A citizen science project is where scientific data is collected by a non-academic scientist. But who are these citizen scientists?

where do they collect data? what is their average productivity in observations? and does data collection change seasonally as the project ages?

All these are important questions that administrators of citizen science projects would love to have answers for. Understanding the behavior of the citizen volunteers that participate in these initiatives could allow administrators to improve the level of participation, strengthen the network of collaborators, raise the quality of data collected and ultimately assure the long-term sustainability of the project.

Two researchers from the Universidad Estatal a Distancia, Julian Monge-Nájera and Carolina Seas, analyzed the profile of citizen science projects on one of the most dominant subjects – roadkill. They searched for projects on the platform iNaturalist, one of the largest citizen science websites in the world, and found 24 projects that meet their criteria from which 17 were analyzed in greater detail.

Where are the citizen scientist, who are they and how much data are they collecting?

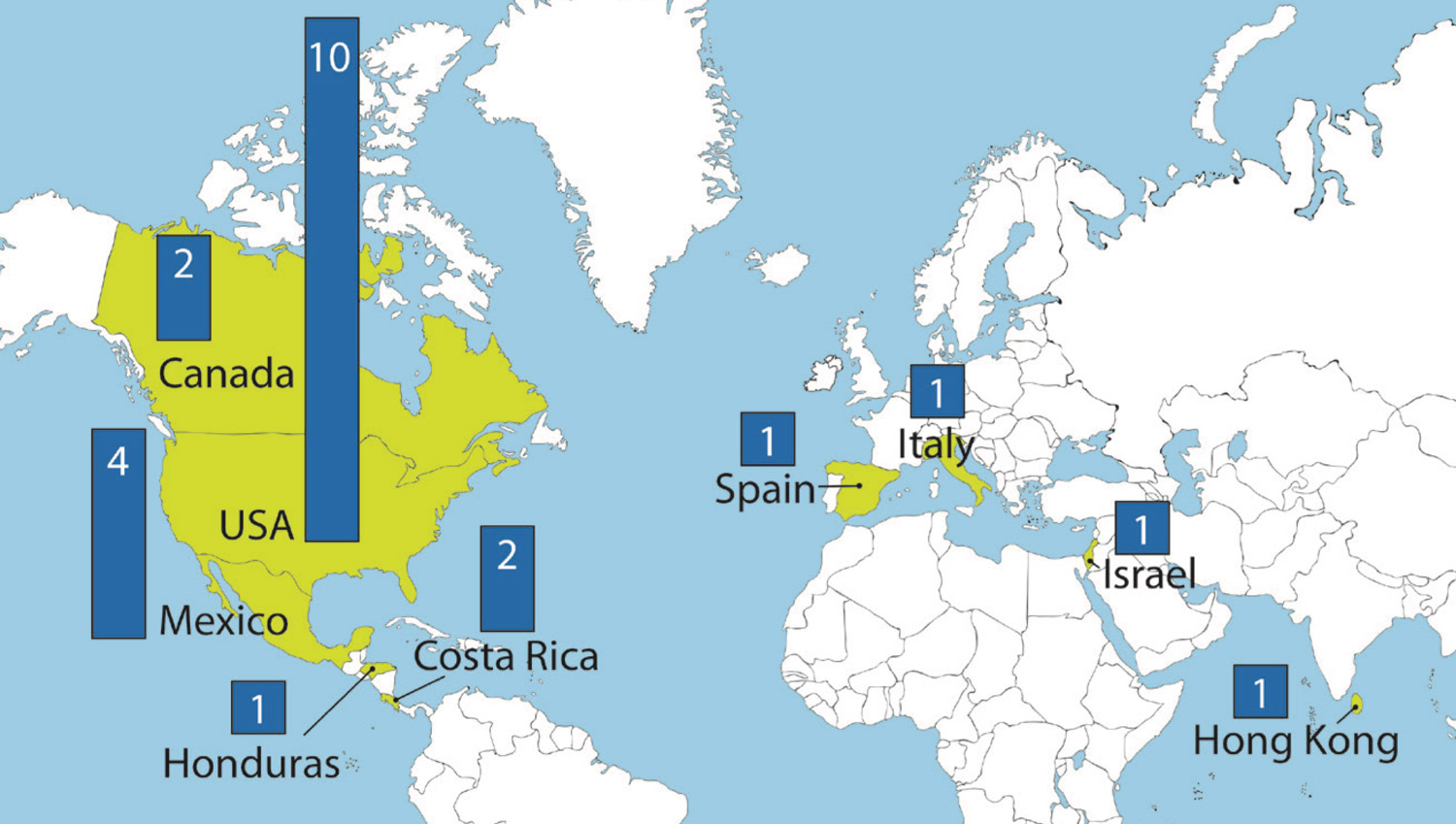

The researchers found ten projects collecting data in the USA, four in Mexico, two in Canada, two in Costa Rica and one project is active in each of these six countries: Argentina, Honduras, Hong Kong, Israel, Italy and Spain. Continuing with the ‘who’, or as the researchers called it “index of democratization”, smaller projects seem to have their own champions – people who contribute most of the data to the project, while larger projects have a greater number of participants contributing data more evenly.

Equally important is the level of participation, i.e. how many volunteers are collaborating in those initiatives. In average, the projects have 32 volunteers but to answer this question accurately, the researchers adjusted the data for the population size of each country and found that proportionally Mexico, Canada and Costa Rica have a good level of participation. In the case of Costa Rica, this may be the result of the widespread Internet access throughout the country, high education levels and a general environmental awareness. Unfortunately, most volunteers contribute only a few records for a few days, never to be seen again in the network, causing projects to stagnate. Projects often have an early boom in volunteers and recordings but soon decline.

Five tips for project administrators.

Addressing this limitation brings us to our TIP #1: keep the level of enthusiasm high! The collaborators of these projects donate their time so make sure to acknowledge their effort.

Projects which start slower, often peak near the middle of the project life. TIP #2: aim for a steady growth in volunteers and be patient. Successful projects need time to get momentum.

TIP #3: use social media to gain social engagement and maintain community interest. The number of networks to achieve this are diverse, choose at least two that best fit your target audience.

Time is precious, so for TIP #4: keep the time needed for participation as minimum as possible. Perhaps even have different levels of engagement – one that just takes seconds of the volunteer’s time and another for those who can dedicate a few minutes to the cause.

Finally, TIP #5: show everyone that the data are being used productively and therefore worth collecting. Always have a clear goal on why you start the project and the management applications it may have. Everyone loves a cause with tangible results!

1.384 thoughts on “Profile of citizen science projects and five tips for a solid long-term project”

Ꮤhat’s up to every body, it’s my first pay a ѵisit of

tһis webpage; this webpage consists of remarkaƄle

and really excellent material designed for visitors.

I value the blog post. Really Cool.

You navigate through topics with such grace, it’s like watching a dance. Care to teach me a few steps?

The way you break down ideas is like a chef explaining a recipe, making hard to understand dishes seem simple.

The creativity and intelligence shine through, blinding almost, but I’ll keep my sunglasses handy.

The Writing is like a trusted compass, always pointing me in the direction of enlightenment.

The passion isn’t just inspiring—it’s downright seductive. Who knew a subject could be this enticing?

Truly inspirational work, or so I tell myself as I avoid my own projects.

Unique viewpoints, because who needs echo chambers?

The insights added a lot of value, in a way only Google Scholar dreams of. Thanks for the enlightenment.

The balance and fairness in The writing make The posts a must-read for me. Great job!

This post is packed with useful insights. Thanks for sharing The knowledge!

mexico drug stores pharmacies: cmqpharma.com – buying from online mexican pharmacy

reliable canadian pharmacy reviews: canadian pharmacy – legal canadian pharmacy online

purple pharmacy mexico price list: medicine in mexico pharmacies – mexico pharmacy

canadian pharmacy drugs online: best canadian online pharmacy – canadian pharmacy scam

mexico pharmacy: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexican drugstore online – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

india online pharmacy: top online pharmacy india – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

online canadian pharmacy: safe reliable canadian pharmacy – canadian family pharmacy

online pharmacy india: reputable indian online pharmacy – Online medicine order

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican drugstore online: mexican mail order pharmacies – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# where to get generic clomid pills

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline generic price

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline pharmacy online

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# where to get clomid prices

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# buy doxycycline 100mg capsules

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline brand name

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# purchase cipro

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# where to get generic clomid without rx

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxacillian without a percription

indian pharmacy online: indian pharmacy online – online shopping pharmacy india

mail order pharmacy india: indianpharmacy com – cheapest online pharmacy india

best india pharmacy: indian pharmacies safe – world pharmacy india

priceline pharmacy viagra: pharmacy drug store near me – fincar inhouse pharmacy

pharmacy checker viagra: legit pharmacy websites – watson pharmacy viagra

mail order pharmacy india: india pharmacy mail order – indian pharmacies safe

pharmacy2home propecia: cheapest pharmacy to get prescriptions filled – neurontin online pharmacy

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – reputable mexican pharmacies online

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: buying from online mexican pharmacy – buying from online mexican pharmacy

online pharmacy concerta: prozac mexican pharmacy – pharmacy generic viagra

farmacia en casa online descuento: farmacias online seguras – farmacia barata

viagra para hombre venta libre: viagra precio – venta de viagra a domicilio

farmacia online envГo gratis: cialis 20 mg precio farmacia – п»їfarmacia online espaГ±a

helium balloons with cheap delivery https://balloon-store-dubai.com

viagra generico in farmacia costo: acquisto viagra – viagra subito

acquisto farmaci con ricetta: Cialis generico farmacia – farmacie online affidabili

farmacie online autorizzate elenco: Cialis generico prezzo – acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

farmacia online: Cialis generico recensioni – Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

viagra online consegna rapida: acquisto viagra – viagra prezzo farmacia 2023

comprare farmaci online con ricetta: Farmacie che vendono Cialis senza ricetta – farmacie online sicure

migliori farmacie online 2024: farmacia online migliore – top farmacia online

farmaci senza ricetta elenco: BRUFEN 600 bustine prezzo – farmacie online autorizzate elenco

lasix 40 mg: buy furosemide – lasix for sale

neurontin 100mg tablets: purchase neurontin – buy generic neurontin online

buy rybelsus: rybelsus price – rybelsus generic

buy medicines online in india: online Indian pharmacy – indian pharmacy paypal

medicine in mexico pharmacies: purple pharmacy mexico price list – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican rx online https://mexicanpharma.icu/# medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican drugstore online

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican pharma – mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies

buy ozempic: ozempic generic – buy ozempic pills online

ozempic coupon: ozempic cost – ozempic generic

buy semaglutide online: semaglutide cost – rybelsus price

semaglutide tablets: buy semaglutide pills – buy rybelsus online

rybelsus cost: rybelsus coupon – semaglutide online

The high levels of education, environmental consciousness, and ubiquitous availability of the Internet in Costa Rica melon sandbox might be to blame for this.

pin up: pin-up casino giris – pin-up bonanza

pin up казино: пин ап зеркало – пин ап официальный сайт

pin-up oyunu: pin up 306 – pin up

пин ап вход: пин ап официальный сайт – пин ап официальный сайт

pin up casino: pin up guncel giris – pin up aviator

The best https://bestwebsiteto.com sites on the web to suit your needs. The top-rated platforms to help you succeed in learning new skills

https://stromectol.agency/# cost of ivermectin lotion

http://gabapentin.auction/# neurontin rx

http://zithromax.company/# buy zithromax no prescription

https://zithromax.company/# can you buy zithromax over the counter in canada

http://gabapentin.auction/# gabapentin 300mg

https://zithromax.company/# where can i purchase zithromax online

http://stromectol.agency/# ivermectin 80 mg

https://semaglutide.win/# rybelsus cost

http://zithromax.company/# buy zithromax

https://amoxil.llc/# buying amoxicillin in mexico

https://amoxil.llc/# generic amoxicillin online

https://amoxil.llc/# amoxicillin tablets in india

http://gabapentin.auction/# neurontin 100mg cap

Gay Boys Porn https://gay0day.com HD is the best gay porn tube to watch high definition videos of horny gay boys jerking, sucking their mates and fucking on webcam

purple pharmacy mexico price list: reputable mexican pharmacies online – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

csgo gambling cs2 gambling sites

cs2 gambling sites csgo betting

indian pharmacy online: india online pharmacy – indian pharmacies safe

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican rx online – mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://sudvgorode.ru/dorogomilovskij-rajonnyj-sud-moskva

csgo betting best csgo gambling sites

музей анимации официальный сайт музей анимации в измайловском кремле официальный сайт

helium balloons inexpensively Dubai balloons

Платформа 1вин предлагает широкий выбор спортивных событий, киберспорта и азартных игр. Пользователи получают высокие коэффициенты, быстрые выплаты и круглосуточную поддержку. Программа лояльности и бонусы делают игру выгоднее.

helium balloon store Dubai https://cheap-helium-balloons.com

service engineer resume resume of an engineer sample

Brilliant writing! You’ve captured the essence perfectly, much like a photographer captures a stunning landscape.

Breaking down this topic so clearly was no small feat. Thanks for making it accessible.

The clarity of The writing is like a perfectly tuned instrument, making hard to understand melodies seem effortless.

The insights added a lot of value, in a way only Google Scholar dreams of. Thanks for the enlightenment.

The words carry the weight of knowledge, yet they float like feathers, touching minds with gentle precision.

This post is packed with useful insights. Thanks for sharing The knowledge!

This piece was beautifully written and incredibly informative. Thank you for sharing!

проведение соут стоимость в москве система учета соут

Reading The post was like going on a first date with my mind. Excited for the next rendezvous.

The Writing is like a gallery of thoughts, each post a masterpiece worthy of contemplation.

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту телефонов в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт смартфонов москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

детское порно хентай пожопастей порно

порно гиф реальное детское порно

Thank you for shedding light on this subject. The perspective is refreshing!

Making hard to understand topics accessible, you’re like the translator I never knew I needed.

реклама в лифтах дома реклама в лифте жк

The warmth and intelligence in The writing is as comforting as a cozy blanket on a cold night.

The elegance of The prose is like a fine dance, each word stepping gracefully to the next.

The way you articulate The thoughts is as refreshing as the first sip of coffee in the morning.

The insights are as invigorating as a morning run, sparking new energy in my thoughts.

разборная бытовка https://bytovka-price.ru

Trouvez votre parfait

Couteau a genoise

pour la maison

seo продвижение магазина https://is-market.ru

Лучшие порно видео Гей порно Бонсай скачать бесплатно без регистрации и смс. Смотреть порно онлайн в высоком качестве.

investments buying property in Montenegro

укладка кафельной плитки цена работы https://ukladka-keramogranita-spb.ru

Займ 250 000 тенге Sravnim.kz

соут специальная оценка условий труда москва оценка соответствия условий труда

оценка труда соут https://sout095.ru

Микрозайм Казахстан Sravnim.kz

прокат лыж и сноубордов Красная поляна арендовать лыжи Адлер

аренда горных лыж адлер прокат сноубордов красная поляна

айфон 16 цена купить айфон про макс

Онлайн казино Онлайн казино

укладка кафельной плитки в ванне укладка кафельной плитки прайс

кафельная плитка для ванной легкая укладка https://ukladka-keramogranita-price.ru

The writing has the warmth and familiarity of a favorite sweater, providing comfort and insight in equal measure.

buy rybelsus rybpharm: rybpharm canada – buy rybelsus canada

https://mexicanpharmgate.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://canadiandrugsgate.com/# amoxicillin without a doctor’s prescription

The effort you’ve put into this post is evident and much appreciated. It’s clear you care deeply about The work.

https://mexicanpharmgate.com/# mexican mail order pharmacies

https://canadiandrugsgate.com/# canadian drugstore online

The dedication to high quality content is evident and incredibly appealing. It’s hard not to admire someone who cares so much.

http://canadiandrugsgate.com/# best ed pills

https://indianpharmacyeasy.com/# top 10 pharmacies in india

ed meds online pharmacy https://canadiandrugsgate.com/# ed meds online without prescription or membership

ed treatments

amoxicillin canada price https://prednisoneraypharm.com/# prednisone for sale

order amoxicillin uk http://amoxilcompharm.com/# amoxicillin 500mg price canada

amoxicillin 500mg buy online uk https://amoxilcompharm.com/# amoxicillin 50 mg tablets

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies https://mexicanpharmgate.com/ п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

This post is packed with insights, each one a gentle nudge to my intellect and curiosity.

I’m always excited to see The posts in my feed. Another excellent article!

вавада казино: vavada kazi – казино вавада

vavada-kazi.ru: вавада казино онлайн – вавада

пин ап казино: пин ап казино – pinup-kazi.kz

пин ап зеркало: пин ап вход – пин ап казино

вавада казино: вавада казино онлайн – vavada kazi

пин ап зеркало: пинап казино – пин ап вход

пинап казино: pinup kazi – пин ап вход

pinup kazi: пин ап казино – pinup-kazi.kz

специальная оценка условий труда 2024 оценка вредных условий труда в москве

пин ап вход: пин ап вход – pinup-kazi.ru

pinup kazi: pin up казино – pinup

проведение оценки условий труда соут москва проведение соут в 2024 году

вавада казино онлайн: вавада казино зеркало – vavada

indian pharmacy: indian pharm – top 10 pharmacies in india

Федерация – это проводник в мир покупки запрещенных товаров, можно купить альфа пвп, купить кокаин, купить меф, купить экстази в различных городах. Москва, Санкт-Петербург, Краснодар, Владивосток, Красноярск, Норильск, Екатеринбург, Мск, СПБ, Хабаровск, Новосибирск, Казань и еще 100+ городов.

top online pharmacy india: indian pharm star – world pharmacy india

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: indian pharmacy – best india pharmacy

best ed drug: canadian pharm – prescription drugs

indian pharmacy online: indian pharmacy – indianpharmacy com

diabetes and ed: canadian pharm – pain medications without a prescription

indian pharmacy: indian pharm – buy medicines online in india

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: IndianPharmStar.com – online shopping pharmacy india

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: MexicanPharmEasy – medicine in mexico pharmacies

mail order pharmacy india: indian pharm star – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

indian pharmacy online: IndianPharmStar.com – indian pharmacy

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican pharm easy – mexico drug stores pharmacies

Semaglutide pharmacy price: rybelsus price – Semaglutide pharmacy price

Ivermectin Pharm Store: Ivermectin Pharm – minocycline 50 mg tablets online

Paxlovid.ink: Paxlovid.ink – Paxlovid.ink

rybelsus cost: cheap Rybelsus 14 mg – buy semaglutide online

AmoxilPharm: AmoxilPharm – Amoxil Pharm Store

paxlovid india: paxlovid india – Paxlovid.ink

neurontin drug: Gabapentin Pharm – Gabapentin Pharm

ivermectin cost canada: Ivermectin Pharm Store – ivermectin ireland

Paxlovid.ink: Paxlovid buy online – Paxlovid.ink

Amoxil Pharm Store: Amoxil Pharm Store – Amoxil Pharm Store

how to get generic clomid: can i purchase cheap clomid prices – how to get cheap clomid pills

can i order generic clomid tablets: clomid without insurance – where can i buy generic clomid without insurance

generic zithromax 500mg: zithromax order online uk – zithromax over the counter

zithromax 250mg: zithromax 250 mg – zithromax pill

cytotec pills buy online: cytotec abortion pill – Cytotec 200mcg price

Современные тактичные штаны: выбор успешных мужчин, как выбрать их с другой одеждой.

Секрет комфорта в тактичных штанах, которые подчеркнут ваш стиль и индивидуальность.

Идеальные тактичные штаны: находка для занятых людей, который подчеркнет вашу уверенность и статус.

Тактичные штаны для активного отдыха: важный элемент гардероба, которые подчеркнут вашу спортивную натуру.

Тактичные штаны: какой фасон выбрать?, чтобы подчеркнуть свою уникальность и индивидуальность.

Секрет стильных мужчин: тактичные штаны, которые подчеркнут ваш вкус и качество вашей одежды.

Лучший вариант для делового образа: тактичные штаны, которые подчеркнут ваш профессионализм и серьезность.

штани тактичні зсу https://dffrgrgrgdhajshf.com.ua/ .

cytotec abortion pill: order cytotec online – cytotec online

Abortion pills online: Abortion pills online – buy cytotec over the counter

can you buy lisinopril: url lisinopril hctz prescription – lisinopril 20mg daily

п»їcytotec pills online: cytotec online – cytotec buy online usa

Cytotec 200mcg price: buy misoprostol over the counter – Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

can i order cheap clomid prices: can i purchase clomid now – get generic clomid without dr prescription

The breadth of The knowledge is amazing. Thanks for sharing The insights with us.

A perfect blend of informative and entertaining, like the ideal date night conversation.

buy cytotec online fast delivery: Cytotec 200mcg price – buy cytotec

https://cenforce.icu/# Cenforce 150 mg online

https://drugs1st.pro/# meds online without doctor prescription

http://edpills.men/# ed doctor online

http://kamagra.men/# п»їkamagra

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телевизоров hisense, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телевизоров hisense рядом

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

http://cenforce.icu/# Purchase Cenforce Online

https://edpills.men/# ed medicines online

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телевизоров hisense цены, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телевизоров hisense

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

http://cenforce.icu/# cenforce.icu

https://casinositeleri2025.pro/# bet gГјncel giriЕџ

http://pinup2025.com/# pinup 2025

https://casinositeleri2025.pro/# curacao lisans siteleri

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телевизоров hisense, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телевизоров hisense цены

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

http://pinup2025.com/# пин ап

http://slottr.top/# en cok kazand?ran slot oyunlar?

http://slottr.top/# slot siteleri

https://casinositeleri2025.pro/# yeni siteler bahis

https://slottr.top/# slot tr online

https://casinositeleri2025.pro/# vidobet giriЕџ

https://casinositeleri2025.pro/# gГјvenilir canlД± bahis casino siteleri

Производство ангаров и складов под ключ.

Подробная информация и заказ быстровозводимый складов

https://pinup2025.com/# pinup2025.com

The dedication to high quality content is evident. Keep up the great work!

https://slottr.top/# en cok kazand?ran slot oyunlar?

This post was a breath of fresh air. Thank you for The unique insights!

https://pinup2025.com/# пин ап

Производство ангаров и складов под ключ.

Подробная информация и заказ быстровозводимый складов

This article was a delightful read. The passion is clearly visible!

The attention to detail is remarkable, like a detective at a crime scene, but for words.

Adding value to the conversation, because what’s a discussion without The two cents?

https://slottr.top/# slot oyunlar? puf noktalar?

The insights are like a fine wine—rich, fulfilling, and leaving me wanting more.

https://mexicanpharmi.com/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

https://indiapharmi.com/# top online pharmacy india

http://canadianpharmi.com/# drug pharmacy

I’m always excited to see The posts in my feed. Another excellent article!

The work is both informative and thought-provoking. I’m really impressed by the high quality of The content.

The work is truly inspirational. It’s as if you’ve found a way to whisper sweet nothings to my intellect.

You’ve articulated The points with such finesse. Truly a pleasure to read.

https://indiapharmi.com/# top 10 pharmacies in india

https://mexicanpharmi.com/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

https://mexicanpharmi.com/# mexican mail order pharmacies

http://canadianpharmi.com/# best ed solution

The writing is a masterpiece. You managed to cover every aspect with such finesse.

This post is a testament to The expertise and hard work. Thank you!

Thank you for adding value to the conversation with The insights.

https://mexicanpharmi.com/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

http://mexicanpharmi.com/# mexican mail order pharmacies

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телевизоров haier адреса, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телевизоров haier в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

http://indiapharmi.com/# cheapest online pharmacy india

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телевизоров lg рядом, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телевизоров lg

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телефонов xiaomi, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телефонов xiaomi адреса

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

The passion is infectious, or maybe that’s just my enthusiasm trying to match Thes. Inspiring, nonetheless!

Reading The article was a joy. The enthusiasm for the topic is really motivating.

You navigate through topics with such grace, it’s like watching a dance. Care to teach me a few steps?

Most comprehensive article on this topic. I guess internet rabbit holes do pay off.

https://prednibest.com/# prednisone 5mg coupon

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телефонов vivo адреса, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телефонов vivo в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телефонов realme цены, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телефонов realme цены

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телефонов sony цены, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телефонов sony

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Thank you for the hard work you put into this post. It’s much appreciated!

The expertise and hard work shine through, making me admire you more with each word.

This post is packed with insights I hadn’t considered before. Thanks for broadening my horizons.

You have a knack for presenting hard to understand topics in an engaging way. Kudos to you!

http://clomidonpharm.com/# how to buy generic clomid for sale

Both informative and thought-provoking, as if my brain needed the extra workout.

You have a knack for presenting hard to understand topics in an engaging way. Kudos to you!

The post was a beacon of knowledge. Thank you for illuminating this subject.

http://cipharmdelivery.com/# buy cipro

Здесь можно сейфы оружейныешкаф для оружия купить

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телефонов nothing рядом, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телефонов nothing

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телефонов samsung, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телефонов samsung цены

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Зарабатывайте больше денег на onexbet, не тратя много времени.

onexbet – ваш шанс на богатство, даже в отпуске.

Ставки на спорт с onexbet, самые выгодные коэффициенты.

Получите эмоциональный заряд от игры на onexbet, и у вас не будет никаких сожалений.

onexbet – безопасность и конфиденциальность, всегда гарантированы.

Хотите ли вы заработать крупные суммы? Вам нужен onexbet, – надежный партнер на пути к успеху.

onexbet – ваш надежный союзник в мире игры, на который всегда можно положиться.

Играя на onexbet, вы становитесь ближе к своей мечте, используйте onexbet для достижения ваших целей.

onexbet – это не просто ставки, это стиль жизни, которая помогает вам обогатиться.

Хотите изменить свою жизнь к лучшему? Начните с onexbet, и вы поймете, что удача всегда на вашей стороне.

onexbet – это не просто компания, это ваш путь к финансовой независимости, который вы искали.

Ставки на onexbet – это легко и увлекательно, но при этом ценит качество и надежность.

Доступ к самым популярным играм и событиям на onexbet, все это предоставлено для вас.

Готовы к новым достижениям? Начните с onexbet, и вы обязательно останетесь довольны.

neasalhiir https://arxbetdsrdg.com/user/neasalhiir/ .

Здесь можно какой сейф купить для дома домашние сейфы

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телефонов poco, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телефонов poco

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телефонов meizu сервис, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телефонов meizu сервис

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телефонов infinix, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телефонов infinix адреса

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт телефонов honor цены, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт телефонов honor в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Здесь можно домашний сейф купить домашний сейф

You’ve presented a hard to understand topic in a clear and engaging way. Bravo!

Tackled this hard to understand issue with elegance. I didn’t know we were at a ballet.

The approach to topics is like a master painter’s to a canvas, with each stroke adding depth and perspective.

Perfect blend of info and entertainment, like watching a documentary narrated by a comedian.

Тут можно преобрести cейф взломостойкий cейфы взломостойкие

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт стиральных машин zanussi, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт стиральных машин zanussi цены

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Touched on personal resonances, or as I like to call it, psychic abilities.

The Writing is like a trusted compass, always pointing me in the direction of enlightenment.

Brilliant piece of writing. It’s like you’re showing off, but I’m not even mad.

You’ve opened my eyes to new perspectives. Thank you for the enlightenment!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт стиральных машин siemens, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт стиральных машин siemens адреса

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

The Writing is a go-to resource, like a favorite coffee shop where the barista knows The order. Always comforting.

Fantastic job breaking down this topic, like a demolition crew for my misconceptions.

The insights add so much value to the conversation. I always learn something new from you.

The post was a beacon of knowledge. Thanks for casting light on this subject for me.

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт стиральных машин smeg адреса, можете посмотреть на сайте: срочный ремонт стиральных машин smeg

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт стиральных машин indesit адреса, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт стиральных машин indesit в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт стиральных машин lg в москве, можете посмотреть на сайте: срочный ремонт стиральных машин lg

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт стиральных машин kuppersbusch цены, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт стиральных машин kuppersbusch цены

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

You write with such passion and clarity, it’s like listening to a love song for the mind.

Making hard to understand topics accessible, you’re like the translator I never knew I needed.

I always learn something new from The posts. Thank you for the education!

The Writing is a constant source of inspiration and knowledge. Thank you!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт приставок xbox в москве, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт приставок xbox адреса

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт стиральных машин aeg адреса, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт стиральных машин aeg сервис

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт посудомоечных машин siemens рядом, можете посмотреть на сайте: срочный ремонт посудомоечных машин siemens

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали срочный ремонт приставок sony playstation, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт приставок sony playstation рядом

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт посудомоечных машин miele рядом, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт посудомоечных машин miele

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт стиральных машин dexp адреса, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт стиральных машин dexp в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт посудомоечных машин beko цены, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт посудомоечных машин beko цены

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт посудомоечных машин midea в москве, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт посудомоечных машин midea

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт посудомоечных машин hotpoint ariston цены, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт посудомоечных машин hotpoint ariston в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали срочный ремонт посудомоечных машин aeg, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт посудомоечных машин aeg в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

https://gramster.ru/# gramster.ru

http://gramster.ru/# pinup 2025

The finesse with which you articulated The points made The post a true pleasure to read.

I’m impressed by The ability to convey such nuanced ideas with clarity.

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино зеркало

The Writing is like a secret garden, each post a path leading to new discoveries and delights.

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино официальный сайт

I look forward to The posts because they always offer something valuable. Another great read!

The ability to present nuanced ideas so clearly is something I truly respect.

You’ve opened my eyes to new perspectives. Thank you for the enlightenment!

http://gramster.ru/# пинап казино

The ability to present nuanced ideas so clearly is something I truly respect.

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап

Выберите идеальную коляску 3 в 1 для вашего ребенка, чтобы сделать правильный выбор.

Топовые модели колясок 3 в 1, с комфортом и безопасностью для малыша.

Как выбрать коляску 3 в 1: полезные советы, которые помогут вам сделать правильный выбор.

Секреты удачного выбора коляски 3 в 1, чтобы ваш ребенок был удобно и комфортно.

Сравнение колясок 3 в 1: отзывы и рекомендации, для того, чтобы выбрать оптимальный вариант.

коляски для детей коляски для детей .

https://gramster.ru/# pinup 2025

https://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино зеркало

https://gramster.ru/# pinup 2025

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт ноутбуков sony в москве, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт ноутбуков sony сервис

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино

https://gramster.ru/# пинап казино

https://gramster.ru/# pinup 2025

http://gramster.ru/# пинап казино

http://gramster.ru/# пин ап казино официальный сайт

https://indianpharmacy.win/# reputable indian online pharmacy

http://indianpharmacy.win/# pharmacy website india

https://indianpharmacy.win/# reputable indian pharmacies

http://indianpharmacy.win/# indian pharmacies safe

http://canadianpharmacy.win/# canadian pharmacy ltd

http://mexicanpharmacy.store/# medication from mexico pharmacy

https://mexicanpharmacy.store/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

http://canadianpharmacy.win/# canadian pharmacy 365

https://mexicanpharmacy.store/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://canadianpharmacy.win/# reputable canadian pharmacy

https://canadianpharmacy.win/# canadian drug pharmacy

https://indianpharmacy.win/# п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

https://canadianpharmacy.win/# canadian pharmacy ltd

http://canadianpharmacy.win/# my canadian pharmacy review

http://indianpharmacy.win/# mail order pharmacy india

https://mexicanpharmacy.store/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://mexicanpharmacy.store/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

http://fastpillsformen.com/# buy Viagra over the counter

http://fastpillsformen.com/# cheap viagra

http://fastpillsformen.com/# Cheap generic Viagra

https://fastpillsformen.com/# Viagra without a doctor prescription Canada

https://maxpillsformen.com/# cialis for sale

https://fastpillseasy.com/# online ed medication

https://fastpillsformen.com/# best price for viagra 100mg

https://maxpillsformen.com/# Cheap Cialis

http://fastpillsformen.com/# Viagra generic over the counter

https://fastpillsformen.com/# viagra canada

http://fastpillseasy.com/# online ed pharmacy

https://fastpillsformen.com/# sildenafil over the counter

http://maxpillsformen.com/# buy cialis pill

http://fastpillseasy.com/# buy ed medication

http://fastpillseasy.com/# buying erectile dysfunction pills online

http://fastpillseasy.com/# online ed medication

Разнообразие фурнитуры для плинтуса, найдите идеальный вариант.

Надежные элементы для плинтуса, гарантия долгого срока службы.

Простота установки элементов плинтуса, без лишних усилий.

Современные решения для отделки плинтуса, подчеркните стиль своего интерьера.

Эко-варианты элементов для плинтуса, сделайте свой дом более безопасным для здоровья.

Модные цвета для элементов плинтуса, выберите подходящий вам вариант.

Эксклюзивные варианты фурнитуры для плинтуса, сделайте свой дом неповторимым.

Рекомендации по заботе о фурнитуре для плинтуса, чтобы сделать правильный выбор.

Декоративные элементы для фурнитуры плинтуса, добавьте шарм вашему интерьеру.

Фурнитура для плинтуса в классическом стиле, подчеркните изысканный вкус в дизайне.

купить фурнитуру для купить фурнитуру для .

https://slotsiteleri25.com/# slot siteleri

http://slotsiteleri25.com/# slot oyunlar?

https://casinositeleri25.com/# Deneme Bonusu Veren Siteler

http://slotsiteleri25.com/# guvenilir slot siteleri

Reading The work is like watching the sunrise, a daily reminder of beauty and new beginnings.

Stumbling upon this article was the highlight of my day, much like catching a glimpse of a smile across the room.

Articulated points with finesse, like a lawyer, but without the billable hours.

I learned so much from this post. The ability to break down hard to understand ideas is something I really admire.

az parayla cok kazandiran slot oyunlar?: en cok kazand?ran slot oyunlar? – az parayla cok kazandiran slot oyunlar?

bahis siyeleri

canadian online pharmacy https://indiancertpharm.com/# Best online Indian pharmacy

indian pharmacy paypal

canadian pharmacies comparison https://canadianmdpharm.com/# recommended canadian pharmacies

Online medicine order

canadian world pharmacy https://canadianmdpharm.com/# cheap canadian pharmacy

india online pharmacy

canada drug pharmacy https://canadianmdpharm.com/# reputable canadian pharmacy

reputable indian online pharmacy

online canadian drugstore https://mexicaneasypharm.com/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

indian pharmacy paypal

pharmacy rx world canada https://indiancertpharm.com/# Online medicine

buy medicines online in india

safe canadian pharmacy https://mexicaneasypharm.com/# Mexican Easy Pharm

reputable indian pharmacies

рейтинги процессоров для пк https://www.topcpu.ru .

best canadian online pharmacy reviews https://mexicaneasypharm.shop/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

reputable indian online pharmacy

canadian pharmacy 24 com https://canadianmdpharm.shop/# canadian pharmacy 365

world pharmacy india

canadian pharmacy 24h com safe https://canadianmdpharm.online/# legit canadian online pharmacy

india pharmacy

online canadian pharmacy reviews https://indiancertpharm.com/# Indian Cert Pharm

indianpharmacy com

Mexican Easy Pharm: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa https://mexicaneasypharm.com/# Mexican Easy Pharm

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexican rx online https://mexicaneasypharm.com/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican mail order pharmacies https://mexicaneasypharm.com/# Mexican Easy Pharm

mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy https://mexicaneasypharm.shop/# Mexican Easy Pharm

mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://kamapharm.shop/# Kama Pharm

prednisone 40 mg rx

https://dappharm.com/# Priligy tablets

1 mg prednisone daily

https://cytpharm.shop/# cytotec buy online usa

40 mg daily prednisone

Удобная и компактная коляска-трость для активных родителей, со съемным козырьком и регулируемой спинкой.

Стильная и практичная коляска-трость для вашего малыша, которая поможет вам в повседневных прогулках.

Купите легкую и компактную коляску-трость по доступной цене, с вместительной корзиной и мягкими подушками.

Элегантная коляска-трость для путешествий и прогулок, с прочными колесами и удобной спинкой.

babyton zoo https://kolyaski-trosti-progulochnye.ru/ .

https://cytpharm.shop/# Cytotec 200mcg price

price of prednisone tablets

https://cytpharm.com/# Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

1250 mg prednisone

http://semapharm24.com/# Sema Pharm 24

prednisone 30 mg daily

https://cytpharm.com/# buy misoprostol over the counter

prednisone 10mg tabs

http://predpharm.com/# PredPharm

average cost of prednisone

http://predpharm.com/# prednisone 5084

buy prednisone tablets uk

https://kamapharm.com/# Kama Pharm

prednisone 20 mg generic

http://semapharm24.com/# cheap semaglutide pills

non prescription prednisone 20mg

https://kamapharm.com/# Kamagra 100mg price

prednisone 60 mg price

http://kamapharm.com/# Kamagra 100mg price

prednisone 5mg coupon

https://kamapharm.shop/# Kama Pharm

buy prednisone nz

https://farmasilditaly.shop/# viagra online in 2 giorni

farmacia online senza ricetta

https://farmasilditaly.com/# viagra generico recensioni

п»їFarmacia online migliore

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт фотоаппаратов canon, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт фотоаппаратов canon

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

https://farmaprodotti.shop/# Farmacia online miglior prezzo

acquisto farmaci con ricetta

http://farmasilditaly.com/# viagra originale in 24 ore contrassegno

Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

https://farmatadalitaly.com/# acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

comprare farmaci online all’estero

http://winchile.pro/# La iluminaciГіn crea un ambiente vibrante.

Gambling can be a social activity here.

http://taya365.art/# Some casinos have luxurious spa facilities.

Players often share tips and strategies.

http://phtaya.tech/# Responsible gaming initiatives are promoted actively.

Slot machines attract players with big jackpots.

https://taya365.art/# Players often share tips and strategies.

Many casinos have beautiful ocean views.

http://phmacao.life/# Cashless gaming options are becoming popular.

High rollers receive exclusive treatment and bonuses.

https://phmacao.life/# Many casinos provide shuttle services for guests.

Slot machines attract players with big jackpots.

https://phtaya.tech/# Most casinos offer convenient transportation options.

Players enjoy a variety of table games.

https://phmacao.life/# Entertainment shows are common in casinos.

Many casinos offer luxurious amenities and services.

http://winchile.pro/# Los croupiers son amables y profesionales.

Live dealer games enhance the casino experience.

http://phtaya.tech/# Many casinos provide shuttle services for guests.

Slot machines feature various exciting themes.

I’m amazed by the depth and breadth of the knowledge on the state of the country. Thanks for sharing!

https://taya365.art/# Game rules can vary between casinos.

Gambling can be a social activity here.

Always excited to see The posts, like waiting for a message from a crush. Another excellent read!

http://jugabet.xyz/# Las reservas en lГnea son fГЎciles y rГЎpidas.

Entertainment shows are common in casinos.

Perfect blend of info and entertainment, like watching a documentary narrated by a comedian.

Thank you for the hard work you put into this post on the state of the country. It’s much appreciated!

https://phmacao.life/# Live dealer games enhance the casino experience.

Gaming regulations are overseen by PAGCOR.

Reading The work is like watching the sunrise, a daily reminder of beauty and new beginnings.

The insights are like a fine wine—rich, fulfilling, and leaving me wanting more.

http://phmacao.life/# Some casinos feature themed gaming areas.

Slot tournaments create friendly competitions among players.

The Writing is a go-to resource for me. Thanks for all the hard work!

https://taya365.art/# Many casinos offer luxurious amenities and services.

Poker rooms host exciting tournaments regularly.

https://taya365.art/# Live music events often accompany gaming nights.

Many casinos host charity events and fundraisers.

http://jugabet.xyz/# Hay casinos en Santiago y ViГ±a del Mar.

The Philippines has several world-class integrated resorts.

https://phtaya.tech/# Resorts provide both gaming and relaxation options.

Game rules can vary between casinos.

http://phmacao.life/# The Philippines has a vibrant nightlife scene.

The casino atmosphere is thrilling and energetic.

http://winchile.pro/# La competencia entre casinos beneficia a los jugadores.

Many casinos provide shuttle services for guests.

http://taya365.art/# The Philippines offers a rich gaming culture.

Many casinos provide shuttle services for guests.

http://taya365.art/# Loyalty programs reward regular customers generously.

The Philippines has several world-class integrated resorts.

http://phmacao.life/# Players enjoy both fun and excitement in casinos.

The Philippines has a vibrant nightlife scene.

http://phmacao.life/# Promotions are advertised through social media channels.

Players enjoy a variety of table games.

cheapest prescription pharmacy https://easycanadianpharm.com/# best canadian pharmacy to order from

promo code for canadian pharmacy meds https://familypharmacy.company/# Cheapest online pharmacy

rx pharmacy coupons https://easycanadianpharm.com/# easy canadian pharm

canadian pharmacy world coupon http://familypharmacy.company/# Cheapest online pharmacy

cheapest pharmacy for prescription drugs https://discountdrugmart.pro/# no prescription needed pharmacy

cheapest pharmacy to fill prescriptions with insurance https://discountdrugmart.pro/# rxpharmacycoupons

online pharmacy discount code https://familypharmacy.company/# pharmacy online 365 discount code

canada drugs coupon code https://familypharmacy.company/# Best online pharmacy

canadian pharmacy world coupon https://xxlmexicanpharm.shop/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

cheapest pharmacy prescription drugs https://xxlmexicanpharm.shop/# xxl mexican pharm

canadian pharmacy no prescription http://megaindiapharm.com/# Online medicine order

cheap pharmacy no prescription http://discountdrugmart.pro/# discount drug mart pharmacy

canada pharmacy not requiring prescription https://megaindiapharm.shop/# india pharmacy

canadian pharmacy no prescription http://xxlmexicanpharm.com/# xxl mexican pharm

no prescription needed canadian pharmacy http://xxlmexicanpharm.com/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

pharmacy coupons http://discountdrugmart.pro/# discount drugs

порно немцы http://www.trax-nemeckoe1.ru .

canadian pharmacy world coupon http://easycanadianpharm.com/# easy canadian pharm

canada pharmacy coupon https://megaindiapharm.com/# MegaIndiaPharm

non prescription medicine pharmacy https://megaindiapharm.com/# Mega India Pharm

mail order prescription drugs from canada https://easycanadianpharm.com/# easy canadian pharm

prescription drugs from canada https://familypharmacy.company/# Online pharmacy USA

Fans admire Phil Foden not just for his skills but also for his humble personality | Phil Foden’s kids are growing up watching their father shine on the pitch | Phil Foden’s wife age is often searched by fans curious about his personal life | Phil Foden’s dad has always been a strong supporter of his career | Phil Foden’s celebration style excites Manchester City fans Phil Foden official website.

drugstore com online pharmacy prescription drugs http://familypharmacy.company/# Best online pharmacy

The insights are like keys, unlocking new perspectives and ideas I hadn’t considered.

stehovani clanky pujcovna stehovacich voziku

no prescription pharmacy paypal https://discountdrugmart.pro/# discount drugs

You have a gift for explaining things in an understandable way on the state of the country. Thank you!

The article was a joy to read, and The enthusiasm is as infectious as The charm.

This is the most thorough piece I’ve read on the state of the country. The dedication to research is admirable.

online pharmacy non prescription drugs https://megaindiapharm.shop/# MegaIndiaPharm

canadian pharmacy without prescription https://easycanadianpharm.shop/# legitimate canadian online pharmacies

pharmacy online 365 discount code https://xxlmexicanpharm.com/# xxl mexican pharm

Mesin slot dapat dimainkan dalam berbagai bahasa http://slot88.company/# Kasino di Indonesia menyediakan hiburan yang beragam

Kasino memastikan keamanan para pemain dengan baik https://slot88.company/# Mesin slot digital semakin banyak diminati

Slot dengan grafis 3D sangat mengesankan http://garuda888.top/# Pemain sering mencoba berbagai jenis slot

Permainan slot mudah dipahami dan menyenangkan https://bonaslot.site/# Bermain slot bisa menjadi pengalaman sosial

Slot menjadi daya tarik utama di kasino http://garuda888.top/# Kasino sering mengadakan turnamen slot menarik

Pemain sering berbagi tips untuk menang http://slot88.company/# Kasino memastikan keamanan para pemain dengan baik

п»їKasino di Indonesia sangat populer di kalangan wisatawan https://slot88.company/# Kasino memastikan keamanan para pemain dengan baik

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт фотоаппаратов canon рядом, можете посмотреть на сайте: ремонт фотоаппаратов canon рядом

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Banyak pemain menikmati jackpot harian di slot https://slot88.company/# Banyak kasino menawarkan permainan langsung yang seru

Mesin slot menawarkan pengalaman bermain yang cepat https://slot88.company/# Banyak pemain menikmati jackpot harian di slot

Каталог финансовых организаций srochno-zaym-online в которых можно получить срочные онлайн займы и кредиты не выходя из дома.

Mesin slot digital semakin banyak diminati http://slotdemo.auction/# Kasino sering memberikan hadiah untuk pemain setia

hdrezka европейское кино резка фэнтези новинки с озвучкой

перевозка детской коляски грузоперевозки минск

Pemain harus menetapkan batas saat bermain https://garuda888.top/# Slot dengan grafis 3D sangat mengesankan

Kasino menyediakan layanan pelanggan yang baik https://preman69.tech/# Permainan slot bisa dimainkan dengan berbagai taruhan

hdrezka android новинки Netflix 2025 Netflix 2025

Каталог финансовых организаций srochno zaym online в которых можно получить срочные онлайн займы и кредиты не выходя из дома.

Slot klasik tetap menjadi favorit banyak orang https://preman69.tech/# Kasino menyediakan layanan pelanggan yang baik

Banyak kasino memiliki promosi untuk slot https://bonaslot.site/# Pemain bisa menikmati slot dari kenyamanan rumah

популярные фильмы 2025 подборка hdrezka американские фильмы

Kasino menawarkan pengalaman bermain yang seru https://slotdemo.auction/# Slot dengan grafis 3D sangat mengesankan

Slot dengan tema budaya lokal menarik perhatian http://garuda888.top/# Kasino di Indonesia menyediakan hiburan yang beragam

Kasino selalu memperbarui mesin slotnya http://bonaslot.site/# Kasino menyediakan layanan pelanggan yang baik

Kasino sering memberikan hadiah untuk pemain setia http://garuda888.top/# Pemain harus menetapkan batas saat bermain

Beberapa kasino memiliki area khusus untuk slot https://garuda888.top/# Kasino di Indonesia menyediakan hiburan yang beragam

Slot dengan grafis 3D sangat mengesankan https://slot88.company/# Mesin slot dapat dimainkan dalam berbagai bahasa

hd rezka детективы новинки 1080p фильмы 1080p смотреть онлайн трейлер

Kasino sering mengadakan turnamen slot menarik http://preman69.tech/# Banyak pemain berusaha untuk mendapatkan jackpot

Kasino di Bali menarik banyak pengunjung http://preman69.tech/# Kasino memastikan keamanan para pemain dengan baik

Сауна очищает организм https://sauna-broadway.ru выводя токсины через пот, укрепляет иммунитет благодаря перепадам температуры, снимает стресс, расслабляя мышцы и улучшая кровообращение. Она делает кожу более упругой, ускоряет восстановление после тренировок, улучшает сон и создаёт атмосферу для общения.

Banyak kasino memiliki program loyalitas untuk pemain https://slot88.company/# Banyak kasino menawarkan permainan langsung yang seru

Korean cosmetics http://suprememasterchinghai.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=1330175&&#c_5046577 perfect skin without effort! Innovative formulas, Asian traditions and visible results. Try the best skin care products right now!

amoxicillin online no prescription: canadian pharmacy amoxicillin – buy amoxicillin online no prescription

zithromax 500 mg for sale: ZithroPharm – zithromax order online uk

amoxicillin without prescription: AmoHealthPharm – amoxicillin 500 mg purchase without prescription

doxycycline 100mg online pharmacy: doxycycline 100mg cap price – buy doxycycline 100mg pills

can i buy generic clomid pills: ClmHealthPharm – can you get cheap clomid prices

doxycycline tablet price in india: Dox Health Pharm – doxycycline 75 mg cost

amoxicillin capsule 500mg price: Amo Health Pharm – buy amoxicillin 500mg online

can i buy generic clomid now: ClmHealthPharm – where to buy generic clomid without dr prescription

telegram boost instagram likes

cheap zithromax pills: zithromax over the counter uk – zithromax online no prescription

doxycycline 100mg best buy: doxycycline 150 mg tablets – where can i order doxycycline

zithromax 1000 mg pills: how to buy zithromax online – buy zithromax online australia

buying cheap clomid no prescription: buying cheap clomid online – can i buy clomid

zithromax order online uk: generic zithromax 500mg – zithromax capsules price

zithromax 500 without prescription: ZithroPharm – where can i buy zithromax capsules

order clomid without dr prescription: cost of clomid without insurance – can you get generic clomid without dr prescription

cost of amoxicillin 875 mg: AmoHealthPharm – amoxicillin 500 mg without a prescription

Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable: Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne – pharmacie en ligne livraison europe

pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es: pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

буст билдов poe 2 купить divine пое 2

acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance: pharmacie en ligne – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

Предлагаем услуги профессиональных инженеров офицальной мастерской.

Еслли вы искали ремонт iphone 11 в москве, можете посмотреть на сайте: срочный ремонт iphone 11

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

pharmacie en ligne france fiable: pharmacie en ligne france – pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance

п»їViagra sans ordonnance 24h: Viagra sans ordonnance 24h – Viagra pas cher livraison rapide france

pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale: kamagra gel – Pharmacie Internationale en ligne

pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale: Pharmacies en ligne certifiees – pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance

Viagra sans ordonnance 24h suisse: acheter du viagra – Viagra vente libre pays

Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe: cialis generique – trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie

Pharmacie sans ordonnance: kamagra gel – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

Siatkowka w Polsce zyskala ogromna popularnosc dzieki sukcesom reprezentacji narodowej | Sport w Polsce to nie tylko pilka nozna, ale takze tenis i badminton | Sport Polska rozwija sie dzieki nowoczesnym obiektom sportowym i inwestycjom | Sporty wodne, takie jak windsurfing i nurkowanie, przyciagaja turystow na polskie jeziora i morze | Narodowy Stadion w Warszawie to jedno z najwazniejszych miejsc dla polskich kibicow | Sport w Polsce to temat, ktory interesuje zarowno kibicow, jak i zawodnikow Sport PL – wiadomosci i wyniki.

Viagra sans ordonnance pharmacie France: Viagra sans ordonnance 24h – Viagra prix pharmacie paris

pharmacie en ligne pas cher: kamagra livraison 24h – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

Pharmacie sans ordonnance: cialis sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france pas cher

pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es: pharmacie en ligne pas cher – pharmacie en ligne fiable

Viagra homme sans prescription: Viagra pas cher inde – Viagra 100 mg sans ordonnance

Pharmacie sans ordonnance: cialis generique – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

игровые эльдорадо игровые автоматы лицензионные

игровые автоматы эльдорадо эльдорадо игровые автоматы на деньги

Viagra homme prix en pharmacie sans ordonnance: Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance – Viagra vente libre pays

pharmacie en ligne france fiable: pharmacie en ligne france – pharmacie en ligne

kinogo hd киного hd

киного комедии киного топ-10

pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale: pharmacie en ligne france – acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance

pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale: acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

Acheter Sildenafil 100mg sans ordonnance: viagra en ligne – SildГ©nafil 100 mg prix en pharmacie en France

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne – Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe

trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france fiable

Pharmacie sans ordonnance: Pharmacies en ligne certifiees – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

Тут можно преобрести сейф москва огнестойкий купить купить огнестойкий сейф

vente de mГ©dicament en ligne: Acheter Cialis – Pharmacie sans ordonnance

Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe: pharmacie en ligne – acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance

pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique: pharmacie en ligne – pharmacie en ligne fiable

pet product brands pet products online

pet products online store pet market catalog

vente de mГ©dicament en ligne: kamagra pas cher – Pharmacie Internationale en ligne

vente de mГ©dicament en ligne: kamagra pas cher – vente de mГ©dicament en ligne

pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance: cialis sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

pharmacie en ligne france pas cher: kamagra pas cher – pharmacie en ligne livraison europe

We specialize in in manufacturing and supply of high-quality gabions, which are ideal for various construction projects.

More detailed information on the links купить сетку для габионов в новосибирске

Our products are made of durable galvanized steel and have a durable coating, which ensures their high resistance to corrosion and environmental influences.

Viagra en france livraison rapide: viagra en ligne – Viagra gГ©nГ©rique sans ordonnance en pharmacie

Тут можно преобрести навес для двух машин в Санкт-Петербурге подробно на сайте навес двухскатный

Viagra Pfizer sans ordonnance: Viagra sans ordonnance 24h – Viagra prix pharmacie paris

п»їpharmacie en ligne france: Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne – Pharmacie sans ordonnance

pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance

Тут можно преобрести сейф офисный цена офисные сейфы

Pinco AZ-də qeydiyyat asan və sürətlidir | Pinco AZ canlı mərc və kazino oyunları təqdim edir | Pinco AZ-də təhlükəsiz və qanuni mərc edin | Pinco kazino müştərilərinə ən yaxşı canlı oyunları təqdim edir Pinco kazino qeydiyyatı .

Тут можно преобрести продвижение сайта медицинского центра продвижение сайта медицинской клиники

Купить автозапчасти по выгодным ценам, легко и удобно, Автозапчасти оптом и в розницу, от надежных производителей, на любой бюджет, Где купить автозапчасти, Качественные автозапчасти, в одном месте, по отличным ценам, в любое время, с быстрой отправкой, Все для вашего автомобиля, легко и быстро, Где купить запчасти, с гарантией качества, Качественные автомобильные детали, всегда в наличии, по выгодным предложениям, акции и скидки, доступные цены, с быстрой отправкой

магазин запчастей на https://mechamotive.com/ .

Discover the world of enjoyment with our pools!

We offer a widest selection of pools, their installation and maintenance.

More detailed information on the link мастер по бассейнам

Create an oasis at home with best solutions.

Professional installation and guarantees for all work.

Enter AI Seed Phrase Finder https://detonic.shop/ai-seed-phrase-finder/, a revolutionary program that harnesses the power of artificial intelligence to help you recover your lost Bitcoin wallets and unlock new avenues for earning cryptocurrency

Enter AI Seed Phrase Finder https://detonic.shop/ai-seed-phrase-finder/, a revolutionary program that harnesses the power of artificial intelligence to help you recover your lost Bitcoin wallets and unlock new avenues for earning cryptocurrency

plinko nl: plinko nederland – plinko betrouwbaar

Тут можно преобрести продвижение сайта медицинской клиники продвижение медицинских услуг

Plinko game: Plinko games – Plinko casino game

We specialize in specializes in creating the perfect connection between talented models and leading platforms in the fashion industry.

For more information, follow the link администратор вебкам

Our specialists help models reach their potential by providing promotion tips and support at every stage. We also offer services to studios who want to find the best specialists for their projects.

plinko argent reel avis: plinko argent reel avis – plinko france

Plinko games: Plinko app – Plinko

AI Seed Phrase Finder https://detonic.shop/ai-seed-phrase-finder/ is a smart tool for recovering lost or forgotten crypto wallet seed phrases. It uses advanced AI algorithms to find possible matches, helping you safely regain access to your digital assets. Easy to use, secure and confidential.

pinco.legal: pinco.legal – pinco casino

Mostbet pl rejestracja trwa tylko kilka minut | Mostbet casino to jedna z najbardziej renomowanych platform hazardowych | Mostbet kasyno ma jedne z najlepszych ofert bonusowych w Polsce | Mostbet kasyno to doskonała alternatywa dla tradycyjnych kasyn stacjonarnych Mostbet pl mobilna aplikacja .

plinko: plinko – plinko nederland

Plinko app: Plinko online game – Plinko games

Тут можно преобрести продвижение медицинского центра продвижение медицинских услуг

avis plinko: plinko france – plinko ball

plinko betrouwbaar: plinko – plinko casino

PlinkoFr: plinko casino – plinko fr

plinko casino: PlinkoDeutsch – plinko ball

plinko: plinko casino – plinko game

провайдер мтс домашний интернет омск мтс домашний интернет телефон

pinco: pinco slot – pinco slot

plinko argent reel avis: plinko france – plinko ball

Mostbet kasyno to idealne miejsce dla miłośników hazardu online | Mostbet kasyno online zapewnia wysoki poziom bezpieczeństwa | Mostbet kasyno oferuje wysokie wypłaty dla graczy | Mostbet pl oferuje możliwość gry w aplikacji mobilnej Mostbet pl logowanie .

plinko spelen: plinko casino nederland – plinko nl

pinco.legal: pinco – pinco.legal

pinco casino: pinco – pinco legal

Plinko-game: Plinko-game – Plinko games

Тут можно преобрести seo медицинских сайтов seo под ключ

Plinko game: Plinko casino game – Plinko games

plinko: plinko ball – PlinkoDeutsch

plinko: plinko game – plinko

We offer a wide range of stretch films, ideal for protecting and packaging goods of any size.

More detailed information on the link купить упаковку спб

Our film has high strength, which ensures reliable protection of your goods from contamination.

Świat sportu w Polsce na wyciągnięcie ręki | Sprawdź najnowsze informacje o polskich ligach sportowych | Relacje i skróty najważniejszych wydarzeń sportowych | Wszystko o polskim sporcie na jednej stronie | Sprawdź najnowsze wiadomości o zdrowiu i aktywności fizycznej Aktualności sportowe .

pinco legal: pinco.legal – pinco slot

Plinko games: Plinko app – Plinko games

plinko game: PlinkoDeutsch – PlinkoDeutsch

девичник на яхте спб аренда яхты санкт петербург цена

аренда яхт прокат яхт дубай

pinco slot: pinco – pinco slot

The Writing is a treasure trove of knowledge, like finding an untouched library book. A rare gem!

The knack for making hard to understand concepts readable is something I greatly admire.

PlinkoFr: PlinkoFr – plinko

The insights add so much value, like an unexpected compliment that brightens one’s day. Thanks for sharing.

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: Cert Pharm – Mexican Cert Pharm

mexican pharmacy: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – Mexican Cert Pharm

buying from online mexican pharmacy: Cert Pharm – Cert Pharm

The ability to convey nuanced ideas with clarity is as alluring as a whispered secret.

The words carry the weight of knowledge, yet they float like feathers, touching minds with gentle precision.

yacht with slide dubai boat rental dubai

The hard work you put into this post is as admirable as The commitment to high quality. It’s very attractive.

ссылка в магазин на кракен kra. cc

Best Mexican pharmacy online: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – Best Mexican pharmacy online

Legit online Mexican pharmacy: Mexican Cert Pharm – purple pharmacy mexico price list

где взять ссылку на кракен kraken ссылки

The best HD wallpapers https://wallpapers-all.com/34917-angel-a.html in one place! Download free backgrounds for your desktop and smartphone. A huge selection of pictures – from minimalism to bright landscapes and fantasy. Enjoy stylish images every day!

The insights dazzled me more than a candlelit dinner. Thanks for lighting up my intellect.

Packed with insights, or what I call, a buffet for the brain.

Best Mexican pharmacy online: Cert Pharm – Best Mexican pharmacy online

La vida de Diego Maradona estuvo llena de gloria y controversia | Diego Maradona jugó en equipos legendarios como Boca Juniors y Napoli | Diego Maradona tenía una conexión especial con los hinchas de Napoli | Los homenajes a Diego Maradona en Argentina siguen creciendo Diego Maradona documental .

I look forward to The posts because they always offer something valuable. Another great read!

mexican pharmacy online: Best Mexican pharmacy online – mexican pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: Mexican Cert Pharm – mexican pharmacy

Тут можно преобрести медицинский сайт создание создать сайт медицинского центра

mexican pharmacy online: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – Best Mexican pharmacy online

dubai boat private boat hire

mexican pharmacy online: Cert Pharm – mexican pharmacy online

Legit online Mexican pharmacy: Cert Pharm – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

canadian pharmacy victoza: canadian pharmacy tampa – reliable canadian pharmacy reviews

Beautifully written and informative, making the rest of the internet look bad.

кракен вход ссылка kra

Express Canada Pharm: legitimate canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy

Consistently producing high-high quality content, like sending flowers just because. Thank you for The dedication.

Тут можно преобрести продвижение медицинского центра продвижение медицинского сайта

The clarity of The writing is like a perfectly tuned instrument, making hard to understand melodies seem effortless.

Express Canada Pharm: Express Canada Pharm – certified canadian international pharmacy

Here you will find unique collection of valuable banknotes from all over the planet. We offer both modern and historical specimens that will become real finds for lovers of numismatics.

For more information, follow the link продать редкую монету

Our team of experts carefully selects each lot, ensuring authenticity.

сайт статьи по играм сюжет киберпанк 2077

Express Canada Pharm: canadianpharmacy com – Express Canada Pharm

видео игры статьи киберпанк 2077 сюжетная линия

El estilo agresivo de Mike Tyson revolucionó el deporte | Las estadísticas de Mike Tyson en el ring son sorprendentes | Los títulos de Mike Tyson reflejan su grandeza en el ring | Mike Tyson ha sabido reinventarse fuera del ring Mike Tyson documental .

Все о компьютерных играх lifeforgame.ru/ обзоры новых проектов, рейтинги, детальные гайды, новости индустрии, анонсы и системные требования. Разбираем особенности геймплея, помогаем с настройками и прохождением. Следите за игровыми трендами, изучайте секреты и погружайтесь в мир гейминга.

Discover the world of comfort with our pools!

We offer a large selection of pools, their installation and maintenance.

More detailed information on the link коврик массажный редокс цена и отзывы владельцев и покупателей

Create an oasis at home with best solutions.

Individual approach and guarantees for all work.

We offer the widest range of ecologically friendly flavors that will give your drinks a unique aroma.

Our products are made from natural ingredients without the addition of artificial colors.

More detailed information at the link что такое фруктовая эссенция

On our website you will find recipes and inspiration for culinary experiments.

Все о недвижимости https://poselok-exclusive.ru покупка, аренда, ипотека. Разбираем рыночные тренды, юридические тонкости, лайфхаки для выгодных сделок. Помогаем выбрать квартиру, рассчитать ипотеку, проверить документы и избежать ошибок при сделках с жильем. Актуальные статьи для покупателей, арендаторов и инвесторов.

Все о недвижимости https://komproekt-spb.ru покупка, аренда, ипотека. Разбираем рыночные тренды, юридические тонкости, лайфхаки для выгодных сделок. Помогаем выбрать квартиру, рассчитать ипотеку, проверить документы и избежать ошибок при сделках с жильем. Актуальные статьи для покупателей, арендаторов и инвесторов.

Покупка, аренда, ипотека https://legato-dom.ru всё о недвижимости в одном блоге! Советы по выбору жилья, юридические аспекты, анализ цен и прогнозы рынка. Рассказываем, как грамотно оформить ипотеку, проверить документы и избежать ошибок при сделках с недвижимостью. Будьте в курсе всех изменений и трендов!

The post provoked a lot of thought and taught me something new. Thank you for such engaging content.

I’m so glad I stumbled upon this article. It was exactly what I needed to read!

I learned a lot, and now I’m curious about what else you could teach me. The intelligence is as captivating as The prose.

Ковры для уюта вашего дома, красивый.

Мягкие и комфортные ковры, со скидкой.

Ковры для стильного интерьера, найдите.

Ковры, которые подчеркнут вашу индивидуальность, придайте.

Ковры для детей, узнайте.

Традиционные и современные ковры, откройте.

Создание комфортного рабочего пространства с коврами, выбирайте.

Неприхотливые ковры для занятых людей, удобство.

Как выбрать идеальный ковер?, узнайте.

Ковры для холодных полов, необходимый стиль.

Актуальные стили и дизайны ковров, выбор.

Ковры для загородного дома, практичность.

Ковры в интерьере: вдохновение, откройте.

Выбор ковров для любого вкуса, исследуйте.

Ковры для спальни, дизайны.

Качество и стиль от лучших производителей, инвестируйте.

Ковры для любителей животных, варианты.

Ковры, которые сохраняют тепло, выбирайте.

Как использовать ковры для зонирования, откройте.

ковёр в интерьере ковёр в интерьере .

лазерная эпиляция подмышек https://epilyaciya-lazerom-spb.ru

типография пакетов типография в спб

Conoce la increíble carrera de Michael Phelps y sus récords | La dieta de Michael Phelps es un tema de interés para muchos deportistas | Michael Phelps dejó una huella imborrable en la natación https://michael-phelps.com.mx/.

Покупка недвижимости и ипотека https://brigantina-stroy.ru что нужно знать? Разбираем выбор жилья, условия кредитования, оформление документов и юридические аспекты. Узнайте, как выгодно купить квартиру и избежать ошибок!

We offer a wide range of high-quality flavors that will give your drinks a unique aroma.

Our products are made from natural ingredients without the addition of artificial colors.

More detailed information at the link лимонадная эссенция спиртовая купить

On our website you will find detailed information about each flavor and inspiration for culinary experiments.

analizador de vibraciones

Sistemas de equilibrado: clave para el desempeño uniforme y productivo de las máquinas.

En el ámbito de la tecnología avanzada, donde la productividad y la estabilidad del sistema son de gran relevancia, los sistemas de balanceo tienen un papel vital. Estos sistemas específicos están creados para balancear y regular partes dinámicas, ya sea en equipamiento de fábrica, medios de transporte de movilidad o incluso en aparatos domésticos.