Author: Julián Monge Nájera, Ecologist and Photographer

In the Middle Ages, vassals cut down the vast forests than once ruled Europe, and built stone castles, meant to be inhabited by ladies and defended by knights in armor; these people would inspire the legends and fairy tales that still entertain our childhood. If there was no hill, the castle was built on the plains, but it was surrounded by moats and drawbridges. Centuries passed and cannons rendered the stone walls useless, so most of the castles were abandoned and slowly they have been falling apart, filling the soil with calcium carbonate and cracked stones, the ideal habitat for many land snails. When biologists looked closely at the species in these ruins, the surprise was not only what they found, but also what they did not find.

Ruins of a castle near Cork, Ireland. Source: Wikicommons

In a spectacular work in which over a decade she methodically collected snails from 123 European castles, Czech malacologist Lucia Jurickova found something unexpected and perhaps encouraging: eight species, some of them endangered, are much more common in castles. than in nature¹.

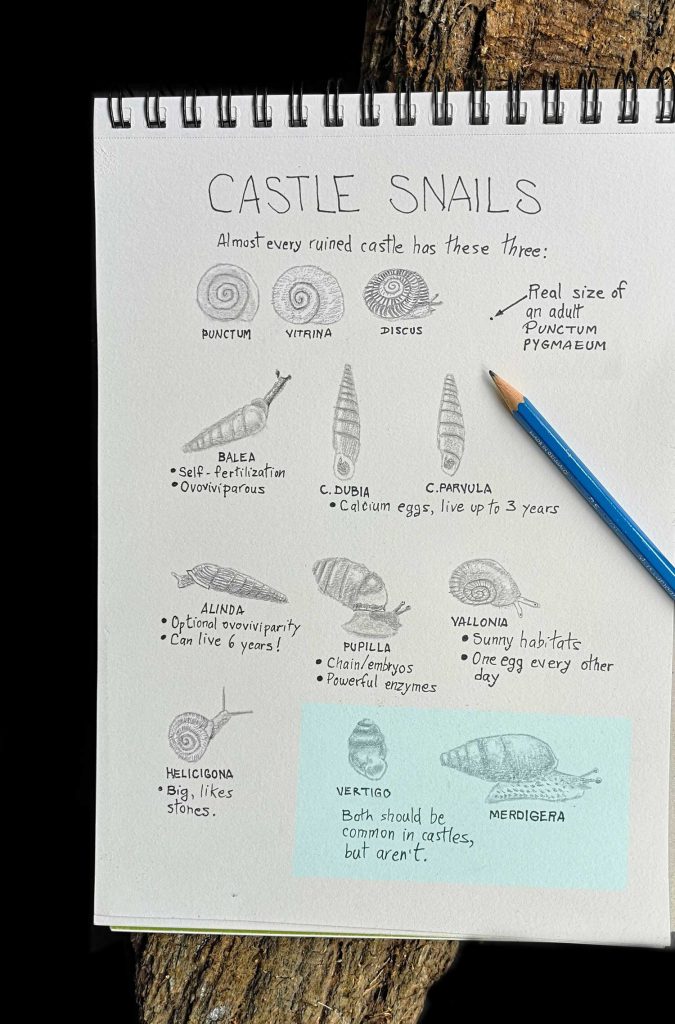

If there were tours to see snails in ruined castles, tourists could almost be guaranteed to see three species regardless of the castle: Punctum pygmaeum, Vitrina pellucida, and Discus rotundatus.

Punctum pygmaeum is, as its name suggests, tiny, measuring at most 1.5 mm in diameter when fully grown; it is found in much of Eurasia, in mosses, lichens, fallen vegetation, and stones, even if there is little calcium. It is hermaphroditic but has cross-mating, and it lays from 1 to 16 proportionally huge eggs.

The semi-slug Vitrina pellucida lives in forests as well as in meadows and gardens, where it eats decomposed vegetation, but it also scrapes liverworts, carrion, and feces. Their eggs are soft and their enemies include hedgehogs and the parasitic nematode Elaphostrongylus. It is a semi-slug because it is in the process of reducing its shell, in fact, it no longer fits in it.

The snail Discus rotundatus lives in fallen logs, litter, and even gardens, sometimes in groups, and is unaffected by low calcium soils; it lays 20 to 50 eggs in the litter and is moderately long-lived (3 years).

There is a second group, species that are more abundant in castles than in nature, and the first species in this group is Balea perversa, relatively well studied, although extinct in some parts of Europe. It lives in rocky substrates; especially if they have rough textures and are heated by the sun; where it feeds on bacteria, algae, and fungi. Like many other land snails, it produces eggs that need a couple of weeks to hatch, and the snails become adults within a few months. It is an unusual species because it tends to self-fertilize and keep the eggs inside the body until the babies are born.

The second species is Clausilia dubia, remarkable for having eggs with a calcified shell (a luxury among mollusks) and because despite its small size its lifespan exceeds 3 years. It is found in moist microhabitats on the ground, trees, and rock faces. Another species that practically has the same natural history is Clausilia parvula, but experts do not yet agree on whether it is a valid species or is the same Clausilia dubia.

The species Alinda biplicata is relatively large (2 cm long), long-lived (6 years) and produces up to 50 babies per year; it can lay eggs or retain them in the body until they hatch.

Next on the list is Pupilla muscorum, which is found in dunes, stones, and leaf litter; its reproductive tract is like a production line with a row of embryos in sequential stages of development, something spectacular and atypical among mollusks. It is also extraordinary for having the digestive enzymes needed to digest live vegetation (many snails can only digest decomposing vegetation).

In my sketchbook: three snails that are in practically every castles (top row); six species that are more abundant in castles than in nature, and, below in blue, the two species that should be common in castles but, for unknown reasons, are not. All this shows how much we still have to do in this area of malacology.

The tiny Vallonia costata is almost invisible and inhabits grasslands, rocky areas, and dunes. It lives for several years and every 1-4 days it lays an egg, which gives it enormous power of reproduction, which, together with its ability to live in sunny and dry places, explains why it is found throughout the Mediterranean basin.

Finally, a snail with a nice Latin name that means «stone killer», Helicigona lapicida, scrapes cyanobacteria and lichens from stones, even from gravestones in cemeteries. It is large (2 cm in diameter) and in an experiment in which specimens were marked, it was found that in one year the majority did not move more than 10 meters from the original location.

What do these species, so successful in castles, have in common?

That question has yet to be answered. Furthermore, there are two species that seem ideal to abound in castles but are not: Vertigo pygmaea and Merdigera obscura¹.

As its name suggests, Vertigo pygmaea is small and is found in moist and dry habitats. It is relatively abundant and, given its ecological needs, one might expect it to be common in castles, but it is only found in one out of ten castles, and as a rule, in small numbers. The other, Merdigera obscura, is seen with some frequency on logs, stones, and litter, even on walls, but it is also rare in castles. Why?

Even with her in-depth knowledge of European snails, Dr. Jurickova has yet to find the answer¹.

*Edited by Zaidett Barrientos, Katherine Bonilla y Carolina Seas.

Originally published in Blog Biología Tropical: 25 august 2020

REFERENCES

¹ Juřičková, L. (2005). Molluscs (Mollusca) of castles as an ecological phenomenon (Czech Republic). Historie, 102, 103; 100-148.