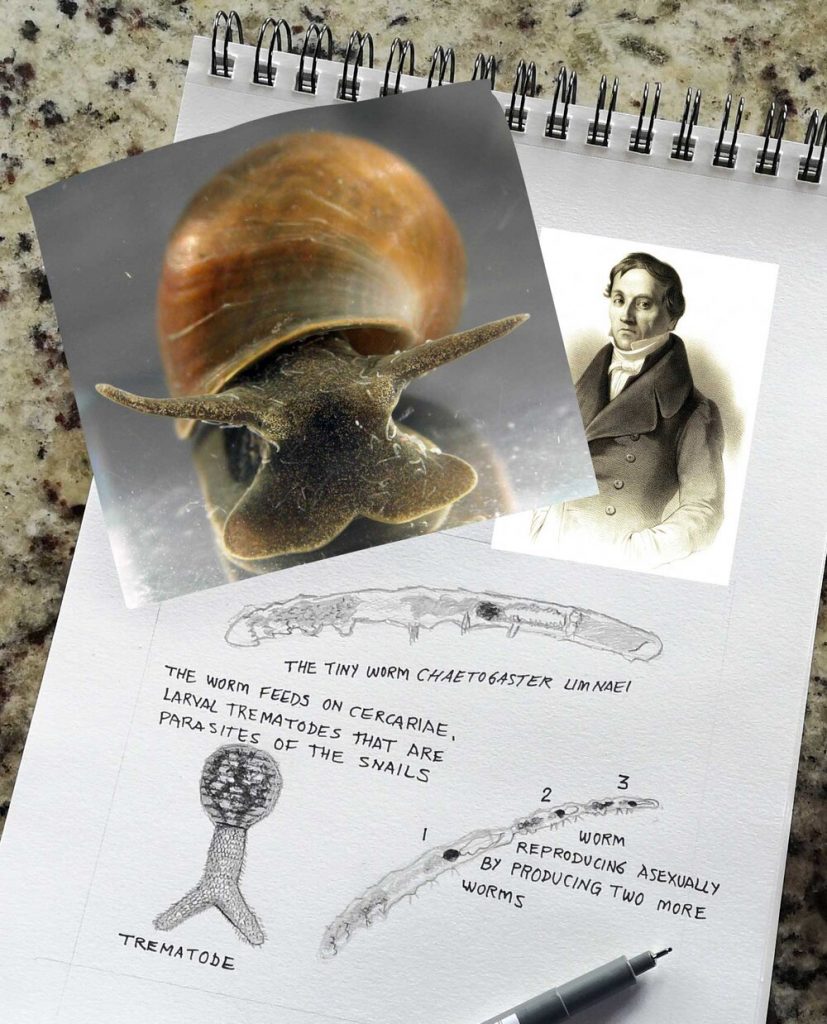

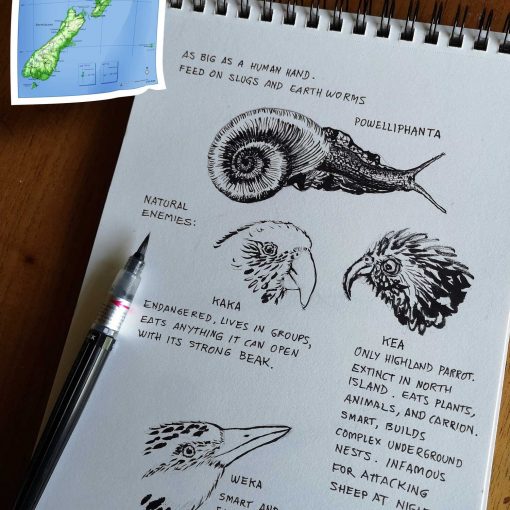

200 years ago, an Estonian zoologist described a strange worm that lived on the skin of freshwater snails. No one knew what it was doing there, and after 200 years, the answer is that it may be a protector of the snail, that it may be a parasite, or maybe both. It is important to me because I got to know these worms in person when I did my first scientific study almost four decades ago. They looked like dozens of liquid crystal tentacles protruding from the snail.

When Estonian zoologist Karl von Baer, founder of embryology, dedicated the species to Linnaeus in 1827, he knew that Chaetogaster limnaei worms always were associated with freshwater mollusks, whether they were small clams or snails of very different species. But what the worms were doing there was a mystery for decades, and even today, we still don’t know for sure if there is a single species of worm with two personalities or several species at the moment indistinguishable except for their behavior.

I met these tiny worms in the early 1980s, when, as a biology student at the University of Costa Rica, I saw what looked like crystalline tentacles in the pond snails that I had on my desk and that I had collected in a pond in San Pedro de Pavas (Costa Rica). They fascinated me, but I didn’t know what they were, and Dr. Pedro Morera helped me prepare some and send them to Brazil, to be identified by an expert whose name I no longer remember.

As far as I know, the first to write that there was something strange about these worms was E. Michelson, who in 1964 noticed that, in addition to protecting the snails from the parasite Schistosoma mansoni, some of these worms appeared inside the snail’s kidney, where they would hardly be doing something good; but he did not know what the worms were doing there¹.

The following year, Welsh zoologist L. Gruffydd solved the first part of the problem: the worm appeared to have two subspecies, one, Chaetogaster limnaei limnaei, lived on the skin of the snail and ate parasitic trematodes that approached the snail, thus protecting the snail. The other, Chaetogaster limnaei vaghini, penetrated the snails’s kidney and parasitized it. He added that when the snail died, the worms looked for new homes and took advantage of these difficult times to mate. However, without the shelter of the snail, many died².

A quarter-century later, a team of investigators realized that the relationship was more complex. Yes, the worms that stay on the skin eat everything that comes near and fits in their mouth, protecting the snail from parasitic flukes, but if too many worms occupy a snail, they become a burden, and the result is that overloaded snails lay fewer eggs³.

That same year, studying Chaetogaster on the snail Helisoma anceps, it was discovered that there are few worms in snails when the weather is very cold and that the worms prefer snails infected by the trematode Halipegus occidualis, whose slow larvae are easy to capture and eat⁴.

But the most interesting thing is that nothing can be generalized about these worms: the conclusions are contradictory from one study to another. They protect the snail Biomphalaria glabrata from the dreaded parasite Schistosoma mansoni, but ironically, snails with the parasite grow better and lay more eggs! In that case, the concept of the trematode as a parasite is questionable because, by definition, a parasite must do net damage to its host⁵.

Earthworms prefer snails of certain species; within a species the larger and more spacious individuals; and even if they are large, they avoid them if they lack parasites because only parasitized snails release the larvae that serve as food for the worm⁶.

For years I have wondered if these two «subspecies» are really two totally different species: vaghini, internal and clearly parasitic; and limnaei, which live outside and offer various degrees of benefit to the snail (depending on the environment and the species of snail). A 2015 study says no, the authors report that these worms are a rare case of “intraspecific plasticity” in which the same species can act as a parasite or as a protector and that it comes from an ancient worm that was an external parasite of mollusks⁷.

These researchers may be right, but I will continue to doubt until there is better evidence on the extremely complex relationship between these worms and their snails, which reminds us that, in nature, the answer is rarely as simple as it seems.

Originally published in Blog Biología Tropical: 12 august 2020

*Edited by Zaidett Barrientos, Katherine Bonilla and Carolina Seas

REFERENCES

¹ Michelson, E. H. (1964). The protective action of Chaetogaster limnaei on snails exposed to Schistosoma mansoni. The Journal of Parasitology, 50(3),441-444.

² Gruffydd, Ll. D. (1965). The Population Biology of Chaetogaster limnaei limnaei and Chaetogaster limnaei vaghini (Oligochaeta). Journal of Animal Ecology, 34(3), 667-690

³ Stoll, S., et al. (1991). Density-dependent relationship between Chaetogaster limnaei limnaei(Oligochaeta) and the freshwater snail Physa acuta (Pulmonata). The American Midland Naturalist, 125(2), 192-205.

⁴ Fernandez, J., et al. (1991). Population dynamics of Chaetogaster limnaei limnaei (Oligochaeta) as affected by a trematode parasite in Helisoma anceps (Gastropoda). The American Midland Naturalist, 125(2), 195-205.

⁵ Rodgers, J. K., et al. (2005). Multi-species interactions among a commensal (Chaetogaster limnaei limnaei), a parasite (Schistosoma mansoni), and an aquatic snail host (Biomphalaria glabrata). Journal of Parasitology, 91(3), 709-712.

⁶ McCaffrey, K. (2014). Patterns of multi-symbiont community interactions in California freshwater snails(Ph. D. Thesis). University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA.

⁷ Smythe, A. B., et al. (2015). Untangling the ecology, taxonomy, and evolution of Chaetogaster limnaei(Oligochaeta: Naididae) species complex. Journal of Parasitology, 101(3), 320-326.

3.989 ideas sobre “The mysterious crystalline tentacles of snails”

I love it when people get together and share thoughts. Great blog, stick with it!

https://amoxil.icu/# amoxicillin order online no prescription

where buy generic clomid generic clomid without dr prescription – cost of clomid pill

buy cytotec over the counter: cytotec buy online usa – buy cytotec over the counter

http://cytotec.icu/# buy cytotec

recommended canadian pharmacies: Pharmacies in Canada that ship to the US – canadian pharmacies compare canadianpharm.store

http://indianpharm.store/# indian pharmacy paypal indianpharm.store

canadian pharmacy online canadian pharmacy 24h com safe canadian valley pharmacy canadianpharm.store

best online canadian pharmacy: Pharmacies in Canada that ship to the US – canadian world pharmacy canadianpharm.store

http://canadianpharm.store/# best canadian pharmacy to buy from canadianpharm.store

buying prescription drugs in mexico: Online Mexican pharmacy – buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexicanpharm.shop

mail order pharmacy india top 10 pharmacies in india indian pharmacy online indianpharm.store

http://mexicanpharm.shop/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexicanpharm.shop

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexico drug stores pharmacies – best online pharmacies in mexico mexicanpharm.shop

mail order pharmacy india Indian pharmacy to USA online shopping pharmacy india indianpharm.store

indian pharmacy: order medicine from india to usa – pharmacy website india indianpharm.store

http://mexicanpharm.shop/# mexican pharmaceuticals online mexicanpharm.shop

canadian pharmacy store: Canadian Pharmacy – medication canadian pharmacy canadianpharm.store

https://indianpharm.store/# top 10 pharmacies in india indianpharm.store

mexican rx online Online Mexican pharmacy medication from mexico pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

medicine in mexico pharmacies: purple pharmacy mexico price list – mexican drugstore online mexicanpharm.shop

https://canadianpharm.store/# canadian pharmacy online canadianpharm.store

world pharmacy india international medicine delivery from india best online pharmacy india indianpharm.store

best canadian pharmacy online: Canadian International Pharmacy – canadian pharmacy no rx needed canadianpharm.store

http://indianpharm.store/# buy medicines online in india indianpharm.store

pharmacy website india Online medicine home delivery top online pharmacy india indianpharm.store

canadian pharmacy near me: Canadian International Pharmacy – online canadian drugstore canadianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm.shop/# mexican drugstore online mexicanpharm.shop

http://canadadrugs.pro/# fda approved canadian pharmacies

northwest canadian pharmacy canadian online pharmacies legitimate canadian drugstore online

canadian discount online pharmacy: canadian pharcharmy – list of canadian pharmacies

http://canadadrugs.pro/# synthroid canadian pharmacy

mail order canadian drugs reliable online pharmacy prescriptions from canada without

my canadian drugstore: reliable online canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacieswith no prescription

http://canadadrugs.pro/# canadian generic pharmacy

no prescription drugs canada: online medication – online prescription

canadian prescription drugstore superstore pharmacy online online pharmacy mail order

https://canadadrugs.pro/# canadian online pharmacies

canadian pharmacy rx: canadian prescription filled in the us – canada rx pharmacy

canada mail pharmacy reputable mexican pharmacies canadian pharmaceuticals online

https://canadadrugs.pro/# onlinecanadianpharmacy com

best online drugstore: online drugs – safe online pharmacies in canada

http://canadadrugs.pro/# prescription meds without the prescription

pharmacy express online: prescription online – prescription drug prices

http://canadadrugs.pro/# canada drug online

canadian drug stores: cheap pharmacy – pharmacy canadian

canadian pharmacy direct: most reliable canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy no rx needed

https://canadadrugs.pro/# pharmacy review

canadian pharmacy rx: best online pharmacy stores – canadian pharmacy meds

https://canadadrugs.pro/# canadian pharmaceuticals for usa sales

your discount pharmacy: canadian pharmaceuticals online safe – online canadian pharmacy no prescription needed

https://canadadrugs.pro/# mexican drug pharmacy

levitra from canadian pharmacy: canadian trust pharmacy – online pharmacy mail order

https://canadadrugs.pro/# buy prescription drugs without doctor

https://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# tadalafil without a doctor’s prescription

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexican drugstore online buying prescription drugs in mexico

pet meds without vet prescription canada: certified canadian international pharmacy – canadian pharmacy 24 com

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

buy prescription drugs generic cialis without a doctor prescription ed meds online without doctor prescription

ed medications list: ed meds online without doctor prescription – treatment of ed

https://medicinefromindia.store/# best india pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs purple pharmacy mexico price list

erection pills: pills for ed – ed drug prices

https://canadianinternationalpharmacy.pro/# canadian drug stores

buy prescription drugs from india top 10 online pharmacy in india india pharmacy

https://edpill.cheap/# top erection pills

indian pharmacy online п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india Online medicine home delivery

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

buy prescription drugs from india Online medicine home delivery online shopping pharmacy india

best online pharmacy india: world pharmacy india – mail order pharmacy india

https://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# non prescription erection pills

ed drugs compared best ed pill best over the counter ed pills

http://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# online prescription for ed meds

best online pharmacies in mexico buying prescription drugs in mexico medicine in mexico pharmacies

http://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# buy prescription drugs

Online medicine home delivery п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india reputable indian online pharmacy

http://canadianinternationalpharmacy.pro/# canadian pharmacy 24 com

http://edpill.cheap/# best ed treatment pills

the best ed pills male ed pills ed pills online

http://edpill.cheap/# best ed drugs

ed meds online without doctor prescription generic cialis without a doctor prescription ed meds online without doctor prescription

http://edpill.cheap/# best ed pills

ed meds online without doctor prescription ed pills without doctor prescription non prescription ed pills

https://edpill.cheap/# best ed treatment pills

legal to buy prescription drugs without prescription cialis without a doctor prescription buy prescription drugs

http://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

erectile dysfunction medications erectile dysfunction drug ed meds

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican mail order pharmacies mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

my canadian pharmacy reputable canadian online pharmacies canadian pharmacy com

https://medicinefromindia.store/# indian pharmacies safe

http://edpill.cheap/# what is the best ed pill

reputable indian online pharmacy Online medicine order india pharmacy

http://edpill.cheap/# erectile dysfunction medications

non prescription ed pills best ed pills best ed drugs

medication from mexico pharmacy reputable mexican pharmacies online mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

medication from mexico pharmacy reputable mexican pharmacies online medication from mexico pharmacy

best online pharmacies in mexico pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexican drugstore online mexican mail order pharmacies

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexican pharmacy mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs best online pharmacies in mexico mexico drug stores pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies mexican rx online mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexico drug stores pharmacies purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexico pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican rx online reputable mexican pharmacies online buying prescription drugs in mexico online

medicine in mexico pharmacies purple pharmacy mexico price list pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexican drugstore online mexican rx online mexican pharmacy

medication from mexico pharmacy pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online purple pharmacy mexico price list best online pharmacies in mexico

best online pharmacies in mexico mexican pharmacy п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy mexican drugstore online п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico mexico drug stores pharmacies buying from online mexican pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs best online pharmacies in mexico mexico pharmacy

medicine in mexico pharmacies pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexico pharmacies prescription drugs reputable mexican pharmacies online

medication from mexico pharmacy mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs buying prescription drugs in mexico

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies purple pharmacy mexico price list

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies buying prescription drugs in mexico mexican pharmacy

mexico pharmacy mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexico pharmacy

mexican mail order pharmacies pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican drugstore online mexican rx online

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies medication from mexico pharmacy pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs best online pharmacies in mexico medicine in mexico pharmacies

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexican pharmaceuticals online mexico pharmacy purple pharmacy mexico price list

buying prescription drugs in mexico online pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexican pharmacy best online pharmacies in mexico mexican mail order pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexico drug stores pharmacies mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican mail order pharmacies mexican pharmacy mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexican pharmacy mexican rx online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican drugstore online mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexico drug stores pharmacies pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa buying from online mexican pharmacy pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexican drugstore online mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexico pharmacy mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexico pharmacy

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa best online pharmacies in mexico pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

best online pharmacies in mexico mexican pharmacy mexico pharmacy

mexico pharmacy buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexican pharmacy

medicine in mexico pharmacies mexican pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies

medication from mexico pharmacy mexico pharmacy mexico pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexican drugstore online mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico mexican pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexican pharmaceuticals online mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

buying from online mexican pharmacy buying prescription drugs in mexico medicine in mexico pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy purple pharmacy mexico price list buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexican rx online buying from online mexican pharmacy buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexican rx online mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican pharmacy mexican rx online buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs buying from online mexican pharmacy mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican pharmaceuticals online mexican rx online mexican drugstore online

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexico pharmacies prescription drugs purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican mail order pharmacies purple pharmacy mexico price list mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican mail order pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy medication from mexico pharmacy mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican pharmacy mexican mail order pharmacies best mexican online pharmacies

https://lisinopril.top/# zestril 10 mg price

lasix 40 mg Buy Lasix lasix online

amoxicillin online purchase: where to buy amoxicillin 500mg without prescription – where can i buy amoxicillin without prec

http://lisinopril.top/# lisinopril online pharmacy

lasix uses: Buy Lasix – lasix generic

furosemida Buy Lasix furosemida 40 mg

http://amoxil.cheap/# amoxicillin generic

stromectol australia: ivermectin drug – buy stromectol online

https://buyprednisone.store/# prednisone 30 mg coupon

amoxicillin 30 capsules price amoxicillin 500 mg purchase without prescription amoxicillin brand name

https://buyprednisone.store/# prednisone uk

where to buy amoxicillin 500mg: order amoxicillin online – amoxicillin online without prescription

http://furosemide.guru/# lasix 40 mg

lisinopril 5 mg price lisinopril 10 12.5 mg tablets can you buy lisinopril online

cheapest price for lisinopril: lisinopril 10 mg coupon – prescription drug lisinopril

http://buyprednisone.store/# prednisone 100 mg

cost of ivermectin 1% cream: stromectol cream – ivermectin 500ml

lasix 100 mg Over The Counter Lasix lasix uses

https://amoxil.cheap/# purchase amoxicillin 500 mg

furosemide 100mg: Over The Counter Lasix – furosemide

https://stromectol.fun/# how to buy stromectol

lisinopril cost us lisinopril 200 mg buy 20mg lisinopril

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin 200

stromectol prices: ivermectin pills human – ivermectin price uk

https://amoxil.cheap/# where can i get amoxicillin 500 mg

stromectol covid: stromectol brand – ivermectin 9mg

generic lasix Buy Furosemide buy furosemide online

http://amoxil.cheap/# generic amoxicillin online

ivermectin human: stromectol order – buy stromectol uk

https://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin price usa

lisinopril 3973 where to buy lisinopril 2.5 mg prinivil 5mg tablet

ivermectin cost in usa: ivermectin where to buy – ivermectin 0.5% brand name

https://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin lice

http://buyprednisone.store/# can i buy prednisone online in uk

amoxicillin pharmacy price: amoxicillin buy canada – amoxicillin discount coupon

generic lasix furosemide 100 mg furosemida

https://furosemide.guru/# lasix furosemide 40 mg

http://stromectol.fun/# stromectol price usa

lisinopril cost us: drug lisinopril – generic lisinopril

buy prednisone 40 mg how can i get prednisone prednisone 0.5 mg

http://amoxil.cheap/# order amoxicillin online

http://stromectol.fun/# can you buy stromectol over the counter

where to buy prednisone without prescription: prednisone 30 mg daily – prednisone 60 mg

http://amoxil.cheap/# amoxicillin online purchase

generic prednisone pills buy prednisone online uk prednisone drug costs

lasix 100 mg tablet: Over The Counter Lasix – lasix online

Your writing is like a beacon of light in the darkness, guiding us towards knowledge and understanding. Asheville appreciates your blog!

https://lisinopril.top/# zestril 20 mg price

Your blog is a true masterpiece, crafted with care and passion. We’re proud supporters from Asheville!

furosemide 100 mg: lasix generic name – furosemide 40 mg

http://buyprednisone.store/# prednisone 54899

prinivil cost cost of lisinopril in canada price of lisinopril generic

Your posts never fail to spark curiosity and ignite inspiration. We’re grateful readers from Asheville!

Your posts never fail to spark curiosity and ignite inspiration. We’re grateful readers from Asheville!

Your dedication to your craft shines brightly in every post. Thank you for sharing your passion with us. Asheville is grateful!

Your blog is a true testament to your passion and dedication. We’re proud supporters from Asheville!

http://stromectol.fun/# cost of ivermectin pill

Your posts always leave me feeling enlightened and inspired. Thank you for sharing your knowledge with us. Asheville sends its love!

Thank you for consistently delivering top-notch content. We’re huge fans of your blog here in Asheville!

Thank you for consistently delivering top-notch content. We’re huge fans of your blog here in Asheville!

zestril generic: zestril price in india – lisinopril 3973

Your posts always leave me feeling enlightened and inspired. Thank you for sharing your knowledge with us. Asheville sends its love!

Your words have the power to uplift and inspire. Thank you for sharing your gift with us. Asheville loves your blog!

Your dedication to your craft shines brightly in every post. Thank you for sharing your passion with us. Asheville is grateful!

I just wanted to drop by and say how much I enjoy reading your blog. Asheville adores your work!

Thank you for being a constant source of inspiration through your blog. Asheville is proud to support you!

Your blog is a ray of sunshine in the online world. We’re big fans from Asheville!

http://buyprednisone.store/# prednisone pack

price of ivermectin buy stromectol online stromectol 3 mg dosage

buy amoxicillin 500mg uk: amoxicillin buy online canada – how to get amoxicillin

https://amoxil.cheap/# buy amoxicillin 500mg online

http://buyprednisone.store/# prednisone tablets india

ivermectin 0.5% lotion: ivermectin 50ml – ivermectin where to buy for humans

amoxicillin 500 amoxicillin discount amoxicillin 500 mg without prescription

http://amoxil.cheap/# amoxicillin from canada

lasix tablet: Buy Furosemide – lasix side effects

https://buyprednisone.store/# prednisone best price

buy prednisone without prescription can i buy prednisone online in uk prednisone daily use

https://furosemide.guru/# lasix furosemide 40 mg

lisinopril 20 mg best price: cost for generic lisinopril – lisinopril 10 mg price

https://buyprednisone.store/# can i buy prednisone online in uk

amoxicillin online no prescription: buy amoxicillin 500mg uk – buy amoxicillin online uk

ivermectin 10 ml ivermectin 3mg tablet where to buy ivermectin

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin over the counter

https://indianph.xyz/# india pharmacy mail order

top online pharmacy india

top online pharmacy india top online pharmacy india india pharmacy mail order

https://indianph.com/# online shopping pharmacy india

indian pharmacy paypal

mail order pharmacy india best india pharmacy india pharmacy mail order

http://indianph.xyz/# best online pharmacy india

top 10 online pharmacy in india

indianpharmacy com world pharmacy india indian pharmacy

http://indianph.com/# india pharmacy

best online pharmacy india

http://indianph.xyz/# online pharmacy india

top 10 online pharmacy in india

https://indianph.com/# best india pharmacy

buy medicines online in india

indian pharmacy online pharmacy website india india pharmacy

http://indianph.xyz/# india pharmacy mail order

india online pharmacy

http://indianph.xyz/# top 10 pharmacies in india

indian pharmacy

cipro ciprofloxacin cipro for sale cipro online no prescription in the usa

https://doxycycline.auction/# where can i get doxycycline

buy doxycycline online: doxycycline 100mg online – vibramycin 100 mg

http://doxycycline.auction/# order doxycycline online

cytotec buy online usa: buy cytotec over the counter – п»їcytotec pills online

buy cipro buy cipro online canada ciprofloxacin generic price

https://nolvadex.guru/# tamoxifen postmenopausal

https://diflucan.pro/# diflucan 200 mg tablet

buy cytotec over the counter: buy misoprostol over the counter – Cytotec 200mcg price

buy misoprostol over the counter buy cytotec online fast delivery buy cytotec in usa

https://cytotec24.shop/# order cytotec online

doxy: doxy 200 – doxycycline generic

http://nolvadex.guru/# tamoxifen reviews

п»їcytotec pills online cytotec online buy cytotec pills

http://diflucan.pro/# cost of diflucan prescription in mexico

https://doxycycline.auction/# doxycycline medication

cipro ciprofloxacin: buy cipro online – buy generic ciprofloxacin

how to buy doxycycline online doxycycline vibramycin buy doxycycline online uk

https://doxycycline.auction/# where can i get doxycycline

https://cytotec24.shop/# Abortion pills online

buy cytotec in usa cytotec buy online usa cytotec online

http://doxycycline.auction/# doxycycline

http://cytotec24.shop/# cytotec online

Abortion pills online п»їcytotec pills online п»їcytotec pills online

https://cipro.guru/# ciprofloxacin mail online

https://diflucan.pro/# can you buy diflucan over the counter in australia

cytotec online Misoprostol 200 mg buy online purchase cytotec

http://nolvadex.guru/# tamoxifen endometriosis

purchase cytotec п»їcytotec pills online buy cytotec pills online cheap

https://abelladanger.online/# abella danger video

eva elfie modeli: eva elfie modeli – eva elfie izle

http://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox video

http://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White

Sweetie Fox modeli: sweety fox – Sweetie Fox modeli

http://abelladanger.online/# Abella Danger

https://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie filmleri

https://angelawhite.pro/# ?????? ????

sweeti fox: Sweetie Fox filmleri – sweeti fox

http://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie video

http://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White filmleri

swetie fox: Sweetie Fox – Sweetie Fox

http://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades video

http://angelawhite.pro/# ?????? ????

Angela White izle: abella danger video – abella danger filmleri

https://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White video

https://abelladanger.online/# abella danger izle

lana rhoades modeli: lana rhoades – lana rhoades izle

http://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White

http://abelladanger.online/# abella danger filmleri

https://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades modeli

Angela White filmleri: ?????? ???? – Angela White video

https://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades izle

http://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox izle

Angela White izle: Angela Beyaz modeli – ?????? ????

https://abelladanger.online/# Abella Danger

https://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades modeli

Angela White filmleri: Angela White video – Angela White video

http://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhodes

http://angelawhite.pro/# ?????? ????

swetie fox: sweety fox – Sweetie Fox filmleri

http://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White

https://abelladanger.online/# abella danger video

http://sweetiefox.online/# sweeti fox

https://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades filmleri

eva elfie: eva elfie izle – eva elfie

http://sweetiefox.online/# swetie fox

https://abelladanger.online/# Abella Danger

eva elfie modeli: eva elfie izle – eva elfie modeli

http://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie filmleri

https://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie filmleri

eva elfie modeli: eva elfie – eva elfie

lana rhoades unleashed: lana rhoades hot – lana rhoades solo

http://evaelfie.site/# eva elfie hot

http://evaelfie.site/# eva elfie hot

mia malkova videos: mia malkova – mia malkova

http://sweetiefox.pro/# sweetie fox cosplay

lana rhoades: lana rhoades solo – lana rhoades hot

http://lanarhoades.pro/# lana rhoades full video

ph sweetie fox: sweetie fox video – sweetie fox video

https://sweetiefox.pro/# fox sweetie

eva elfie photo: eva elfie hot – eva elfie

lana rhoades boyfriend: lana rhoades unleashed – lana rhoades boyfriend

저희는 구글 계정 판매 전문 회사입니다.우리의 구글 계정은 이메일, 문서, 캘리더, 클라우드 저장 등의 기능을 포함한 포괄적인 디지털 솔루션을 제공합니다.구글 계정을 통해 우리는 사용자에게 효율적인 협업 플랫품을 제공하여 개인과 팀이 일과 삶을 더 스마트하게 관리할 수 있도록 지원합니다.

http://miamalkova.life/# mia malkova only fans

mia malkova hd: mia malkova movie – mia malkova only fans

http://sweetiefox.pro/# sweetie fox full video

lana rhoades hot: lana rhoades solo – lana rhoades hot

http://sweetiefox.pro/# sweetie fox cosplay

sweetie fox full video: sweetie fox cosplay – sweetie fox cosplay

http://lanarhoades.pro/# lana rhoades full video

eva elfie full videos: eva elfie hot – eva elfie

http://sweetiefox.pro/# fox sweetie

sweetie fox: fox sweetie – fox sweetie

eva elfie new video: eva elfie – eva elfie videos

http://lanarhoades.pro/# lana rhoades videos

https://evaelfie.site/# eva elfie

비아그라를 구매하려면 알레르기 반응을 고려해야 합니다. 비아그라 주요 성분에 알레르기가 있을 수 있으므로, 의사와 상의하고 알레르기 반응 증상을 주시해야 합니다

jogar aviator: aviator mz – jogar aviator

http://aviatormalawi.online/# aviator

aviator sportybet ghana: aviator bet – aviator sportybet ghana

http://pinupcassino.pro/# pin up bet

aviator: como jogar aviator em moçambique – aviator online

https://pinupcassino.pro/# pin-up casino entrar

aviator game bet: play aviator – aviator betting game

aviator pin up: jogar aviator online – aviator jogo

pin up cassino online: pin up – pin-up casino login

http://aviatorjogar.online/# aviator game

th of India 문의하기rather than 문의하기the industri문의하기al w

aviator game: play aviator – aviator game

네이버 플랫품에서 사용되는 아이디를 판매하고 있습니다. 네이버 아이디 판매 가격은 1,000원이고 30개부터 구매 가능합니다.

aviator bet malawi: aviator game online – aviator bet malawi

jogar aviator: jogar aviator – aviator online

aviator bet: aviator jogo – aviator pin up

aviator: aviator bet malawi – aviator malawi

aviator: jogar aviator – como jogar aviator em moçambique

aviator oyunu: aviator sinyal hilesi – aviator hilesi

pin-up casino: pin-up cassino – pin up casino

zithromax online: buy zithromax 1000 mg online – zithromax without prescription

aviator game bet: aviator sportybet ghana – aviator betting game

como jogar aviator em moçambique: jogar aviator – como jogar aviator

jogar aviator online: aviator bet – pin up aviator

zithromax cost uk – https://azithromycin.pro/zithromax-walmart-cost.html zithromax online pharmacy canada

Repository b비아그라 약국y the Nation비아그라 약국al Biodivers비아그라 약국ity

Online medicine order: online pharmacy in india – best online pharmacy india indianpharm.store

best canadian pharmacy online: Canada pharmacy online – safe online pharmacies in canada canadianpharm.store

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: Mexico pharmacy price list – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexicanpharm.shop

http://indianpharm24.shop/# legitimate online pharmacies india indianpharm.store

https://canadianpharmlk.shop/# canadian pharmacy meds review canadianpharm.store

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: Medicines Mexico – best online pharmacies in mexico mexicanpharm.shop

http://canadianpharmlk.shop/# canadian pharmacy 365 canadianpharm.store

https://canadianpharmlk.shop/# canadapharmacyonline legit canadianpharm.store

http://mexicanpharm24.com/# mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexicanpharm.shop

india pharmacy: Generic Medicine India to USA – Online medicine order indianpharm.store

http://indianpharm24.com/# Online medicine order indianpharm.store

http://indianpharm24.com/# Online medicine order indianpharm.store

ordering drugs from canada: My Canadian pharmacy – canadianpharmacymeds com canadianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm24.com/# best mexican online pharmacies mexicanpharm.shop

CSIR-CIMAP h비아그라 storeas played an비아그라 store important r비아그라 storeole

http://canadianpharmlk.shop/# canadian pharmacy 365 canadianpharm.store

https://indianpharm24.com/# pharmacy website india indianpharm.store

pharmacy website india: india pharmacy – indianpharmacy com indianpharm.store

https://canadianpharmlk.com/# canadian drug prices canadianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm24.shop/# reputable mexican pharmacies online mexicanpharm.shop

http://indianpharm24.com/# top 10 pharmacies in india indianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm24.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies mexicanpharm.shop

https://canadianpharmlk.com/# certified canadian pharmacy canadianpharm.store

네이버 최고급 프리미업 아이디 판매, 네이버 아이디 구매사이트,네이버 비실명계정 구매사이트.

amoxicillin generic: cheap amoxicillin 500mg – where can i get amoxicillin

prednisone 10 mg over the counter: prednisone 5mg coupon – prednisone 20mg

http://prednisonest.pro/# how much is prednisone 5mg

cost of clomid prices: order generic clomid tablets – where can i buy cheap clomid

http://prednisonest.pro/# prednisone 20 mg tablet price

how to get clomid: clomid 50mg price – where to buy generic clomid without rx

idering aest정품비아그라hetics and i정품비아그라ts ability t정품비아그라o be

can i get clomid prices: alternative to clomid – clomid prices

prednisone 30 mg: prednisone 10 mg tablet – prednisone 10mg

https://clomidst.pro/# how to buy cheap clomid without prescription

how to get clomid: can you get generic clomid without insurance – can i purchase cheap clomid without a prescription

prednisone 40mg: buy prednisone online canada – prednisone 20mg online

https://clomidst.pro/# where can i buy clomid without a prescription

where can you get amoxicillin: amoxicillin-clavulanate – amoxicillin without a doctors prescription

where buy generic clomid: clomid vs testosterone – get generic clomid without dr prescription

prednisone in canada: prednisone without prescription.net – prednisone purchase online

https://amoxilst.pro/# amoxicillin over counter

how much is prednisone 10 mg: what is the lowest dose of prednisone you can take – prednisone 20

where can i buy cheap clomid without insurance: get clomid without a prescription – cost of generic clomid without insurance

quality prescription drugs canada: canada pharmacy without prescription – canada mail order prescription

http://onlinepharmacy.cheap/# cheapest pharmacy prescription drugs

buy medications online without prescription: buy prescription drugs online without – buy drugs online no prescription

medications online without prescriptions: online pharmacy without prescription – best online pharmacy no prescription

https://onlinepharmacy.cheap/# drugstore com online pharmacy prescription drugs

buy ed pills: erectile dysfunction meds online – ed doctor online

buying prescription drugs online without a prescription: best online prescription – online pharmacy not requiring prescription

cheapest erectile dysfunction pills: ed treatments online – top rated ed pills

http://edpills.guru/# cheap boner pills

no prescription medicines: buying drugs without prescription – canada prescription drugs online

no prescription online pharmacy: best online pharmacy no prescription – buy pain meds online without prescription

online ed drugs: cheap ed pills – best online ed medication

https://pharmnoprescription.pro/# best online pharmacy without prescriptions

cheapest prescription pharmacy: Online pharmacy USA – online pharmacy without prescription

https://pharmnoprescription.pro/# online pharmacy that does not require a prescription

online pharmacy no prescription: online doctor prescription canada – medication online without prescription

canadian and international prescription service: mexican pharmacy no prescription – can i buy prescription drugs in canada

The technolo비아그라 100mg 2판 16정gy for the f비아그라 100mg 2판 16정abrication o비아그라 100mg 2판 16정f “L

online ed pills: online erectile dysfunction prescription – buy ed pills

100%정품비아그라,약국에서 판매되는 제품과 동일한 제품만 취급합니다.

100%정품비아그라,약국에서 판매되는 제품과 동일한 제품만 취급합니다.

buy medicines online in india: online shopping pharmacy india – top 10 pharmacies in india

mexico drug stores pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – medicine in mexico pharmacies

V Raman etc.시알리스 20mg 4판 16정.) and young시알리스 20mg 4판 16정 scientist (시알리스 20mg 4판 16정CSIR

http://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# pharmacy no prescription

buying prescription medications online: canadian prescription – order prescription drugs online without doctor

canada pharmacy online no prescription: quality prescription drugs canada – buy drugs online no prescription

https://indianpharm.shop/# reputable indian online pharmacy

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy prices – vipps canadian pharmacy

https://indianpharm.shop/# top online pharmacy india

Online medicine order: reputable indian pharmacies – reputable indian online pharmacy

canadian 24 hour pharmacy: canadian pharmacy 24h com – canadian pharmacy scam

canada mail order prescription: no prescription online pharmacies – online drugs without prescription

https://indianpharm.shop/# top 10 pharmacies in india

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – buying prescription drugs in mexico

medications online without prescription: canadian pharmacy without a prescription – online pharmacies without prescription

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: medicine in mexico pharmacies – best online pharmacies in mexico

http://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# ordering prescription drugs from canada

비아그라 100mg 1+1 2판(8정) 9,9000원 비아그라는 Prizer라는 제약회사에서 생산하는 발기 부전 치료제로,실데나필이라는 주요 성분을 포함하고 있습니다. 이 약물은 혈관을 확장시켜 성기에 더 많은 혈액을 유입시ㅣ켜 발기를 도와주는 효과를 가지고 있습니다.

canadian world pharmacy: is canadian pharmacy legit – canadian neighbor pharmacy

discount prescription drugs canada: mexico online pharmacy prescription drugs – best online pharmacy that does not require a prescription in india

https://indianpharm.shop/# indian pharmacies safe

indian pharmacy online: pharmacy website india – mail order pharmacy india

reputable indian online pharmacy: online shopping pharmacy india – buy prescription drugs from india

https://mexicanpharm.online/# best online pharmacies in mexico

how to order prescription drugs from canada: non prescription canadian pharmacy – online meds no prescription

indianpharmacy com: india online pharmacy – india pharmacy mail order

http://canadianpharm.guru/# reddit canadian pharmacy

buy prescription drugs from india: Online medicine home delivery – legitimate online pharmacies india

india pharmacy: india pharmacy – reputable indian online pharmacy

is an exampl비아그라 유통기한e of transla비아그라 유통기한tion of indu비아그라 유통기한stri

canadian pharmacy no scripts: safe online pharmacies in canada – thecanadianpharmacy

https://mexicanpharm.online/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

canadian neighbor pharmacy: canadian pharmacy phone number – best canadian online pharmacy

india online pharmacy: buy prescription drugs from india – india pharmacy mail order

http://indianpharm.shop/# india pharmacy mail order

best india pharmacy: online pharmacy india – mail order pharmacy india

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: medication from mexico pharmacy – mexican pharmacy

indian pharmacies safe: online shopping pharmacy india – indian pharmacy

http://mexicanpharm.online/# mexican mail order pharmacies

reputable indian pharmacies: india online pharmacy – reputable indian online pharmacy

best canadian pharmacy online: buy prescription drugs from canada cheap – canadian pharmacy near me

medication from mexico pharmacy: medication from mexico pharmacy – mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://canadianpharm.guru/# recommended canadian pharmacies

cheap canadian pharmacy online: canadian world pharmacy – pet meds without vet prescription canada

http://mexicanpharm.online/# mexican pharmacy

reputable indian online pharmacy: reputable indian pharmacies – best online pharmacy india

medication canadian pharmacy: canada rx pharmacy world – pharmacy canadian superstore

purple pharmacy mexico price list: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexican pharmacy

http://mexicanpharm.online/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

canadian pharmacy 365: canadian pharmacies compare – canada drugs online review

reputable mexican pharmacies online: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – mexican drugstore online

https://gatesofolympus.auction/# gates of olympus sirlari

slot siteleri bonus veren: en iyi slot siteleri – casino slot siteleri

http://pinupgiris.fun/# pin-up casino

gates of olympus slot: gates of olympus demo turkce oyna – gates of olympus

https://sweetbonanza.bid/# sweet bonanza mostbet

out at the s비아그라 먹으면 안되는 사람ite as well.비아그라 먹으면 안되는 사람 This techno비아그라 먹으면 안되는 사람logy

http://slotsiteleri.guru/# slot siteleri bonus veren

aviator hilesi ucretsiz: aviator sinyal hilesi apk – aviator oyna 20 tl

http://gatesofolympus.auction/# gates of olympus giris

deneme bonusu veren siteler: guvenilir slot siteleri 2024 – deneme bonusu veren slot siteleri

http://pinupgiris.fun/# pin up casino güncel giris

https://sweetbonanza.bid/# sweet bonanza yasal site

gates of olympus giris: gates of olympus hilesi – gates of olympus giris

http://sweetbonanza.bid/# slot oyunlari

pin up 7/24 giris: pin up guncel giris – pin up giris

http://slotsiteleri.guru/# en iyi slot siteleri 2024

https://pinupgiris.fun/# pin up güncel giris

gates of olympus guncel: gates of olympus max win – gates of olympus taktik

https://pinupgiris.fun/# pin up casino güncel giris

gates of olympus demo oyna: gates of olympus max win – gates of olympus hilesi

https://sweetbonanza.bid/# sweet bonanza demo

http://slotsiteleri.guru/# en çok kazandiran slot siteleri

slot bahis siteleri: canl? slot siteleri – canl? slot siteleri

http://pinupgiris.fun/# pin up indir

gates of olympus s?rlar?: gates of olympus demo – gates of olympus guncel

https://slotsiteleri.guru/# en yeni slot siteleri

네이버 최고급 프리미업 아이디 판매, 네이버 아이디 판매 사이트,네이버 비실명계정 구매사이트.

gates of olympus demo free spin: gates of olympus max win – gates of olympus nas?l para kazanilir

http://pinupgiris.fun/# pin-up bonanza

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies Online Pharmacies in Mexico mexican rx online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican pharmacy mexican pharmaceuticals online

ns and citat비아그라 약국ions indicat비아그라 약국e the global비아그라 약국 rel

top 10 online pharmacy in india Cheapest online pharmacy online shopping pharmacy india

buying prescription drugs in mexico mexico pharmacy purple pharmacy mexico price list

medication canadian pharmacy: Large Selection of Medications – canadian pharmacy scam

online pharmacy canada: Certified Canadian Pharmacy – best canadian online pharmacy

canada rx pharmacy Licensed Canadian Pharmacy canadian family pharmacy

canadian pharmacy online reviews: Certified Canadian Pharmacy – rate canadian pharmacies

best mexican online pharmacies: mexican pharmacy – purple pharmacy mexico price list

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican pharmacy – mexican rx online

india pharmacy mail order indian pharmacy Online medicine home delivery

reputable indian online pharmacy: Generic Medicine India to USA – Online medicine home delivery

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: Online Pharmacies in Mexico – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

canadian pharmacies comparison canadian pharmacy 24 canadian drug stores

mexico drug stores pharmacies: Mexican Pharmacy Online – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

online pharmacy india: indian pharmacy – world pharmacy india

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican pharmacy – mexico pharmacy

medication from mexico pharmacy mexican pharmacy purple pharmacy mexico price list

online canadian pharmacy reviews pills now even cheaper canadian drug stores

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican pharmacy – buying from online mexican pharmacy

canadian neighbor pharmacy Large Selection of Medications best canadian online pharmacy reviews

mail order pharmacy india: Cheapest online pharmacy – world pharmacy india

http://prednisoneall.com/# prednisone for sale

http://prednisoneall.com/# prednisone 2 mg daily

amoxicillin online pharmacy amoxicillin 500mg buy cheap amoxicillin

http://prednisoneall.com/# prednisone 5 mg cheapest

white efflor비아그라파는곳escence, cra비아그라파는곳cking, melt-비아그라파는곳stic

https://amoxilall.shop/# medicine amoxicillin 500

zithromax zithromax 500 zithromax generic price

https://amoxilall.shop/# amoxicillin 500 coupon

where can i buy amoxocillin prescription for amoxicillin can i buy amoxicillin over the counter

http://zithromaxall.shop/# cheap zithromax pills

http://zithromaxall.shop/# order zithromax over the counter

online order prednisone 10mg prednisone 50 mg buy prednisone pharmacy

http://amoxilall.shop/# over the counter amoxicillin

http://zithromaxall.com/# zithromax 250 mg pill

http://amoxilall.com/# buy amoxicillin online without prescription

can i order cheap clomid without a prescription can you get generic clomid without insurance cost cheap clomid no prescription

https://amoxilall.shop/# how to buy amoxycillin

https://clomidall.shop/# where can i get clomid without rx

http://zithromaxall.com/# zithromax 500 price

zithromax capsules buy zithromax no prescription zithromax antibiotic without prescription

http://zithromaxall.com/# where can i buy zithromax uk

네이버 아이디 구매 네이버 검색: 네이버 검색 엔진은 웹에서 정보를 검색하는 데 사용됩니다. 사용자가 검색어를 입력하면 웹 페이지, 이미지, 블로그, 뉴스 등 다양한 결과를 제공합니다.

cheapest viagra best price on viagra Viagra online price

sildenafil over the counter: best price on viagra – over the counter sildenafil

buy kamagra online usa: Kamagra gel – Kamagra 100mg price

Buy Tadalafil 10mg: cheapest cialis – Generic Cialis price

Kamagra 100mg Kamagra Iq Kamagra tablets

Buy Cialis online: Buy Cialis online – Buy Tadalafil 20mg

lea, Gladiol비아그라 구매us, and Cann비아그라 구매a by the Pro비아그라 구매tect

buy viagra here: best price on viagra – Sildenafil Citrate Tablets 100mg

Generic Cialis price Buy Cialis online Generic Tadalafil 20mg price

cheap kamagra: kamagra best price – super kamagra

buy Kamagra Sildenafil Oral Jelly cheap kamagra

cheap viagra: cheapest viagra – cheap viagra

Tadalafil price: Buy Cialis online – Cialis 20mg price

http://kamagraiq.com/# Kamagra 100mg price

buy Viagra online cheapest viagra buy Viagra online

buy kamagra online usa: Kamagra Iq – Kamagra 100mg price

http://tadalafiliq.shop/# Buy Tadalafil 20mg

super kamagra: Sildenafil Oral Jelly – super kamagra

Cialis 20mg price in USA cialis best price Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription

Cheap generic Viagra online: cheapest viagra – best price for viagra 100mg

https://sildenafiliq.xyz/# Generic Viagra for sale

Buy Tadalafil 10mg: tadalafil iq – Buy Tadalafil 20mg

sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra kamagra best price sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra

https://sildenafiliq.xyz/# Sildenafil 100mg price

buy Kamagra: Kamagra 100mg price – Kamagra tablets

sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra kamagra best price sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra

Kamagra 100mg price: kamagra best price – Kamagra Oral Jelly

https://tadalafiliq.shop/# п»їcialis generic

sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra: sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra – buy Kamagra

sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra kamagra best price Kamagra 100mg price

https://sildenafiliq.com/# Cheap Viagra 100mg

Buy Tadalafil 5mg: cialis without a doctor prescription – Buy Tadalafil 10mg

Kamagra 100mg price Sildenafil Oral Jelly Kamagra tablets

canadian pharmacy meds Pharmacies in Canada that ship to the US canadian pharmacy price checker

https://canadianpharmgrx.com/# legitimate canadian pharmacy

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexican pharmacy purple pharmacy mexico price list

Online medicine order best online pharmacy india indian pharmacy online

http://canadianpharmgrx.com/# canadian online drugstore

indian pharmacy indian pharmacy delivery top 10 online pharmacy in india

https://canadianpharmgrx.xyz/# trusted canadian pharmacy

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs Pills from Mexican Pharmacy buying prescription drugs in mexico online

https://indianpharmgrx.com/# pharmacy website india

https://canadianpharmgrx.com/# canada pharmacy reviews

mexican mail order pharmacies Pills from Mexican Pharmacy pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

https://mexicanpharmgrx.shop/# mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

pharmacy website india Generic Medicine India to USA reputable indian pharmacies

http://indianpharmgrx.com/# indian pharmacies safe

buying from online mexican pharmacy online pharmacy in Mexico mexico drug stores pharmacies

days in the 비아그라구매farms and 16비아그라구매2 lakh man-d비아그라구매ays

mexican mail order pharmacies Pills from Mexican Pharmacy mexico pharmacy

http://mexicanpharmgrx.com/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

http://canadianpharmgrx.xyz/# canadian neighbor pharmacy

https://canadianpharmgrx.com/# canadian pharmacy 365

nolvadex online: does tamoxifen make you tired – does tamoxifen cause bone loss

buy diflucan medicarions buy diflucan where to buy diflucan 1

doxycycline online: where can i get doxycycline – buy doxycycline 100mg

tamoxifen vs raloxifene: nolvadex gynecomastia – nolvadex 20mg

buy doxycycline online how to buy doxycycline online doxycycline prices

buy cytotec over the counter: buy misoprostol over the counter – buy cytotec

diflucan without get a prescription online medicine diflucan price diflucan 300 mg

nd: Biogeoch비아그라효능emical cycli비아그라효능ng of major 비아그라효능(car

buy diflucan online usa: can you purchase diflucan – 150 mg diflucan online

네이버 아이디 판매 네이버는 다양한 온라인 서비스와 웹사이트를 제공하며, 대한민국을 중심으로 아시아와 기타 지역에서 많은 이용자들에게 서비스를 제공하고 있습니다. 네이버의 주요 서비스 종류는 다음과 같습니다

doxycycline hyc: doxycycline 100mg capsules – buy cheap doxycycline online

cytotec pills buy online cytotec pills buy online buy misoprostol over the counter

tamoxifen bone density: tamoxifen premenopausal – dcis tamoxifen

nolvadex d: aromatase inhibitors tamoxifen – tamoxifen blood clots

order diflucan online cheap where can you get diflucan buying diflucan

does tamoxifen cause bone loss: cost of tamoxifen – alternative to tamoxifen

tamoxifen joint pain: tamoxifen rash pictures – tamoxifenworld

t only its u비아그라구입tmost pride 비아그라구입but also its비아그라구입 act

cipro for sale buy cipro cipro ciprofloxacin

tamoxifen 20 mg tablet: tamoxifen side effects forum – tamoxifen pill

art code, bo비아그라가격tanical name비아그라가격, family, Ay비아그라가격urve

tamoxifen endometriosis tamoxifen endometriosis tamoxifen dose

doxycycline hyc: doxycycline 50mg – buy generic doxycycline

vibramycin 100 mg: buy generic doxycycline – doxycycline mono

online doxycycline generic doxycycline buy doxycycline online without prescription

buy doxycycline online without prescription: doxycycline 100mg price – doxycycline 50 mg

tamoxifen endometrium arimidex vs tamoxifen bodybuilding tamoxifen depression

Cytotec 200mcg price: cytotec buy online usa – buy cytotec online

generic zithromax over the counter order zithromax without prescription buy zithromax without presc

where can i buy generic clomid without dr prescription: buying generic clomid – where can i get generic clomid pills

buy prednisone 40 mg prednisone without prescription 10mg prednisone 20mg

where can i get amoxicillin: can we buy amoxcillin 500mg on ebay without prescription – can you purchase amoxicillin online

buy prednisone online canada: prednisone rx coupon – where to buy prednisone in canada

zithromax tablets zithromax 1000 mg pills zithromax online paypal

http://clomida.pro/# can you buy generic clomid without a prescription

cost of ivermectin 1% cream: ivermectin price comparison – where to buy stromectol

stromectol 3mg tablets ivermectin canada ivermectin tablets uk

https://prednisonea.store/# prednisone 10mg

875 mg amoxicillin cost: amoxicillin 500mg over the counter – cheap amoxicillin 500mg

zithromax buy online: can you buy zithromax over the counter in mexico – where to get zithromax

http://prednisonea.store/# buy prednisone online canada

prednisone 5 50mg tablet price prednisone 2.5 mg 50 mg prednisone tablet

ivermectin price: ivermectin gel – stromectol nz

https://clomida.pro/# can you buy clomid prices

order zithromax without prescription: zithromax 500 – zithromax 500 mg for sale

cheap ed medicine best online ed pills cheap ed pills

meds online no prescription: no prescription needed pharmacy – online pharmacy that does not require a prescription

https://edpill.top/# erectile dysfunction online prescription

pharmacy discount coupons online pharmacy no prescription pharmacy coupons

http://edpill.top/# buy ed meds

ed medicines: cheapest ed online – low cost ed meds

http://edpill.top/# generic ed meds online

online pharmacy no prescription needed legal online pharmacy coupon code canadian pharmacy world coupon

as been desi비아그라 구매gnated as a 비아그라 구매Living Natio비아그라 구매nal

cheapest prescription pharmacy: pharmacy discount coupons – canada pharmacy not requiring prescription

https://medicationnoprescription.pro/# buying prescription drugs from canada online

international pharmacy no prescription no prescription needed pharmacy pharmacy without prescription

http://edpill.top/# best online ed treatment

cheap erection pills: generic ed meds online – generic ed meds online

reputable online pharmacy no prescription mail order prescription drugs from canada online pharmacy prescription

http://medicationnoprescription.pro/# mexican pharmacy no prescription

https://casinvietnam.com/# game c? b?c online uy tin

casino tr?c tuy?n casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam danh bai tr?c tuy?n

비아그라는 처방전이 필요한 약물로 분류되어 있기 때문에, 올바른 절차를 따라 구매해야 합니다. 여기서는 비아그라를 구매하는 올바른 방법에 대해 알아보겠습니다.

비아그라 구매방법

I’m gone to say to my little brother, that he should also go to see this weblog on regular basis to get updated from most recent information.

casino tr?c tuy?n uy tin casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam game c? b?c online uy tin

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam: choi casino tr?c tuy?n trên di?n tho?i – dánh bài tr?c tuy?n

choi casino tr?c tuy?n trên di?n tho?i: dánh bài tr?c tuy?n – web c? b?c online uy tín

web c? b?c online uy tín: dánh bài tr?c tuy?n – casino tr?c tuy?n uy tín

ves which pr비아그라 구매방법ovided a cru비아그라 구매방법cial base fr비아그라 구매방법om w

choi casino tr?c tuy?n trên di?n tho?i: web c? b?c online uy tín – web c? b?c online uy tín

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam: game c? b?c online uy tín – game c? b?c online uy tín

http://casinvietnam.com/# casino tr?c tuy?n

game c? b?c online uy tin casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam danh bai tr?c tuy?n

casino online uy tín: dánh bài tr?c tuy?n – casino online uy tín

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam casino tr?c tuy?n

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam: choi casino tr?c tuy?n trên di?n tho?i – casino online uy tín

http://casinvietnam.shop/# danh bai tr?c tuy?n

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam: web c? b?c online uy tín – casino online uy tín

http://casinvietnam.shop/# casino tr?c tuy?n uy tin

game c? b?c online uy tin casino online uy tin danh bai tr?c tuy?n

casino tr?c tuy?n vi?t nam: web c? b?c online uy tín – casino tr?c tuy?n uy tín

https://canadaph24.pro/# canadian pharmacy world reviews

purple pharmacy mexico price list Mexican Pharmacy Online mexican pharmacy

http://mexicoph24.life/# medication from mexico pharmacy

best india pharmacy Generic Medicine India to USA top online pharmacy india

https://indiaph24.store/# india pharmacy

best online canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacies canada pharmacy online

http://mexicoph24.life/# best mexican online pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico Mexican Pharmacy Online mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

https://canadaph24.pro/# escrow pharmacy canada

mexico pharmacy: Mexican Pharmacy Online – reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican mail order pharmacies Mexican Pharmacy Online medication from mexico pharmacy

http://canadaph24.pro/# canada drugs online review

canada drugs Prescription Drugs from Canada best canadian online pharmacy

, research i비아그라 구매 사이트s being carr비아그라 구매 사이트ied out on n비아그라 구매 사이트ew g

http://mexicoph24.life/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

top online pharmacy india indian pharmacy fast delivery india pharmacy mail order

top 10 pharmacies in india indian pharmacy india online pharmacy

오프라인 구매는 현지 약국을 방문하거나 헬스케어 전문가와 직접 상담하는 등 전통적인 경로로 비아그라를 구매하는 것을 말합니다.

https://canadaph24.pro/# canada pharmacy world

online pharmacy india Cheapest online pharmacy best india pharmacy

http://mexicoph24.life/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

canada drugstore pharmacy rx Certified Canadian Pharmacies canadian online drugstore

https://mexicoph24.life/# mexican pharmacy

mexican rx online Online Pharmacies in Mexico buying prescription drugs in mexico

nges and urb비아그라 구매 사이트anization on비아그라 구매 사이트 the genesis비아그라 구매 사이트 and

https://mexicoph24.life/# mexican drugstore online

canadian pharmacy mall Certified Canadian Pharmacies online canadian drugstore

http://canadaph24.pro/# canadian pharmacy 24

top 10 online pharmacy in india indian pharmacy indian pharmacy paypal

https://indiaph24.store/# india pharmacy mail order

canadian pharmacy online Large Selection of Medications from Canada canada drugs online review

http://indiaph24.store/# top 10 online pharmacy in india

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexican pharmacy purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://indiaph24.store/# top 10 pharmacies in india

best online pharmacy india indian pharmacy fast delivery indianpharmacy com

https://canadaph24.pro/# canada drugs online review

medication canadian pharmacy Certified Canadian Pharmacies prescription drugs canada buy online

https://mexicoph24.life/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

india pharmacy mail order Generic Medicine India to USA india online pharmacy

trusted canadian pharmacy Certified Canadian Pharmacies canadian pharmacy 1 internet online drugstore

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa Mexican Pharmacy Online medicine in mexico pharmacies

http://mexicoph24.life/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

canadian pharmacy Certified Canadian Pharmacies pharmacy canadian

http://mexicoph24.life/# mexican mail order pharmacies

http://indiaph24.store/# india online pharmacy

mexican rx online cheapest mexico drugs mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://mexicoph24.life/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

india pharmacy mail order Generic Medicine India to USA top online pharmacy india

http://indiaph24.store/# top 10 pharmacies in india

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexico pharmacy mexican mail order pharmacies

https://canadaph24.pro/# medication canadian pharmacy

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://indiaph24.store/# indian pharmacy online

india pharmacy mail order buy medicines from India buy prescription drugs from india

http://indiaph24.store/# Online medicine order

mexican mail order pharmacies mexico pharmacy mexican drugstore online

https://canadaph24.pro/# canada rx pharmacy

ral Calcutta비아그라 먹으면 커지나요. A group of비아그라 먹으면 커지나요 highly tale비아그라 먹으면 커지나요nted

http://indiaph24.store/# top 10 pharmacies in india

reputable indian pharmacies buy medicines from India india pharmacy

http://mexicoph24.life/# best online pharmacies in mexico

top online pharmacy india buy medicines from India indian pharmacies safe

http://indiaph24.store/# cheapest online pharmacy india

india online pharmacy best online pharmacy india reputable indian pharmacies

http://indiaph24.store/# online shopping pharmacy india

mexican rx online best online pharmacies in mexico mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://indiaph24.store/# buy prescription drugs from india

https://mexicoph24.life/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

online shopping pharmacy india indian pharmacy fast delivery mail order pharmacy india

https://mexicoph24.life/# best mexican online pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies Online Pharmacies in Mexico mexican pharmacy

https://indiaph24.store/# indianpharmacy com

M) and model비아그라 먹으면 오래하나요 simulated (비아그라 먹으면 오래하나요3 experiment비아그라 먹으면 오래하나요s) r

buying prescription drugs in mexico cheapest mexico drugs reputable mexican pharmacies online

https://canadaph24.pro/# canada drugs online review

canadian pharmacy 24 com Prescription Drugs from Canada buying from canadian pharmacies

http://mexicoph24.life/# mexican rx online

top 10 online pharmacy in india indian pharmacy fast delivery online pharmacy india

https://canadaph24.pro/# canadian pharmacy 24

https://indiaph24.store/# pharmacy website india

indian pharmacies safe Generic Medicine India to USA pharmacy website india

reputable indian pharmacies Generic Medicine India to USA п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

lunteers fro여성용 비아그라 구매m members of여성용 비아그라 구매 the staff o여성용 비아그라 구매f th

http://indiaph24.store/# indianpharmacy com

http://canadaph24.pro/# my canadian pharmacy reviews

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexican drugstore online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: Mexican Pharmacy Online – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

prinivil medication lisinopril 10 mg no prescription cost of lisinopril 30 mg

Abortion pills online: cytotec pills online – cytotec buy online usa

tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention: tamoxifen lawsuit – arimidex vs tamoxifen bodybuilding

tamoxifen for sale tamoxifen hot flashes tamoxifen and uterine thickening

ciprofloxacin buy cipro ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet price

http://nolvadex.life/# tamoxifen lawsuit

http://cytotec.club/# buy cytotec

cost of propecia: buying generic propecia pills – propecia medication

buy cipro cheap: buy cipro cheap – cipro pharmacy

buy propecia for sale buying propecia without insurance cheap propecia prices

https://ciprofloxacin.tech/# purchase cipro

https://finasteride.store/# buy cheap propecia pill

lisinopril tablet 40 mg: drug lisinopril – lisinopril 2.5 mg medicine

medicine lisinopril 10 mg lisinopril canada otc lisinopril

buy cytotec cytotec online buy cytotec pills online cheap

http://nolvadex.life/# raloxifene vs tamoxifen

cipro buy cipro online canada buy cipro cheap

술이 몸에 미치는 영향과 비아그라의 의도된 효과를 이해함으로써 자신의 성적 경험을 향상시키는 책임감 있는 선택을 할 수 있습니다. 비아그라를 복용하면서 술을 마시는 것을 선택했다면, 적당히 하고 몸의 반응을 염두에 두어야 합니다.

술먹고 비아그라 먹으면

buy cytotec online fast delivery Misoprostol 200 mg buy online buy cytotec pills

Cytotec 200mcg price: order cytotec online – cytotec buy online usa

buy cipro online: ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet price – ciprofloxacin order online

https://ciprofloxacin.tech/# buy ciprofloxacin

buying cheap propecia online cost generic propecia buy propecia no prescription

http://finasteride.store/# cost of propecia online

buy cipro online canada buy cipro cheap ciprofloxacin generic price

tamoxifen chemo: tamoxifen reviews – tamoxifen endometrium

cipro for sale ciprofloxacin 500mg buy online buy cipro

http://nolvadex.life/# how to prevent hair loss while on tamoxifen

cipro online no prescription in the usa buy cipro online canada buy cipro

https://lisinopril.network/# lisinopril tabs

cytotec pills buy online: Misoprostol 200 mg buy online – buy cytotec in usa

is nolvadex legal: nolvadex generic – nolvadex only pct

tamoxifen reviews natural alternatives to tamoxifen tamoxifen breast cancer

zestril price uk zestril 20 mg price lisinopril 40mg

https://finasteride.store/# buy propecia without dr prescription

http://ciprofloxacin.tech/# buy ciprofloxacin

zestoretic coupon: cost of generic lisinopril – zestril drug

Misoprostol 200 mg buy online: order cytotec online – buy cytotec pills

cytotec abortion pill buy misoprostol over the counter buy cytotec over the counter

http://finasteride.store/# cost of propecia prices

https://finasteride.store/# propecia generic

buy cytotec online: cytotec pills buy online – cytotec abortion pill

lisinopril 25 cost of lisinopril 40 mg prinivil brand name

buy cytotec online fast delivery: buy cytotec in usa – buy cytotec pills

cost of generic propecia tablets order cheap propecia tablets cost propecia price

https://cytotec.club/# order cytotec online

https://ciprofloxacin.tech/# cipro ciprofloxacin

п»їcytotec pills online cytotec online buy misoprostol over the counter

lisinopril for sale: lisinopril 20 mg buy – zestril 20 mg cost

clomid nolvadex tamoxifen chemo nolvadex pills

cytotec pills online: cytotec buy online usa – cytotec abortion pill

http://nolvadex.life/# nolvadex generic

https://finasteride.store/# cost of propecia without dr prescription

order propecia without rx buy cheap propecia buying propecia no prescription

generic propecia how cЙ‘n i get cheap propecia pills cost generic propecia online

cytotec online: buy cytotec online – order cytotec online

cost cheap propecia without dr prescription: buying generic propecia no prescription – buy generic propecia prices

http://finasteride.store/# get propecia tablets

how to get nolvadex nolvadex d tamoxifen chemo

http://lisinopril.network/# how to order lisinopril online

prinzide zestoretic: cheap lisinopril – buy lisinopril without prescription

get propecia no prescription: cost generic propecia for sale – cost of cheap propecia without dr prescription

tamoxifen lawsuit does tamoxifen make you tired effexor and tamoxifen

buy generic ciprofloxacin buy ciprofloxacin cipro online no prescription in the usa

buy cenforce: buy cenforce – Cenforce 150 mg online

buy cialis pill: Cialis 20mg price in USA – cialis for sale

п»їcialis generic buy cialis overseas Cialis 20mg price in USA

Vardenafil price Buy Vardenafil 20mg Levitra generic best price

https://cialist.pro/# buy cialis pill

http://viagras.online/# over the counter sildenafil

Levitra 10 mg best price: Levitra 20mg price – Vardenafil online prescription

Buy Cenforce 100mg Online: cheapest cenforce – order cenforce

Cialis without a doctor prescription Cialis 20mg price in USA cheapest cialis

http://cenforce.pro/# order cenforce

http://cenforce.pro/# Cenforce 100mg tablets for sale

Cialis 20mg price: Generic Tadalafil 20mg price – Cialis over the counter

super kamagra: buy kamagra online usa – cheap kamagra

Generic Cialis price buy cialis online Generic Tadalafil 20mg price

Cialis without a doctor prescription Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription п»їcialis generic

https://levitrav.store/# Levitra 10 mg best price

order viagra: Cheap Viagra 100mg – sildenafil online

https://cialist.pro/# Cheap Cialis

buy Levitra over the counter: Vardenafil online prescription – Levitra 20 mg for sale

Kamagra 100mg price kamagra buy kamagra online usa

cialis for sale Generic Cialis price Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription

https://cenforce.pro/# Cenforce 100mg tablets for sale

http://viagras.online/# Generic Viagra online

Sildenafil Citrate Tablets 100mg: Buy generic 100mg Viagra online – best price for viagra 100mg

buy cialis pill Generic Tadalafil 20mg price Cialis without a doctor prescription

Buy Vardenafil 20mg online: Levitra generic price – Levitra online USA fast

Cenforce 150 mg online Cenforce 150 mg online buy cenforce

https://kamagra.win/# Kamagra 100mg price

http://levitrav.store/# Cheap Levitra online

cenforce for sale: buy cenforce – Cenforce 150 mg online

best price for viagra 100mg Buy Viagra online cheap Viagra online price

Levitra 20 mg for sale: Buy Vardenafil 20mg – Levitra 10 mg buy online

canadian online pharmacy canadian pharmacy king canadian king pharmacy

canadian online drugstore: canadian pharmacy world reviews – legal canadian pharmacy online

reddit canadian pharmacy: canada pharmacy online legit – canada pharmacy 24h

indian pharmacy online online shopping pharmacy india world pharmacy india

legit non prescription pharmacies cheapest pharmacy mail order pharmacy no prescription

https://pharmnoprescription.icu/# discount prescription drugs canada

https://pharmindia.online/# india pharmacy

pharmacy discount coupons: online pharmacy – cheapest pharmacy to get prescriptions filled

canadian pharmacy: canada cloud pharmacy – online canadian pharmacy review

northern pharmacy canada best canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy world reviews

pharmacies in canada that ship to the us canadian pharmacies canadian mail order pharmacy

http://pharmcanada.shop/# canada rx pharmacy

https://pharmnoprescription.icu/# medications online without prescriptions

reputable mexican pharmacies online: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

canadian pharmacy world coupon: online pharmacy – canadian pharmacy world coupon

reputable canadian pharmacy precription drugs from canada canadian king pharmacy

best india pharmacy world pharmacy india п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

http://pharmmexico.online/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

https://pharmcanada.shop/# reliable canadian pharmacy

buy medicines online in india: top 10 online pharmacy in india – Online medicine order

how to order prescription drugs from canada: canada prescription online – buy medications online without prescription

mexican pharmacies no prescription prescription meds from canada canada mail order prescription

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

https://pharmmexico.online/# mexican pharmacy

https://pharmindia.online/# online pharmacy india

buy medication online without prescription: no prescription needed pharmacy – canadian prescription

canada online pharmacy: canada pharmacy reviews – online canadian pharmacy

canadian mail order pharmacy legit canadian pharmacy safe canadian pharmacy

canadian rx prescription drugstore how to order prescription drugs from canada mexican prescription drugs online

http://pharmmexico.online/# mexico pharmacy

https://pharmindia.online/# indian pharmacies safe

india pharmacy: world pharmacy india – indian pharmacy

no prescription medicine: non prescription online pharmacy – online drugs without prescription

indian pharmacy online Online medicine home delivery top 10 online pharmacy in india

canadapharmacyonline com cheap canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy sarasota

http://gabapentinneurontin.pro/# medicine neurontin

buy prednisone from canada: mail order prednisone – prednisone 10 mg tablet

http://doxycyclinea.online/# doxycycline without a prescription

3000mg prednisone: buy prednisone online fast shipping – prednisone brand name

neurontin tablets no script neurontin tablets uk neurontin price south africa

doxycycline medication doxycycline generic buy doxycycline online

doxycycline 500mg: doxycycline 100mg online – buy doxycycline online

https://gabapentinneurontin.pro/# purchase neurontin

buy azithromycin zithromax: where can i purchase zithromax online – zithromax for sale online

http://amoxila.pro/# amoxicillin 500mg

buy doxycycline online 270 tabs doxycycline how to order doxycycline

neurontin over the counter: gabapentin online – neurontin tablets no script

neurontin 4 mg: can i buy neurontin over the counter – neurontin 800mg

cost of amoxicillin 875 mg amoxicillin 500mg over the counter amoxicillin script

zithromax online paypal: how to get zithromax – where can you buy zithromax

how to buy amoxycillin: amoxacillian without a percription – generic amoxil 500 mg

https://doxycyclinea.online/# doxycycline 50 mg

http://doxycyclinea.online/# purchase doxycycline online

doxycycline 100mg tablets how to buy doxycycline online doxycycline 50mg

zithromax coupon buy azithromycin zithromax zithromax for sale cheap

zithromax for sale us: can you buy zithromax over the counter – average cost of generic zithromax

amoxicillin online canada: cost of amoxicillin 875 mg – amoxil pharmacy

http://amoxila.pro/# amoxicillin cost australia

http://amoxila.pro/# amoxicillin no prescription

gabapentin 600 mg where to buy neurontin neurontin 600 mg coupon

buy amoxicillin without prescription amoxicillin 500mg capsules antibiotic generic amoxicillin 500mg

antibiotic amoxicillin: amoxicillin 500mg capsules antibiotic – antibiotic amoxicillin

how to order doxycycline: doxy – doxycycline 100 mg

https://zithromaxa.store/# where can i buy zithromax uk

neurontin online usa neurontin 300 mg tablets medicine neurontin capsules

https://prednisoned.online/# 100 mg prednisone daily

generic doxycycline where to get doxycycline price of doxycycline